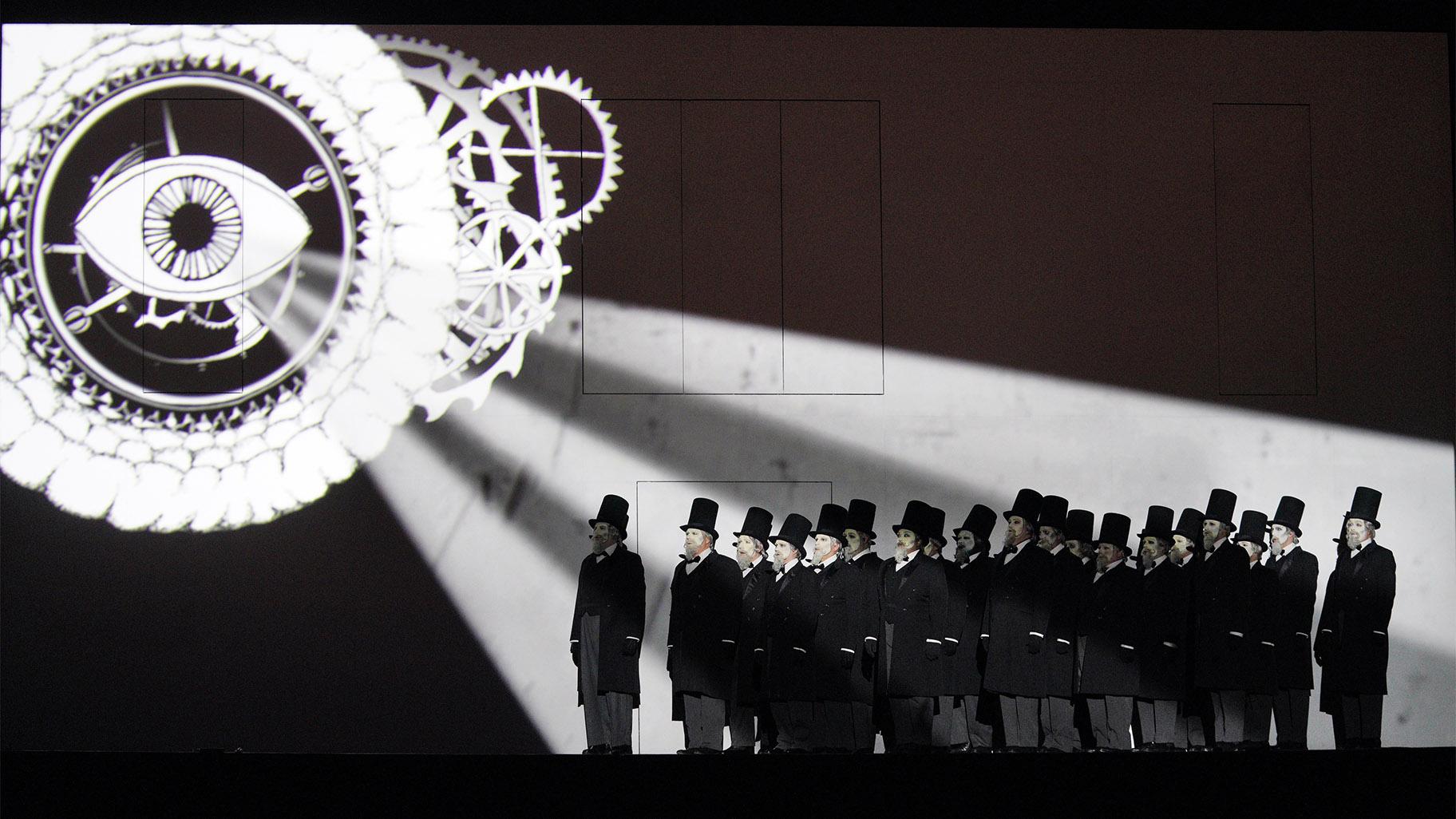

The Company of “The Magic Flute” (Credit Cory Weaver)

The Company of “The Magic Flute” (Credit Cory Weaver)

During the past week I attended three radically different performances that challenged the notion of classical music in each of their very particular ways.

