They closed some 44 years ago, but Chicago's Union Stockyards profoundly shaped the development of the city and the modern world. At its peak, more than 18 million livestock were slaughtered annually and, amazingly, the grim mechanization of death attracted thousands upon thousands of tourists—including European royalty.

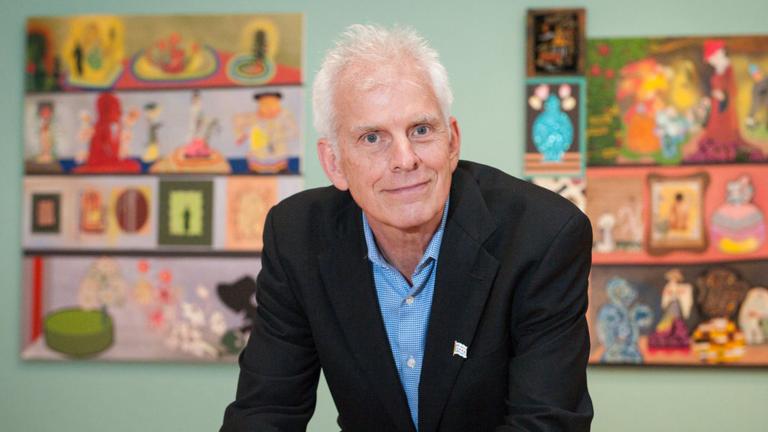

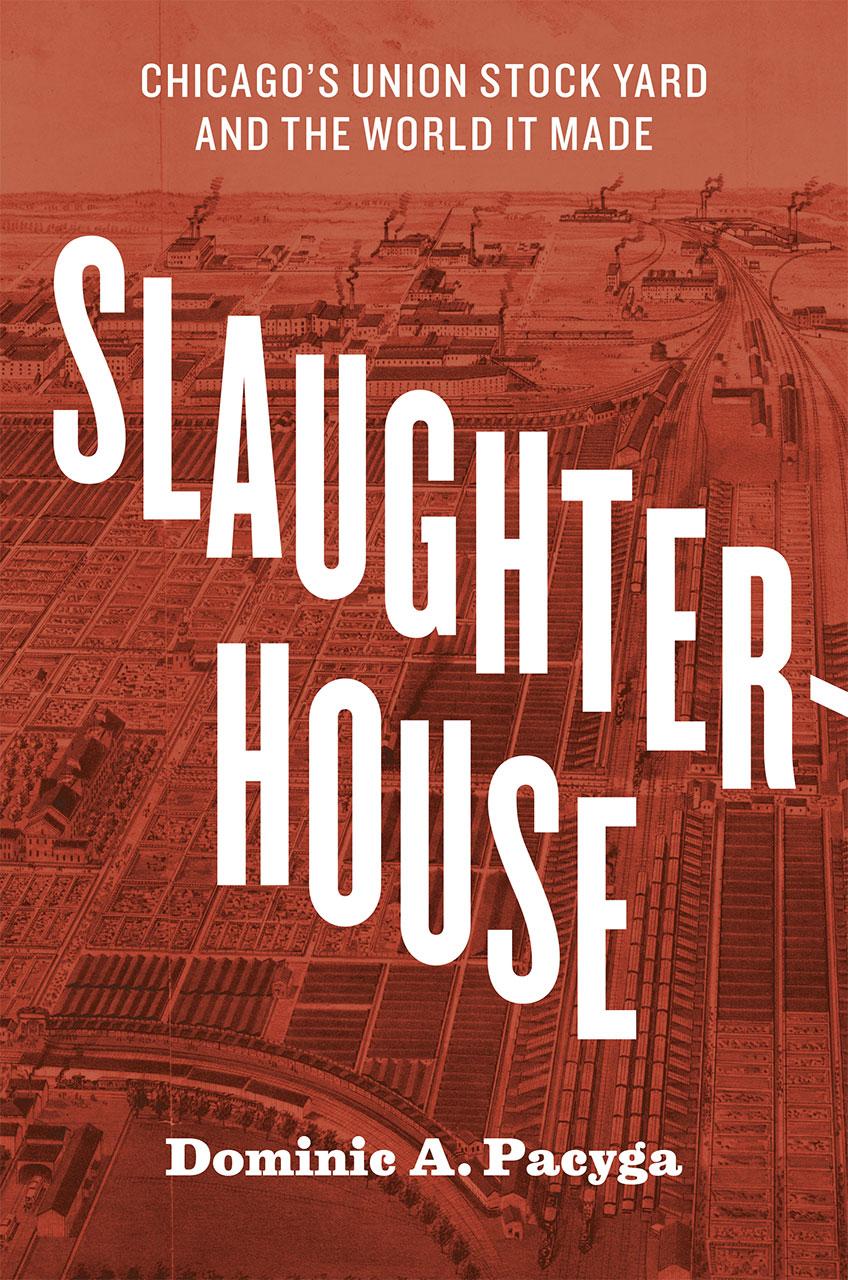

Dominic Pacyga, a professor of history at Columbia College Chicago and a former stockyard worker, tells the story in his new book "Slaughterhouse: Chicago’s Union Stock Yard and the World it Made."

