What do you get when you put two of Chicago’s preeminent architecture critics together?

A thought-provoking book about the city’s storied architecture called, “Who Is the City For? Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm in Chicago.”

Writer Blair Kamin and photographer Lee Bey teamed up on the project that explores the inequities in the built environment of Chicago.

Read an excerpt of the book's introduction below.

This book, my third collection of Tribune columns published by the University of Chicago Press, is loosely framed around a central issue of our time: equity. What can architecture, traditionally the province of the rich and powerful, do to make cities like Chicago more equitable, serving poor, working- , and middle-class people, not just the 1 percent? A related question can be asked of the fields of transportation and urban planning, which in the wrong hands have led to such notorious projects as freeways that divide Black neighborhoods from white ones or sever one part of an impoverished neighborhood from another.

The question applies, too, to the field of historic preservation.

Whose history gets remembered and whose history is erased, either by bulldozers or by willful ignorance? In short, who is the city for?

Let me start by clarifying that I take equity to mean fairness or jus[1]tice in the way people are treated rather than the term’s economic meanings—a share of stock or the value of a piece of property after debts are subtracted. This emphasis on fairness has significant implications for architecture and the built environment. One side of town shouldn’t have bigger, more amenity- packed parks than the other just because it’s inhabited by the wealthy. If anything, the poor parts of a city should have the prime parks, because their residents live in far worse conditions than the rich.

That was among the essential points of my 1998 series of articles examining the problems and promise of Chicago’s greatest public space, its nearly thirty miles of beaches, harbors, and parkland along Lake Michigan. The series, “Reinventing the Lakefront,” documented a shameful disparity in acreage, access, and amenities between shoreline parks bordered by mostly white, affluent neighborhoods on the city’s North Side and those lined by largely Black, poor neighborhoods on the South Side. Since then, city agencies and the Chicago Park District have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the south lakefront, including architecturally ambitious pedestrian bridges and a harbor and marina that welcome parkgoers as well as boats. But any discussion of equity, I argue, should not be limited to apportioning resources fairly or controlling soaring rents.

A wiser alternative, in my view, is to expand and enrich the social meaning of “equity” by borrowing from its economic counterpart, so that, when we use the word, we’re talking about the physical environment that we share. Shared spaces encompass all aspects of the public realm, from sidewalks and streets to transit stations, to public libraries and public housing. Private buildings, be they skyscrapers, flagship stores, or museums, do just as much as, if not more than, public ones to shape the public realm.

At best, the public realm can serve as an equalizing force, a democratizing force. It can spread life’s pleasures and confer dignity, irrespective of a person’s race, income, creed, or gender. Shared space suggests shared destiny. Or, to put matters in terms of hard- nosed self- interest rather than empathetic generosity, the recognition that cities are shared ventures—and that the fate of one section of the city is inseparable from another—represents a far more viable long-term strategy than its opposite: containment of the poor, whether in ghettos, public-housing projects, or dysfunctional neighborhoods.

The shootings and thefts that have spread from Chicago’s South and West Sides to the downtown and affluent North Side neighborhoods like Lincoln Park make clear the costs of failing to address the root causes of long- festering problems associated with high concentrations of poverty. No neighborhood is an island, as the shattered glass of North Michigan Avenue storefronts hit by smash-and-grab thieves and the fatal May 2022 shooting of a teenager in Millennium Park near “the Bean” reveal.

To be sure, the notion that Americans can share anything may seem incredibly naive in light of the nation’s deep political and cultural divides, or the way metropolitan areas like Chicago are fractured by chasms of race and class. Indeed, as the columns collected here reveal, the on- the-ground reality in Chicago often falls painfully short of my ideal of urban equity. But the columns also show the power of architecture and urban design to aid the prospects of both communities and individuals.

Revered as the birthplace of modern architecture and for its singular role in the development of modern city planning, Chicago presents a still- relevant stage for analyzing the human impact of the urban drama. Its litany of influential projects spans centuries and has shaped design throughout the world, from the pathbreaking skyscrapers of the 1880s to the triumphant, albeit belated, 2004 opening of Millennium Park. The city’s architecture and urban-design pratfalls, like the demolished public- housing high- rises of the Robert Taylor Homes and Cabrini-Green, are as notorious as its exemplary buildings are glorious.

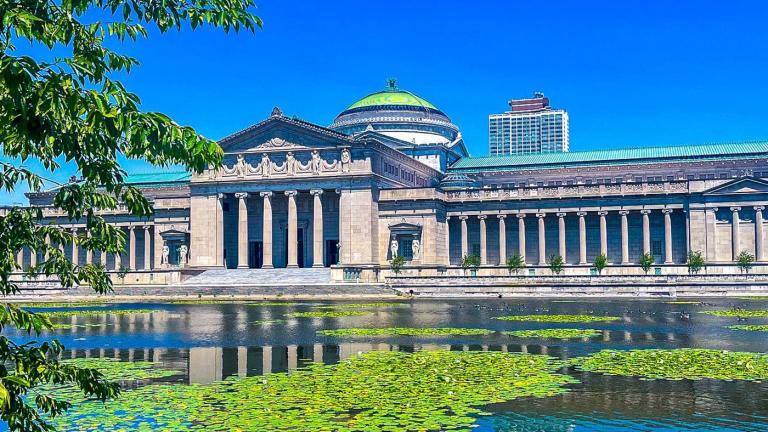

(Credit: Lee Bey)

(Credit: Lee Bey)

As I wrote in my first collection, quoting the urban historian Perry Duis, Chicago is “the great American exaggeration,” expressing at larger scale—and often in excruciating contrast—design trends evident in smaller cities. It gives us the best of the best and the worst of the worst of American urban life, a role it has reprised of late—heroically, with bold new skyscrapers like Jeanne Gang’s St. Regis Chicago tower, the world’s tallest building designed by a woman, and, tragically, with more than eight hundred homicides in 2021, its highest total in decades. By comparison, New York and Los Angeles, the nation’s two largest cities, had a combined total of about 980 killings in the same year.

Like my first two collections—Why Architecture Matters: Lessons from Chicago (2001) and Terror and Wonder: Architecture in a Tumultuous Age (2010)—this one covers a roughly ten- year span. It, too, was tumultuous, though there was no repeat of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, carried out by Islamic extremists, that made the World Trade Center’s twin towers collapse in a heap of smoke and ash.

In this case, the terrorism came from within—the January 6, 2021, assault on the temple of democracy, the US Capitol, by pro–Donald Trump insurrectionists trying to overturn Joe Biden’s election. The nation was further jolted by a pandemic that lasted more than two years and disrupted nearly every aspect of life; the racial reckoning that followed the police murder of George Floyd; life- and property-destroying storms and other consequences of worsening climate change; and rising income inequality. All had an impact on architecture and urban design.

Reprinted with permission from Who Is the City For?: Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm in Chicago by Blair Kamin with photographs by Lee Bey, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2022 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.