First, the Lyric Opera production of “The Magic Flute,” Mozart’s last and altogether brilliant opera is a tale of love and death, cruelty and perseverance. It involves a multiplicity of personalities and at Lyric it comes all dressed up — and mostly overwhelmed — by a highly sophisticated and elaborate use of 21st century state-of-the-art animation. The work dates back from 1791, also the year of Mozart’s death at the age of 35.

Then, a Chicago Symphony Orchestra concert featuring exquisite classical works by Mendelssohn, Bruch and Mozart, with Robert Chen, the CSO’s masterful Concertmaster since 1999, as the soloist in Bruch’s “Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor.”

And finally, “Homecoming,” the latest entry in the CSO’s MusicNOW series, this was a showcase of the work of four contemporary composers who play fast and furiously with classical music forms.

Mozart composed 22 operas during the course of his tragically brief but brilliant life. The more you listen to any and all of Mozart’s music, whether for the opera, symphony, or other forms, the more you realize that everything he wrote is an extension of the emotional power of the human voice and its instrumental counterparts.

Those who saw the movie “Amadeus” might recall how the composer is seen transforming the shrill rant of his wife into the glorious, fiendishly difficult and angry coloratura aria for the Queen of the Night.

The Queen in “The Magic Flute,” whose daughter, Pamina is the object of Prince Tamino’s love, is being held captive by her rival, the elusive High Priest Sarastro, and his evil enforcer, Monastatos. At the same time, Tamino’s companion, the hapless Papageno, a bird-catcher, is in search of a wife of his own.

This production of the opera, created by the London-based multimedia theater company called 1927, and first produced in 2012 at the Komische Oper Berlin, was originally directed by Suzanne Andrade and Barrie Kosky, with Tobias Ribitzki directing its revival. But it is very much the invention of animation designer Paul Barritt. The fact that his work is a hugely ingenious, state-of-the-art visual experiment, with components of both humor and horror — spiraling musical notation and birds, giant black monsters, shapely women, a cooperative noose suspended from a tree, and much more — is undeniable. So is the fact that the production might well have been envisioned as a way to attract a younger audience to the opera house. The artful updating of Donizetti’s “The Elixir of Love ‘‘ earlier this Fall showed this could be done in a far more subtle way.

The relentless eye candy here also is immensely distracting, often overwhelming the singers, perching them in precarious positions, and no doubt making their blocking something of a nightmare with their precision-tuned positioning on stage essential to the animation. In the process, much of Mozart’s music gets “upstaged” as does the essential emotional exchange between the real-life performers and their characters, despite the fine Lyric Orchestra musicians and conductor Karen Jamensek.

The singers get a bit less lost in the second act, or maybe it’s just a matter of finally getting used to all the electronic traffic. And in many cases they even manage to soar, with baritone Huw Montague Rendall as an easily engaging and comic Papageno; the beautiful soprano Ying Fang winningly vulnerable yet steely as Pamina, the princess held hostage; tenor Pavel Petrov as prince Tamino, Pamina’s determined and honorable suitor; Lila Dufy as the fierce and angry Queen of the Night, who stops the show with her soaring coloratura; the impressive bass, Tareq Nazmi, as the easily commanding High Priest who oversees a series of life-altering trials for the lovers; tenor Brenton Ryan as his truly demonic slave, Monostatos; Mathilda Edge, Katherine DeYoung and Kathleen Felty as the chorus of Three Ladies; Denis Velez as Papagena (whose name is a play on the German word for parrot), the answer to Papageno’s quest for a wife; and an excellent male chorus in Abe Lincoln-like stovepipe hats.

“The Magic Flute” — an opera that, when left unfettered, reinforces the notion that “music is the food of love” — will be performed Nov. 7, 11, 14, 17, 19 and 27. For tickets visit LyricOpera.org.

Guest conductor Marek Janowski acknowledges Robert Chen following a performance of Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Credit Todd Rosenberg)

Guest conductor Marek Janowski acknowledges Robert Chen following a performance of Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Credit Todd Rosenberg)

Thursday evening’s CSO concert featured a trio of beautiful works, with guest conductor Marek Janowski, artistic director of the Dresden Philharmonic, working without a score. as he led the final piece on the program - Mozart’s exuberant “Symphony No. 41 in C Major (‘Jupiter’),” which was performed with the orchestra’s usual brilliance.