Pacyga joins us to discuss the industry that forever changed the city and once earned Chicago the nickname "hog butcher for the world."

Read an exerpt from "Slaughterhouse":

Introduction

The Union Stock Yard and Packingtown provided an economic and symbolic base for the neighborhoods and the city that grew around it. This place drew men and women, both native born and immigrants, from around the country and the world to find their future in the maze of livestock pens and giant packinghouses. To be from Back of the Yards, Canaryville, Bridgeport, or McKinley Park, the neighborhoods surrounding the old stockyards, still implies a certain social class and even worldview. The American working class was formed by such places all across the nation’s landscape. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these places introduced Americans to the modern—that is, the new industrial economy that emerged after the Civil War. Over the years, the stockyards continued to define and redefine what was modern and what was not modern for many Chicagoans. It provided both spectacle and innovation to a public that saw its very life being transformed by industrialism.

The Union Stock Yard and Packingtown provided an economic and symbolic base for the neighborhoods and the city that grew around it. This place drew men and women, both native born and immigrants, from around the country and the world to find their future in the maze of livestock pens and giant packinghouses. To be from Back of the Yards, Canaryville, Bridgeport, or McKinley Park, the neighborhoods surrounding the old stockyards, still implies a certain social class and even worldview. The American working class was formed by such places all across the nation’s landscape. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these places introduced Americans to the modern—that is, the new industrial economy that emerged after the Civil War. Over the years, the stockyards continued to define and redefine what was modern and what was not modern for many Chicagoans. It provided both spectacle and innovation to a public that saw its very life being transformed by industrialism.

