Cyclists of color in Chicago get a disproportionate number of tickets from police, according to reports by the Chicago Tribune. But a new study finds that it’s not just about biking while Black or Latino, but also where those cyclists are. Bike advocates hope a new city initiative can help address the problem, but say it’s not just about infrastructure.

That initiative, announced by the Chicago Department of Transportation in late September, is what the city calls the largest-ever expansion of bike lanes in Chicago. The two-year, 100- mile installation and upgrade effort will focus particularly on West and South Side neighborhoods that haven’t had the kind of bike infrastructure other parts of the city enjoy.

“I’m excited about the expansion, but it has to be done very carefully,” said Kate Lowe, associate professor of urban planning and policy at UIC.

Lowe says some residents associate bike lanes with gentrification and displacement, so community engagement is key – and she wants planners to think beyond just painted lanes.

“One thing a lot of bike advocates would like to see more of is protected bike lanes, and that’s also relevant to this intersection of policing and bicycle infrastructure,” Lowe said.

That intersection was the focus of a new study authored by Jesus Barajas of UC Davis. It found the same thing as earlier investigations. “More tickets in Black and brown neighborhoods. There were six tickets per 1,000 in majority Black neighborhoods and .7 per 1,000 in majority white neighborhoods,” Barajas said.

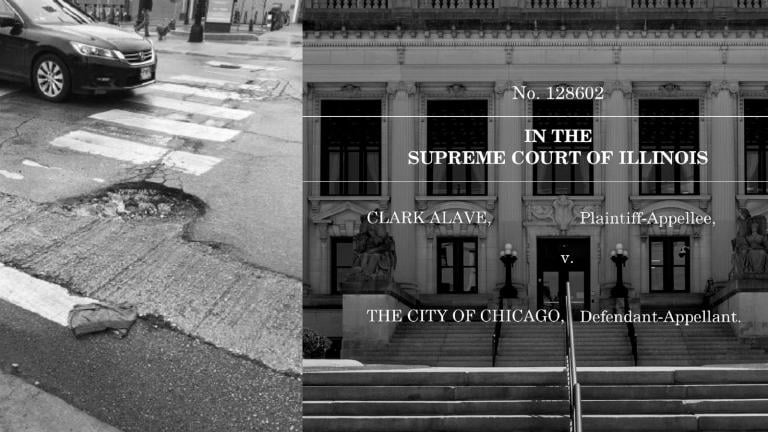

But the study went a step further to look at the infrastructure in the areas where tickets were issued. It found that bike lanes were disproportionately missing from majority Black and Latino neighborhoods.

“When people are riding on busy streets, they may not feel safe from traffic that’s there, so they’ll go on the sidewalk, and that’s where you’re going to get a ticket,” Barajas said. “When there was any kind of bike infrastructure on those arterials, the rate of ticketing went down – in some cases by up to 75%.”

The study also found no relationship between the number of tickets issued and the number of bike crashes, particularly serious crashes.

“What we suspect – and I would imagine any advocate or any person of color in the city of Chicago would confirm this with their own experience – (was) that this was really a pretext for other kinds of activities for the police. It wasn’t tied to safety, it was tied to other reasons,” Barajas said.

The study was part of the nonprofit Equiticity‘s Mobility Justice in Chicago project. Lowe, who serves on Equiticity’s research team, says the results point to over-policing in communities of color.

“There will be discriminatory policing that needs to change, even with bike lanes, but bike lanes can partially mitigate the impacts,” Lowe said.

And as bike lanes expand, Equiticity’s calling on Chicago not to heavily rely on police enforcement as part of its “Vision Zero” strategy to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries. Barajas says that’s a conversation happening nationwide, “How we can still get to that place of zero traffic deaths without automatically relying on police enforcement.”

The Chicago Police Department did not immediately respond to a request for comment.