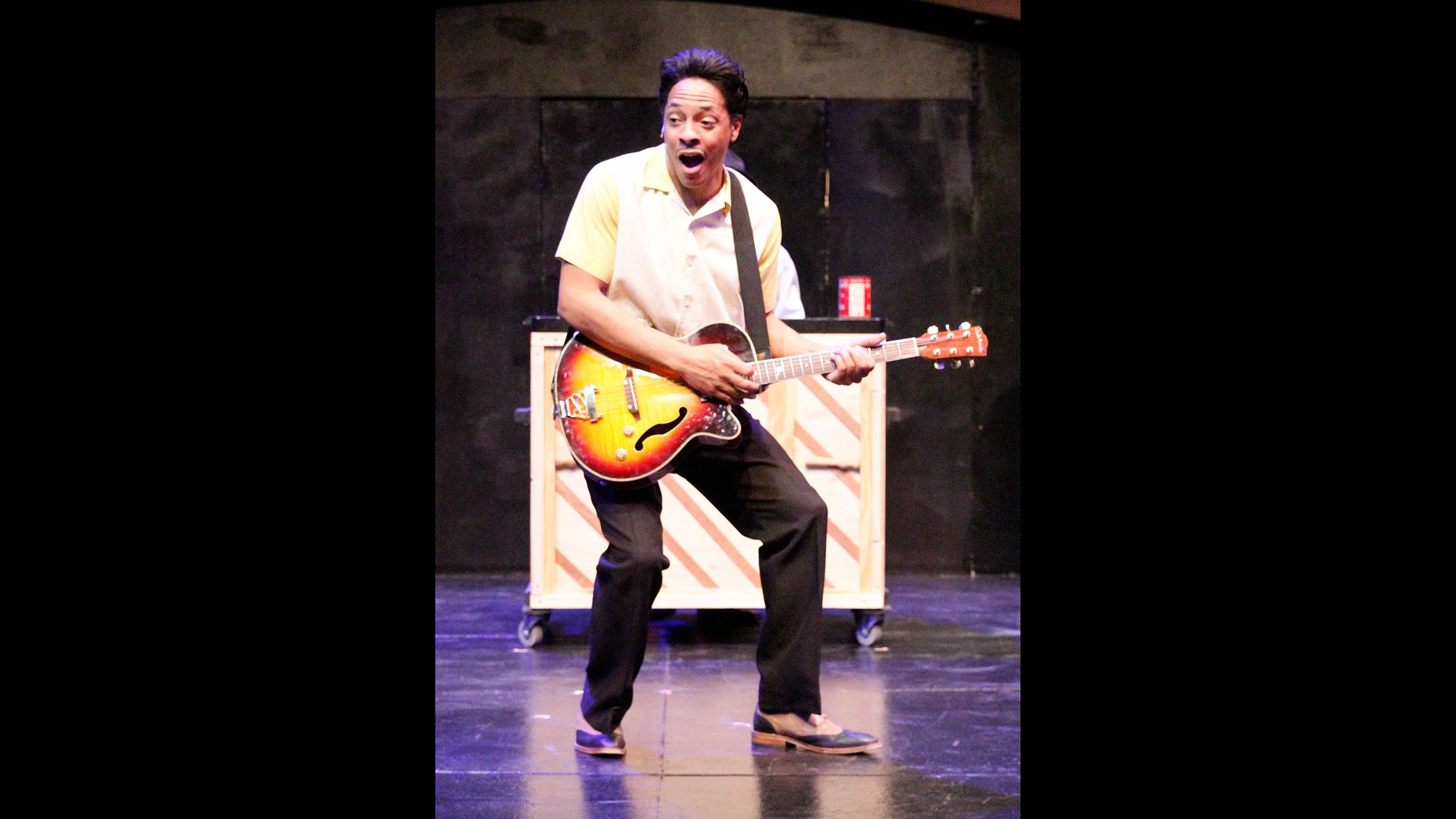

Lyle Miller as Older Chuck Berry in Black Ensemble Theater’s “Hail, Hail Chuck: A Tribute to Chuck Berry.” (Credit: Alan Davis)

Lyle Miller as Older Chuck Berry in Black Ensemble Theater’s “Hail, Hail Chuck: A Tribute to Chuck Berry.” (Credit: Alan Davis)

Long before Chuck Berry died in March 2017 at the ripe old age of 90, he was revered as the granddaddy of rock ‘n’ roll. The man who early on described himself as playing “black hillbilly/country music,” Berry savvily transformed that sound, drawing on deep, bluesy roots and a gift for zesty, mischievous lyrics and irresistible rhythms to create a new form – one that first beguiled both black and white teenagers in the 1950s, a time of intense racial segregation.

His music would then propel the likes of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and countless others. And it is that, and more, that feeds the story told in Black Ensemble Theater’s rollicking new show, “Hail, Hail Chuck: A Tribute to Chuck Berry.”

Written by L. Maceo Ferris, and directed by Daryl D. Brooks, the show is power-driven by the ever sensational music direction and arrangements of drummer Robert Reddrick whose rousing band (including Adam Sherrod, Gary Baker, Mark Miller and Oscar Brown) is perched high above the stage, and gives full volume to the actors’ vivid air guitar and air-piano playing.

