Last week marked the 50th anniversary of the assassination of civil rights giant Martin Luther King, Jr.

A week after King’s death, President Lyndon Johnson signed what some called a monument to his work: the Fair Housing Act of 1968. There were hopes that it would mean better access to the American dream for African-Americans. But 50 years later, some say the landmark legislation didn’t go far enough.

![]()

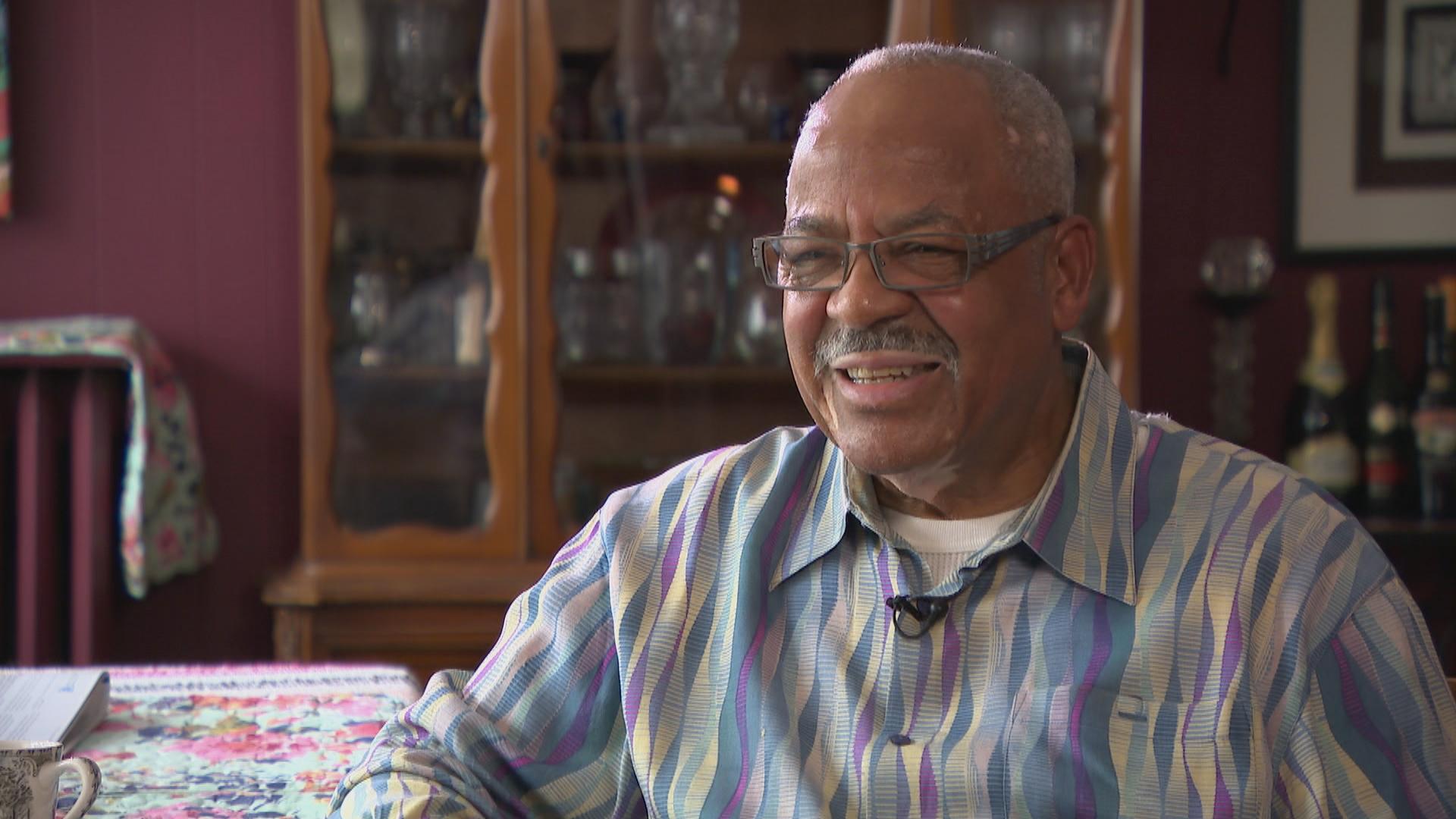

At 79-years old, Frank Williams can rattle off an address from 50 years ago, as if he were just there today.

