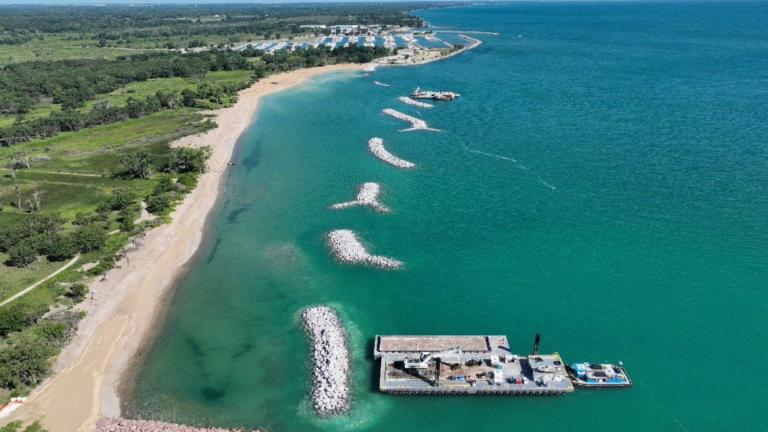

Thompson Road Farm, now owned by The Land Conservancy. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Thompson Road Farm, now owned by The Land Conservancy. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Lisa Haderlein has a folder full of topographical maps and centuries-old land surveys, all representing pieces of a puzzle it will likely take decades to fit together.

The documents hold clues to a landscape that no longer exists: the natural state of the 300 acres of farmland The Land Conservancy of McHenry County just purchased with the intention of restoring it to its pre-settlement condition.

What Haderlein, the conservancy’s executive director, sees on those sheets of paper — wetlands and sprawling, sunlit oak forests — is almost impossible to reconcile with the scene in front of her eyes — plowed fields and murky woods choked with invasives.

Everywhere she looks she sees damage that needs to be undone, alterations made to the land that need to be reversed.

That’s the task the conservancy has assigned itself. Reset the clock, erase the present, and bring the future in line with the past.