Vincent Jordan, center, as Young Chuck Berry in Black Ensemble Theater’s “Hail, Hail Chuck: A Tribute to Chuck Berry.” (Credit: Alan Davis)

Vincent Jordan, center, as Young Chuck Berry in Black Ensemble Theater’s “Hail, Hail Chuck: A Tribute to Chuck Berry.” (Credit: Alan Davis)

The show closely follows the Black Ensemble formula as an iconic artist near the end of his life (here in Berry’s post-duck walking days, but still a showstopper) looks back at the long and winding and often rocky road that got him there. And with such songs as “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Maybellene,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “No Particular Place to Go” and others – all long ago imprinted in our pop music DNA – there is a familiar joy in the room, even if Berry’s life was full of turmoil as well as celebrity. (You also might find yourself thinking about the unshared credit for several of those unparalleled songs as you learn about how Berry never properly credited or compensated his early collaborator, pianist Johnnie Johnson, for his contributions.)

It all began in St. Louis, where Berry, a child of the Depression era, grew up with an abusive father who served as a deacon and wanted his son to focus on church music rather than turning to the guitar and “the devil’s music.”

Berry rebelled, fled home at 17, and was soon arrested and convicted of armed robbery and sent to a reformatory for three years. It would not be his last experience with incarceration, but as it happened, it was where he first became part of a band.

Lyle Miller (Credit: Alan Davis)

Lyle Miller (Credit: Alan Davis)

His first big break came when he made an impression on Johnson, who had a permanent gig at The Cosmo, a St. Louis nightclub, and where he first parlayed his “new sound” to an enthusiastic audience. It was also at The Cosmo that Berry met and wed Themetta, the woman who stuck with him (not always happily) for 68 years, many of which he spent on the road.

When Johnson’s band traveled to Chicago in 1955, the pianist introduced Berry to blues great Muddy Waters and, by extension, to Leonard Chess, the fabled record producer who helped propel him to fame (and to a national cross-racial audience).

A tour to Mississippi and other Jim Crow states would reinforce the notion that no amount of celebrity – and he had already racked up a number of chart toppers – would erase racism, the constant indignities of being kept out of decent hotels and restaurants, and the outrage from white patents triggered by an appearance on TV’s “American Bandstand.”

It was in 1959, after Berry had established his own upscale club in St. Louis – one that attracted a mixed-race audience – that things went bad and he was arrested under the Mann Act for transporting a minor across state lines for indecent purposes. (He said she was coming to work as a hat-check girl.) Sentenced to three years in jail, he emerged as a very different and far angrier man.

But there was still much performing and recording to do, a brief but successful label switch to Mercury Records (attended by all the money issues that have long plagued musicians), and a documentary directed by Taylor Hackford, and produced by the Stones’ Keith Richards (for whom Berry had great animosity). Designed to celebrate Berry’s 60th birthday by way of the filming of two of Berry’s 1986 concerts, it came very close to not happening as a result of the musician’s temper tantrums.

Vincent Jordan (Credit: Alan Davis)

Vincent Jordan (Credit: Alan Davis)

The show unspools quite organically, with superb performances by Lyle Miller as the older Berry and Vincent Jordan as his youthful incarnation. (Jordan stepped into his role barely a week before the show began, and aced it both vocally and dramatically, and he and Miller, a BET veteran, make a fine pairing. Both men sing and move with panache.)

Kelvin Davis and Rueben Echoles also are outstanding as, respectively, the older and younger Johnson, with Davis grabbing fierce hold of Johnson’s late-life outburst against Berry, and Echoles dancing up a storm.

As Berry’s wife, Kylah Williams beautifully limns her changing stages, from rather prim young woman to pleading wife and mother, with Cynthia Carter as her wilder friend.

Dwight Neal makes a convincingly wise and generous Muddy Waters, with fine turns by Trequon Tate as Bo Diddley, Jeff Wright as both Leonard Chess and a dissipated Keith Richards, John Wesley Hughes as a fiery Taylor Hackford, David Stobbe as a corrupt manager, and Lemond Hayes (an eye-catching dancer), Brandon Lavell and Christopher Taylor all part of the ensemble. Alexia Rutherford’s costumes add just the right flash and style to each character.

And by the end there is no doubt about it: That Berry songbook can still get you “Reelin’ and Rockin.’”

From left: Vincent Jordan, Dwight Neal, Reuben Echoles, Trequon Tate (Credit: Alan Davis)

From left: Vincent Jordan, Dwight Neal, Reuben Echoles, Trequon Tate (Credit: Alan Davis)

![]()

“Hail, Hail Chuck: A Tribute to Chuck Berry” runs through April 1 at the Black Ensemble Theatre, 4450 N. Clark St. For tickets ($55-$65) call (773) 769-4451 or visit www.blackensembletheater.org.

In ‘The Wolves,’ the Tensions Beneath a Fierce Team Spirit

In ‘The Wolves,’ the Tensions Beneath a Fierce Team Spirit

Feb. 22: Talk about timing: The Chicago premiere of Sarah DeLappe’s tour de force mix of verbal and physical athletics and teen angst comes as the U.S. women’s ice hockey team wins the 2018 Olympic gold medal.

In Lyric’s ‘Cosi,’ a Spirited Toast to the Imperfections of the Heart

In Lyric’s ‘Cosi,’ a Spirited Toast to the Imperfections of the Heart

Feb. 20: The production of “Cosi fan tutte” now at Lyric Opera of Chicago is a beauty. And in its playful but unquestionably bittersweet exploration of love, fidelity, betrayal and the unreliable nature of both men and women, it could easily have been written yesterday.

In ‘Bunny Bunny,’ Tapping Into Gilda Radner’s Sad Clown

In ‘Bunny Bunny,’ Tapping Into Gilda Radner’s Sad Clown

Feb. 15: You will catch only a brief glimpse of the big explosion of hair, but in “Bunny Bunny” at Mercury Theater Chicago you will fully feel the manic energy and rapid-fire comic responses of Gilda Radner.