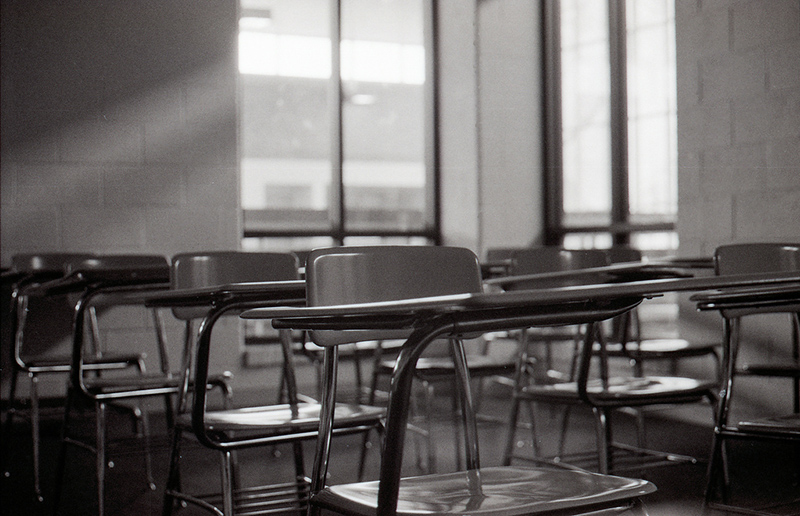

With millions of students missing 15-plus days of school each year, a new report suggests increased tracking of chronic student absenteeism. (Don Harder / Flickr)

With millions of students missing 15-plus days of school each year, a new report suggests increased tracking of chronic student absenteeism. (Don Harder / Flickr)

As states work to revamp their individual education policy models under new federal mandates, a new report suggests putting a focus on how often students are actually showing up to their classrooms.

Each state’s accountability plan under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) – the federal law replacing No Child Left Behind (NCLB) at the beginning of next school year – must include four accountability measures, along with one non-academic indicator tracking either school quality or student success.

According to a report from The Hamilton Project, the best bet for that “fifth indicator” may be tracking chronic student absenteeism:

“State policy should, through its accountability system, encourage schools to ensure every child is in school every day and learning. By adopting chronic absenteeism as the fifth indicator, states will hold schools accountable to this goal.”

To be “chronically absent,” a student must miss at least 15 total days over the course of a standard school year. The Office of Civil Rights Data Collection estimates about one in seven K-12 students fit that definition during the 2013-14 school year.

That equates to roughly 98 million class days lost.

The chronic absenteeism metric allows for differentiation between schools and includes comparable and statewide attributes – requirements for any fifth indicator under ESSA – but the study also argues the vast majority of schools have significant room for improvement.

“Only 8.5 percent of regular public and charter schools nationwide reported no students who were chronically absent,” the report states, referring to OCR data from the 2013-14 school year. “Put another way, more than 90 percent of schools can improve their rates of chronic absenteeism.”

An abundance of available research compiled in recent years puts into perspective how important just showing up to school can be for a child at any grade level. Connections have been made between kindergartners missing school and depressed achievement levels; sixth graders attending less than 80 percent of class days and failing to move on to high school; and chronically absent high schoolers dropping out at substantially higher rates than their peers.

The Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) has also claimed a high attendance rate is more predictive of student graduation than standardized test scores.

And the negative effects brought about by chronic absenteeism do not plateau after 15 missed school days. The report states that as students move further and further beyond that threshold, they perform worse on standardized tests than those students deemed only “moderately chronically absent.”

Though it doesn’t specifically report on chronic absenteeism, ISBE does track chronic truancy – students missing nine or more school days in a given year without a valid excuse.

Statewide, the number of chronic truants has hovered between 9 and 10 percent of students over the past five years, according to data from the latest Illinois Report Card. Within Chicago Public Schools, that percentage is more than three times higher.

National distribution of chronic absenteeism. (The Hamilton Project)

For as many problems chronic absence and truancy create, there seems to be equally as many root causes – from health or family issues keeping kids from class, to harassment and safety concerns preventing them from wanting to go to class.