It comes from years of working in the real estate industry.

He earned his license in 1966.

The same year of the Chicago Freedom Movement, when the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Chicago to further the fight for fair housing.

Williams was one of very few blacks in the industry at the time.

“The denial of ownership, the denial of loans, and then naturally the steering, the segregating. … I said, I want to make a difference … I’ve got to get a seat at the table to start making a difference,” Williams said.

Two years later – and one week after the assassination of King – President Lyndon Johnson signed the historic Fair Housing Act into law.

The bill outlawed racial discrimination in housing sales and rentals.

“I was so excited!” said Williams. “I just thought … this bill had passed, there’s going to be masterful change, everything’s going to be all right. Ha!”

But the law’s passage didn’t change discriminatory housing practices.

“There was still the redlining,” Williams said. “The institutions really had red lines drawn around communities at that time, which said even if we make loans, there’s going to be a different kind of loan being made within that community.”

Even the National Association of Realtors acknowledges that it was on the wrong side of history in 1968.

At the time, it was known as the National Association of Real Estate Boards, or NAREB.

“The rationale back then was, ‘We want to stop government from forcing me to sell to someone I don’t want to sell to,’” said Fred Underwood at the National Association of Realtors. “That was what ‘forced housing’ was.”

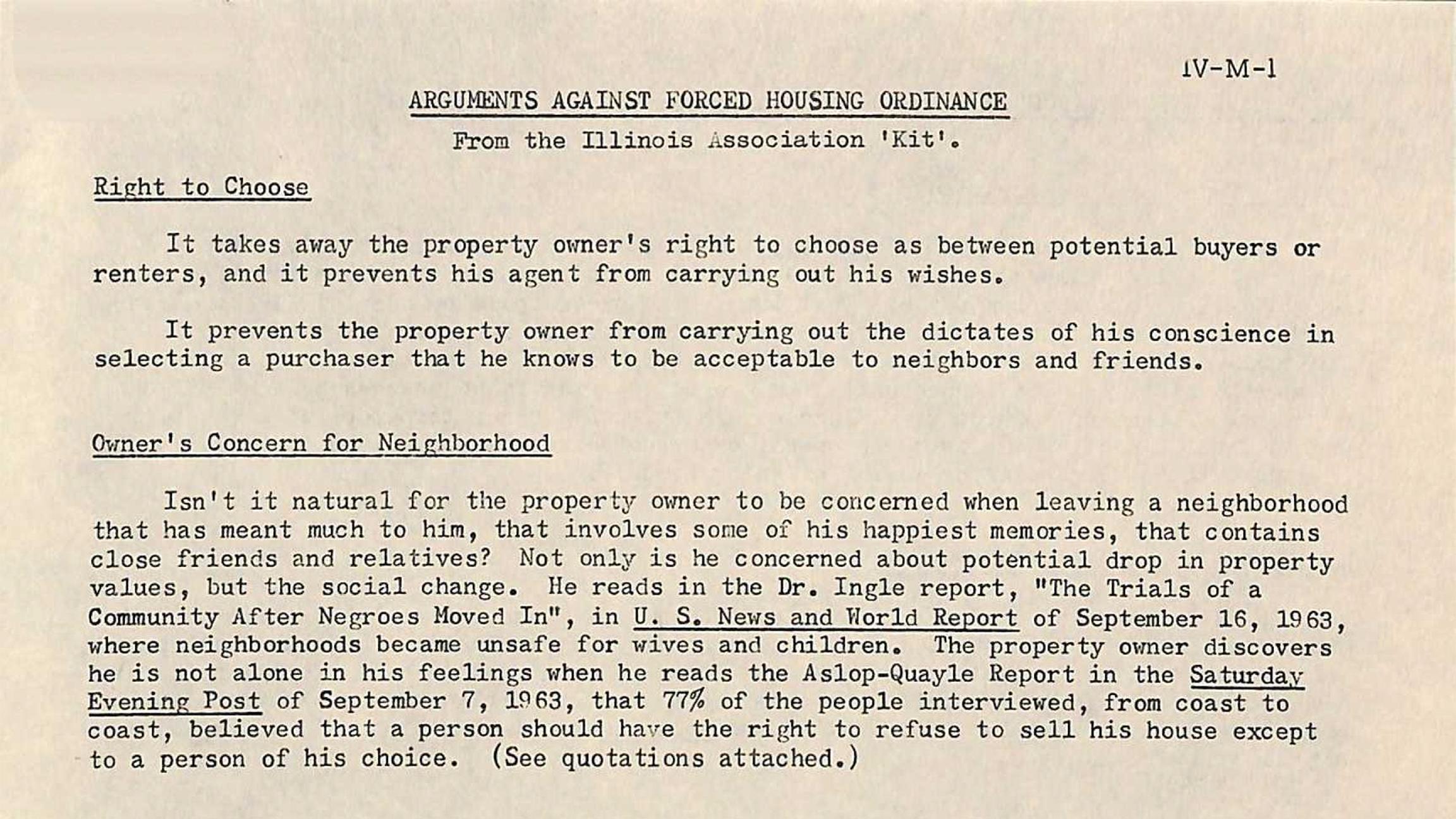

Opponents of “fair” housing referred to it as “forced” housing – even providing kits to real estate agents to help them avoid integrating neighborhoods.

The Property Owners’ Bill of Rights approved in 1963 by the association argued that “the individual American property owner, regardless of race, color or creed” must be allowed to, among other things, “determine the acceptability and desirability of any prospective buyer or tenant of his property.”

Among the Chicagoans who fought for fair and open housing was Rev. Jesse Jackson, who recalls the resistance blacks met when trying to buy or rent in other neighborhoods.