STEPPING UP

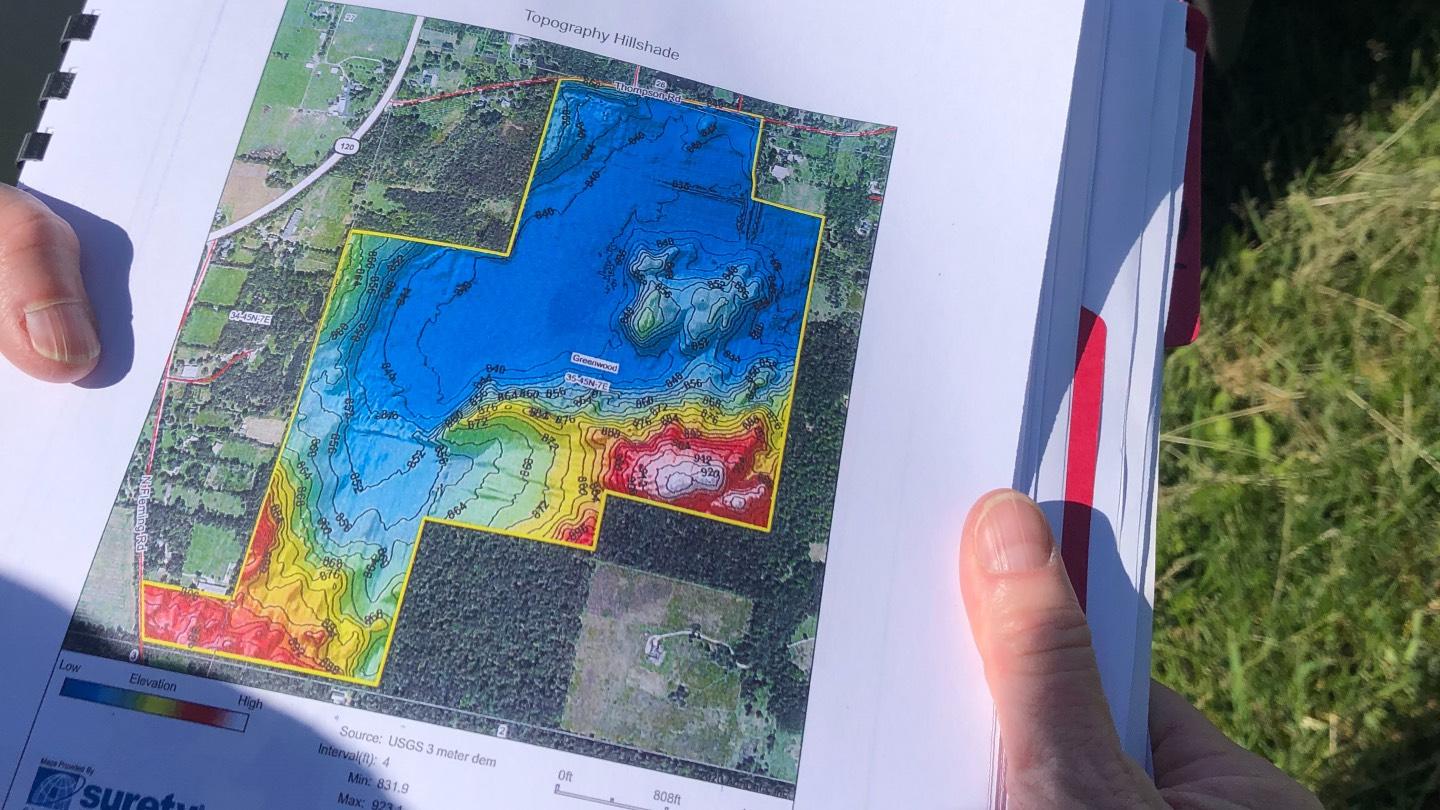

A topographical map of Thompson Road Farm shows the low-lying land, in blue. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A topographical map of Thompson Road Farm shows the low-lying land, in blue. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Properties come up for sale all the time in McHenry County. What made these 300 acres, known as the Thompson Road Farm, so special and worth pursuing by the conservancy was their location at the headwaters of Boone Creek, one of the highest quality streams in Illinois, Haderlein said.

Public and private entities have protected 1,000 acres of land within the creek’s watershed and Thompson Road Farm would add to that network, helping to filter and manage the water that eventually flows into the creek.

Adding to the farm’s significance, she said: Nearly one-third of its acres are peatland, a globally rare ecosystem notable for its ability to absorb and store massive amounts of carbon. While the peat soil at Thompson Road has been farmed up until recently, recovery is possible once natural hydrology is restored.

For the conservancy, the question wasn’t so much if the organization should attempt to buy the property, but how.

The tiny nonprofit owns just 650 acres. (It helps protect another 2,000 acres of private land through conservation easements.) Increasing its portfolio by 50% would be a heavy lift, but one it was willing to attempt, particularly once the conservancy found a willing partner in the village of Bull Valley, said Haderlein.

Between grant dollars and a $1.2 million loan, the conservancy cobbled together the $2.25 million purchase price for the land. It was a huge swing, but that’s what the times call for, Haderlein said.

Climate change and the alarming trends of species extinction and habitat loss demand that conservation organizations, regardless of size, think bigger, she said.

“More groups need to do more,” said Haderlein. “(Thompson Road) is four times larger than anything we’ve ever done. To me, that’s sort of the challenge we’re in right now. We all need to step up our game.”

TAKING STOCK

Lisa Haderlein, executive director of The Land Conservancy of McHenry County, sharing the vision for Thompson Road Farm. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Lisa Haderlein, executive director of The Land Conservancy of McHenry County, sharing the vision for Thompson Road Farm. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

On a sunny morning in early June, Haderlein took stock of the conservancy’s new acquisition, like a homeowner who’s just taken possession of a fixer-upper, already visualizing renovations.

“See that rise near the road? That’ll be a small parking area for a loop trail that will come to a viewing platform,” she said.

If this were an HGTV series, the transformation of Thompson Road would be accomplished over the course of an hour, culminating in a montage of “before” images dissolving into revelations of the stunning “after.”

In reality, restoration work is incremental and slow-going.

“Succession planning” is a term that’s been on Haderlein’s mind lately, an acknowledgement of the fact she might not be around to see the end result of gears she’s putting into motion at Thompson Road today.

“This is a multi-generational project,” she said. “We have to chunk it down into pieces.”

Here are those pieces, still very much in the “before” phase.

BUYING TIME

Drainage infrastructure at Thompson Road Farm. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Drainage infrastructure at Thompson Road Farm. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

“One hundred years ago, this was marsh,” Haderlein said.

You can see, she said, pointing to distant fields, where the earth is a noticeably darker color. “Those are clearly wetland soils.”

Drainage tiles and pipes underlie roughly one-third of Illinois cropland, and half of all farmland in Indiana and Ohio. This subsurface network siphons water from the soil, lowering the water table and making it not only easier to farm the land, but more productive.