"Although there’s a myriad reasons why they’re truant, the end result oftentimes (stems from) a disconnection from all institutions," Brighton Park Neighborhood Council Executive Director Patrick Brosnan said, "so it really increases the number of disconnected youth, and in communities where there’s high numbers of disconnected youth, there’s also real high levels of violence.”

BPNC works to connect hundreds of students and parents with needed resources relating to education, violence prevention, economic development and health care around Brighton Park. Much of that work also has to do with limiting truancy at schools.

The council has developed a violence prevention strategy and works to connect case managers with students missing class. While there has been success, Brosnan believes there is still substantial room for expansion.

His group, for example, works specifically with students who have been referred to them by schools. But there is not yet "street-level capacity" in place for students who have stopped attending class altogether.

"Our universe of support programs are really focused on kids that have one foot out the door, not both," he said. "And what’s really needed is services for those kids."

Getting hold of specific absentee figures had also been difficult prior to ESSA. Under the new law, schools are now required to report chronic absence, suspension and expulsion rates to the Civil Rights Data Collection.

But previously under NCLB, schools and districts would often look at average daily attendance numbers, a metric which can obfuscate just how often students are actually at school, according to Marty Blank, president of the Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Educational Leadership.

“You could have schools with 90 percent or 92 percent attendance, but if the children who are absent every day are different children, you really have a higher chronic absence rate,” he said.

Many states, Illinois among them, remain in the process of drafting their individual ESSA accountability plans that will go into effect at the start of the 2017-18 school year. ISBE Director of Media & External Communications Jackie Matthews said the board is now working on its second draft based on feedback collected from a pair of statewide listening tours and hundreds of comments submitted online.

In an email, she added: “Chronic absenteeism was included in the first draft of the ESSA State Plan as a possible indicator of school quality.”

Last year, the state also convened a committee of education officials and parent organization leaders to study chronic absenteeism and draft prevention strategies. That group is expected to release an annual report to ISBE and the General Assembly next month.

(Office For Civil Rights Data Collection)

A 2012 investigative study by the Chicago Tribune revealed 32,000 CPS students, including large numbers of African-American students and kindergartners, had missed at least four weeks of school during the 2010-11 school year.

While chronically absent students are more likely to continue missing class days as they progress from grade to grade, the effects are reversible. A 2012 study of Baltimore students found kindergartners who started off chronically absent were able to close the achievement gap with their peers in later grades.

But students can also backslide during their academic careers from one issue causing a prolonged absence to another.

“A kid might be in the second grade and you’ll solve a problem and their attendance will get better, and then something will happen in the fourth or fifth grade that will again create a dilemma,” Blank said. “So one needs to create a sustained capacity to support the children and support their families so they are attending schools on a very consistent basis.”

To do that, Blank suggests getting teachers more actively involved in their students’ lives – such as parent/teacher in-home visits – and matching schools with community-based organizations like BPNC that can provide assets and resources to keep kids coming to class.

He believes the chronic absenteeism metric can also work as a canary in a coal mine due to its potential to root out other systemic issues that aren't as readily apparent.

“If kids are missing schools because they have high rates of asthma, that means you’ve got to talk about what the health system is doing,” he said. “If kids are missing school because moms have mental health issues and they keep their kids home because they want somebody around, then you have to have the mental health system engaged.”

Follow Matt Masterson on Twitter: @ByMattMasterson

Related stories:

Illinois Report Card Shows Student Achievement Stable, in Need of Improvements

Illinois Report Card Shows Student Achievement Stable, in Need of Improvements

Oct. 31: The Illinois State Board of Education on Monday released its annual Report Card – a snapshot of accountability and achievement figures from students, schools and administrators across the state.

CPS Data Show Minority Students More Likely to be Suspended, Expelled

CPS Data Show Minority Students More Likely to be Suspended, Expelled

Sept. 22: More than 96 percent of district suspensions and 99 percent of expulsions affected minority students last school year.

CPS Progress Report Highlights Gains in On-Track, Dropout Rates

CPS Progress Report Highlights Gains in On-Track, Dropout Rates

Sept. 7: Students at Chicago Public Schools have steadily improved their attendance and on-track-to-graduate rates while trimming back their annual dropout rate over the past five years, according to a new district progress report.