“The insurance companies would not lend there, the banks would not they were redlining,” Jackson said. “So really the bankers and the insurance companies were the real culprits, but the kids on the street were throwing rocks.”

Williams says his office FJ Williams Realty, was targeted by fair housing opponents even in 1971.

“They were breaking our windows,” he said. “They were tying up our telephones, jamming our phone lines to tell us to stop … selling homes in those communities.”

And in 1974, his wife and children faced violence as a biracial family living in Beverly.

(Courtesy Frank Williams)

(Courtesy Frank Williams)

“Our windows were broken,” Williams said. “There was a Molotov cocktail put in our front doorway. Our children on occasions had to run how because they were being chased by the youngsters who were living in community at the time.”

Underwood says the Fair Housing Act lacked an enforcement mechanism.

“HUD did not have enforcement authority under the Fair Housing Act, so all the enforcement of the law was done in the courts, up until then,” he said.

And change came slowly.

“The 1988 amendment to the ‘68 act is when we got teeth and could punish folks for violating the law,” Williams said.

Today, the organization says it embraces fair housing, and works to extend rights to the LGBTQ community as well.

“Fair housing issues not just limited to the transaction,” Underwood said. “There are lots of factors that dictate where somebody can choose to live. They may be overt, they may be subtle. And it’s not so much today an act of a door being slammed in your face, but just opportunities not being there for you.”

And anyone who worked on the issue 50 years ago still argues the work isn’t finished.

“Still, we’ve got a long ways to go,” Williams says.

As an overwhelming majority of Chicagoans still live in neighborhoods that are majority one race.

Follow Brandis Friedman on Twitter @BrandisFriedman

Related stories:

MLK’s Death, 50 Years Later: Revisiting the Day a Giant Fell

The Little Rock Nine: Remembering Extraordinary Courage 60 Years Later

How Gentrification Takes Shape Across Chicago Neighborhoods