Ever driven past fields of corn or soybeans and noticed what seems to be a creek running through the land? That’s almost surely a drainage channel. Same for the ditches running alongside highways and back roads. This is how farmers turned Midwestern swamps into the nation’s bread basket.

At Thompson Road, aging clay tiles have been cracking under the weight of modern equipment they weren’t built to withstand and water has crept back to the surface, a telltale signal of where those breaks have occurred. The farm’s inner wetland is fighting to break free.

“The hydrology’s all messed up here. The water’s not moving through the land the way it should,” said Haderlein.

She’s got a guy who has both the know-how and the machinery to remove the tiles, and he’s volunteered to do so for free at Thompson Road in his spare time. It’s a process that will take years.

But this summer, the land that’s farmable at Thompson Road is still being leased for planting while the conservancy buys time, Haderlein said. The organization needs to raise the funds to purchase a whopping amount of native plant seed mix — enough for roughly 150 acres — at $500 an acre.

The goal is to seed the fields after fall harvest to begin reestablishing native wetland plants.

NOT ALL GREEN IS GOOD

Thompson Road Farm: sea of reed grass. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Thompson Road Farm: sea of reed grass. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Though labeled a farm, plenty of the acreage at Thompson Road has been left wild, which isn’t the same as natural. Haderlein knows better than to conflate what appears to be an abundance of greenery with a healthy ecosystem.

There’s an area of the property that could be mistaken for a “meadow” but is in fact a sea of reed canary grass, a noxious invasive species that’s the wetland equivalent of buckthorn.

This aggressive plant forms a monoculture that can dominate a landscape, squelch biodiversity, constrict waterways, and decrease the retention of nutrients and carbon. It was once actively promoted to farmers by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as excellent for cattle foraging, Haderlein said. Now reed canary grass is on land manager’s “least wanted“ lists.

Bringing the grass under control is a long-term proposition, one that requires a kitchen-sink approach of prescribed burns, mowing, herbicides, repeated tilling or even excavation.

The conservancy already conducted a prescribed burn elsewhere at Thompson Road and then brought in an ecologist to sift through the area in search of native plants. The art of identifying dormant perennials is called “cadaver botany,” Haderlien explained, and the ecologist spotted plenty at the farm that could thrive once invasives are cleared.

“There should be a lot more diversity in the landscape,” she said. “In a good wetland you’d have golden alexander, marsh marigold, Joe pye weed, swamp and common milkweed, meadow rue.”

Even moreso than flowering plants, native shrubs have been decimated by invasives, to the point that a lot of people don’t even know what the native shrub species are. Haderlein lists nannyberry viburnum, red twig dogwood, hazelnut and currant bushes as some of species that should be found at Thompson Road. Instead, honeysuckle and autumn olive have taken hold, another example of a Department of Agriculture recommendation gone awry, she said. Farmers were once encouraged to plant them as natural hedges.

INTO THE WOODS

Thompson Road Farm: The woods are overgrown with invasive species. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Thompson Road Farm: The woods are overgrown with invasive species. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Jung family, who sold Thompson Road to the conservancy, had owned the farm since the 1960s. Nancy Jung founded the Bull Valley Riding Club on the property in 1963.

Five miles of equestrian trails weave through the farm, part of a broader network of 60 miles of paths. In the past, these trails were solely for private use by club members, but now under the conservancy’s ownership, Thompson Road’s trails will be available to the public for hiking, bird watching and winter activities like cross-country skiing, as well as riding.

Mown grass in some places, dirt in others, the trails skirt the edge of the sea of canary grass before entering the property’s woods. Sun gives way to shade as the close-knit trees form a dense canopy of foliage overhead.

It’s a classic forest, in the sense that this is what Midwesterners have come to believe a forest looks like, Haderlein said.

“This is what we’ve seen,” she said. “This is what we think woods are.”

But the woods at Thompson Road are a far cry from the landscape settlers would have encountered in the 1800s.

Surveys show that the surrounding area was once 40% oak forest, half of which was gone well before 1900. The trees were chopped down either for use as lumber or cleared to make way for crops.

The oaks found today at Thompson Road are too often hemmed in by more aggressive non-natives, like cherry and the dreaded buckthorn. Bittersweet vines slither up trunks, tightening their grip as they go, smothering and strangling their hosts.

What oaks really like is space and sunlight. It’s a description that runs so counter to the picture most people have of forests, the conservancy is developing signage for its oak forests that specify “this is healthy.”

It’ll be a while before the signs are needed at Thompson Road. “There’s a lot of restoration that needs to go on in those woods,” Haderlein.

Time to get to work.

WTTW News will periodically check in on progress at Thompson Road Farm.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]