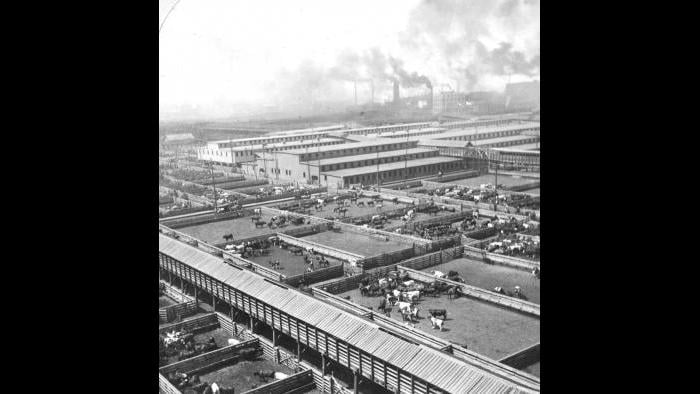

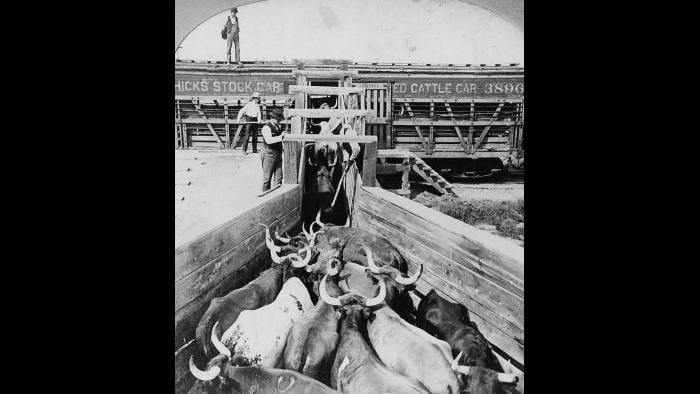

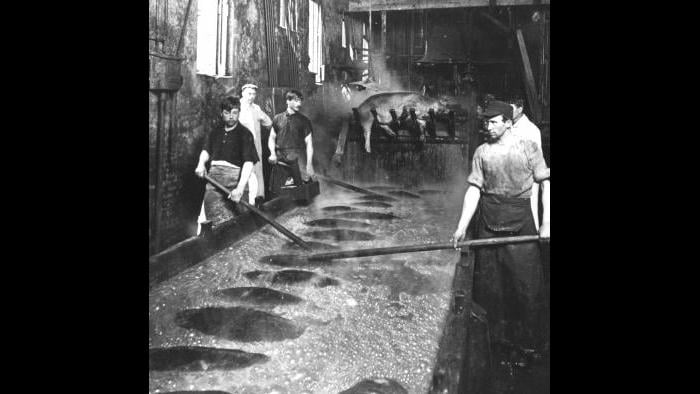

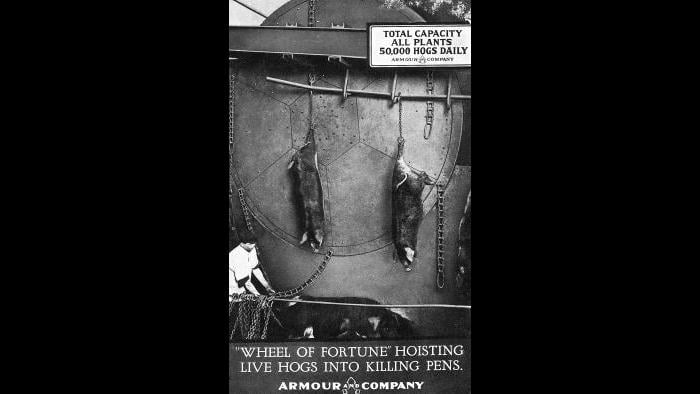

When they hear the word “stockyards,” most Chicagoans born before about 1955 recall the smell emanating from that one square mile of the city’s South Side on a warm summer day. For years after the packers disappeared the stench seemed to linger. It was not a ghostly stink: the huge fertilizer plants owned by Darling and Company on both Ashland Avenue and on Racine Avenue continued to operate well after the cattle, hogs, and sheep had left. In the “Square Mile” at its prime stood numerous packinghouses, ringed by railroad lines adjacent to the tens of thousands of animal pens of the Union Stock Yard. Train tracks encircled the stockyard and delivered a constant flow of livestock to the Chicago market and then the world. Railroad docks stood ready to unload the massive quantities of animals, to be sold to packers daily in the huge fairground. During World War One—the height of its history—some fifty thousand people found employment in the stockyards and adjacent Packingtown. Tens of thousands of cattle, calves, hogs, and sheep changed hands every day in the market. Afterward, about one-third reboarded trains and headed to slaughterhouses further east. The rest met their fate in Packingtown.

Unloaded on the docks that could handle hundreds of livestock railcars at a time, the creatures were counted and accounted for, then driven to the sale pens. Once sold, employees weighed and then drove them to the abattoirs that sent them off as meat products from Armour’s, Swift’s, Morris’s, Wilson’s, or any number of smaller independent plants. Thanks to the by-products industry, various animal parts became combs, buttons, lard, fertilizer, or even pharmaceuticals as the packers used everything, as the cliché said, but the squeal of the vanquished hog.

By World War One, Chicago’s meatpacking products were known, for better or worse, throughout the world. As the river of cattle, hogs, sheep, and horses flowed into the Union Stock Yard, it seemed that Chicago would never lose its title as packing industry leader, but the seeds of its decline were sown as the practice of direct buying and the emergence of the truck began to further transform the business. By 1930, technological change and new entrepreneurial systems ended the glory days of meatpacking in Chicago. While the city’s meat industry continued to perform admirably during World War Two, as the war came to a close it continued to fade.

In 1952, Wilson and Company opened an up-to- date packing plant in Kansas City; two years later, it announced the closing of its giant Chicago operations. By the end of the decade, Swift and Armour also decided to leave the Chicago Stockyards. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company updated its facilities and celebrated its one hundredth anniversary, announcing that, while the big packers had left, it would survive and thrive. Charles S. Potter, the president of the USY&T Company, proclaimed, “Chicago will not be only the largest livestock market in the world, but also the most up to date in facilities for both buyer and seller.” Famous last words: less than six years after celebrating its centennial, the Union Stock Yard closed forever. The new McCormick Place and other venues eclipsed the nearby International Amphitheater as a target destination for trade shows, political conventions, and rock concerts. The Square Mile was a shadow of its former self.

It was not, however, the end of “the yards.” Today, the Stockyard Industrial Park is one of the most successful industrial sites in the city, to some degree taking up where the old Union Stock Yard left off. Many different industries have joined the few remaining meat purveyors and the two slaughterhouses located at Forty-First and Ashland Avenue and Thirty-Eighth and Halsted Street. Park Packing still slaughters hogs within the Square Mile, and Chiappetti Packing butchers lambs and sheep just outside the formal boundaries of the yards. New industries, such as Testa Produce and The Plant, a food business incubator, have arrived and are developing new green technologies. Once again, tourist groups visit some of the plants now housing a vast array of industries. Again, the Southwest Side of Chicago is on the cutting edge of industrial change.

Reprinted with permission from Slaughterhouse: Chicago's Union Stock Yard and the World It Made by Dominic A. Pacyga published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2015 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Related:

Chicago's Union Stockyards: 40 Years Since Closing

Chicago's Union Stockyards: 40 Years Since Closing

In 2011, "Chicago Tonight" reported on the 40-year anniversary of the closing of Chicago's Union Stockyards. Watch footage and interviews taken by a local filmmaker on the last day the yards were in operation. We've also got some great historic photos of the stockyard.