The Chicago City Council on Wednesday overhauled the city’s most prominent tool to build affordable housing, voting to require developers that get special permission from the city or a subsidy to build more units for low- and moderate-income Chicagoans and pay higher fees.

The 42-8 vote was a victory for Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who promised during the campaign to overhaul the city’s laws to reduce the affordable housing gap of nearly 120,000 homes in Chicago. However, the ordinance approved by the City Council does not go as far as proposals Lightfoot endorsed during the 2019 mayoral campaign.

Lightfoot said the revised law is designed to address Chicago's "systematic patterns of segregation."

"The unfortunate reality is that our city has a dark history of racial segregation," Lightfoot said. "It is up to us to address its modern-day manifestations."

Once the new law takes effect Oct. 1, it would give developers incentives to build in parts of the city where there is little affordable housing or where longtime residents are vulnerable to displacement.

The vote came at the first City Council meeting to take place in person since February 2020. While 28 aldermen returned to the Council Chambers, 22 participated remotely via zoom.

The measure split the six aldermen who are members of the Chicago chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, with Ald. Daniel La Spata (1st Ward), Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th Ward) and Ald. Andre Vasquez (40th Ward) voting in favor, while Ald. Jeanette Taylor (20th Ward), Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez (25th Ward) and Ald. Rossana Rodriguez Sanchez (33rd Ward) voted no.

Along with Sigcho-Lopez and Rodriguez Sanchez, Ald. Maria Hadden (49th Ward) also voted against the measure because it does not do enough to make sure very low-income Chicagoans could afford the units it creates and does not require developers to build family size units.

Four of the City Council’s most conservative members — Alds. Brian Hopkins (2nd Ward); Ald. Nicholas Sposato (38th Ward), Ald. Anthony Napolitano (41st Ward) and Ald. Brendan Reilly (42nd Ward) — also voted against the measure.

Housing Committee Chair Ald. Harry Osterman (48th Ward) said the revised measure would not solve the city’s entire affordable housing crisis but represented a middle ground and would help Chicagoans as the city recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic to move forward.

“We have to do much more,” particularly on the South and West sides, Osterman said.

The new law is the fruits of the labor of a Lightfoot-formed task force which urged city officials in September to overhaul the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance approved 13 years ago to ensure it created homes and apartments that low- and moderate-income Black and Latino Chicagoans could afford.

The city’s affordable housing ordinance will continue to apply to any development of 10 or more units that needs special approval by city officials, is on city-owned land or is subsidized by taxpayer funds. But developers will now have to set aside 20% of units for low- and moderate-income Chicagoans, up from the current requirement of 10% in most Chicago neighborhoods.

The revised measure targets areas of the city that need more affordable housing, rather than focusing on individual projects, said Daniel Kay Hertz, policy director for the Department of Housing.

The city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance created just 1,049 homes in 13 years — barely a dent in the city’s affordable housing gap of nearly 120,000 homes, which has put “swaths of the city out of reach of low-income and working-class Chicagoans,” according to the task force’s report.

The 20-member task force determined that a more robust affordable housing ordinance could help stop the “massive exodus of Black Chicagoans from the South and West sides” and the displacement of Latino families from the Northwest Side.

Under the current ordinance, units considered affordable are designed for households earning approximately 60% of area median income. Those units are unaffordable for most Black and Latino Chicagoans, according to the task force report.

The median household income of Black Chicagoans is $27,713, while the median household income of Latino Chicagoans is $40,700, according to an analysis of American Community Survey data by the Metropolitan Planning Council for the task force. That means more than six in 10 Black Chicago households and more than five in 10 Latino Chicago households could not afford a rental unit set aside as affordable under the current law.

The task force’s top recommendation called for the city’s ordinance to be changed to require units be set aside for low- and moderate-income residents earning significantly less than 60% of area median income or $53,460 for a family of four, on average, according to the report.

To achieve that goal, developers will now be required to set aside one-third of the affordable units for households earning no more than 50% of area median income or $44,550 for a family of four, according to the proposal. One-sixth of the units must be affordable to households that earn no more than 40% of area median income, according to the new law.

Developers who agree to set aside more units for households earning no more than 40% of area median income only have to set aside 13% of their new units as affordable, while those who agree to set aside more units for earning no more than 40% of area median income only have to set aside 10% of their units as affordable, according to the new law.

Other incentives will encourage developers to build family size units by allowing those who build three- and four-bedroom units to build fewer units, another major recommendation of the task force to build larger units. In addition, any off-site units must have at least two bedrooms.

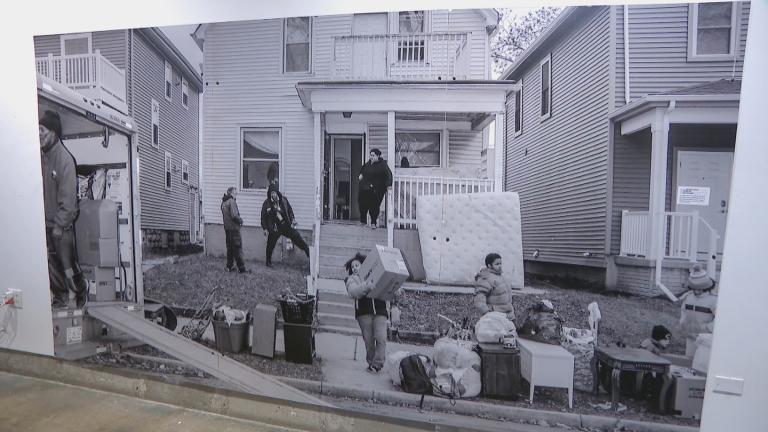

(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

Less than 5% of the units created by the Affordable Requirements Ordinance since 2007 included three bedrooms, making them unsuitable for most Black families, which have an average of 2.7 members, as well as most Latino families, which have an average of 3.7 members, according to the task force report.

Projects near bus and rail lines that trigger the ordinance would also be encouraged to eliminate parking spaces.

At least a quarter of the required affordable units must be built as part of the larger development, while another quarter could be built off-site in any part of the city, except for developments in areas in which the city determines longtime residents are at risk of being displaced from their homes, according to the proposal.

Developers would still be allowed to opt out of building new affordable units by paying a fee under the revised proposal, but those fees would rise significantly for projects that are in Chicago’s wealthiest neighborhoods, like downtown, from $175,000 to approximately $375,000, according to the proposal.

However, the measure approved Wednesday does nothing to end the unwritten rule of aldermanic prerogative, which has been used by aldermen from primarily white wards to block affordable housing from being built and has fueled segregation in Chicago.

While Lightfoot has vowed to prevent aldermen from exercising that power to block affordable housing, she has yet to take action.

In other action Wednesday, aldermen unanimously voted to approve a revised ban on pet stores from selling dogs, cats and rabbits at a profit in an effort to close a loophole in a nearly seven-year-old city law.

Aldermen also approved a measure to loosen the rules governing the operation of home businesses in an effort to help Chicagoans trying to expand their side hustles, especially female, Black and Latino Chicagoans.

Businesses are now also required to give employees paid time off to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Firms that violate the measure could face fines ranging from $1,000 to $5,000.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]