The concert opened with Mendelssohn’s “The Hebrides Overture,” a work I had never before heard in a live performance. An altogether ravishing piece, just 10 minutes long, it carries you out to sea. It vividly captures a sense of the wild waves washing around the remote Scottish islands of its title with its feverish use of the strings, winds and brass, its melodic beauty, and its stormy but ever lyrical urgency. A brief but exquisite work.

Next was Bruch’s “Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor,” an ideal showcase for Robert Chen and his honey-toned Stradivarius. It announces itself with a brief and muted sound from the timpani, then the initial sound of the violin, and subtle plucking from the basses and cellos. There is a lovely fluidity and warmth to Chen’s playing, and he and his fellow musicians easily captured a sense of the composer’s inner landscape, with the sound of the French horns and other brass adding a sense of grandeur.

Chen was back in the concertmaster’s chair for the Mozart symphony, a work of great energy that soars on the composer’s genius for capturing both the individual voices of the orchestra and their interplay. It also was a vivid reminder of how Mozart’s music always has a singing quality — the human voice expanded and glorified. A different form of opera in a way, and in this case, a powerful reminder that his music is innately animated, and not in need of any further animation or other enhancement.

Composer Ted Hearne joins conductor Michael Lewanski, musicians from the CSO and guests following a performance of Authority that concluded the first CSO MusicNOW program of the 2021-22 season.

Composer Ted Hearne joins conductor Michael Lewanski, musicians from the CSO and guests following a performance of Authority that concluded the first CSO MusicNOW program of the 2021-22 season.

Finally, the CSO’s MusicNOW program, is curated by Jessie Montgomery who has had several of her rhythmically fascinating works, including “Strum,” and “Coincident Dances,” performed by the CSO in recent months. For the next three seasons, Montgomery will serve as the CSO’s Mead Composer-in-Residence. This one-night-only concert, performed by musicians of the CSO, offered examples of just how far what we term “classical music” can be pushed, pulled, fragmented, reimagined and even notated.

With “new music” there really is a need to listen to a work multiple times before fully grasping it, in part because the structure can be so unfamiliar. But here are some first impressions, along with this note: Michael Lewanski, the conductor of the program, had to deal with a slew of new musical languages, no doubt a daunting test, but one he handled with impressive aplomb, as did the various musicians involved.

The concert opened with Elijah Daniel Smith’s “Scions of an Atlas,” a work of crazy syncopations, dissonance and a slew of wide-ranging experiments in sound involving the strings, winds and brass, with unusual accents courtesy of percussion from Ian Ding and Mio Nakamura on piano. It culminated with a big crescendo and then a potent silence.

Montgomery’s contributions came in the form of two songs performed by the rich-voiced soprano Whitney Morrison who needed greater clarity in her diction. The lyrics for the first song, “Loisaida, My Love” — whose title is a play on the Lower East Side neighborhood in Manhattan where Montgomery grew up — are the work of Bimbo Rivas, a Puerto Rican-born poet who also was a force in developing affordable housing projects in that rundown area in the 1970s and ‘80s.

The second piece, “Lunar Song,” with lyrics by J. Mae Barizo, was written as an ASCAP commission to celebrate the Leonard Bernstein centennial in 2019. I wish Montgomery had tapped more deeply into Bernstein’s musical eclecticism in the piece.

Up next was Nathalie Joachim’s intriguing “Seen,” a quintet for woodwinds superbly performed by musicians Emma Gerstein on flute, Anne Bach on oboe, John Bruce Yeh on clarinet, Keith Buncke on bassoon and David Griffin on horn. The five brief sections of the piece were inspired by artist Whitfield Lovell’s portraits of five unknown African Americans and the everyday objects they might, or might not, have felt connected to. And while I doubt I would have guessed that was the underlying scenario, the shifting moods — a bit of lively Copland-esque sound, then a more mellow tone, a bit of syncopation and more — variously brought to mind a kite in the wind, a broken doll, and a spinning pinwheel. It’s a work I need to hear again.

The last and most complex work on the program was Ted Hearne’s “Authority,” no doubt a hair-raising challenge for both its 12 musicians and Lewanski. Lewanski clearly had to invent a new sign language of sorts to signal them. Scored for winds, harp, piano, electric guitar, keyboard and strings, the “Authority” is a complexly layered, cacophonous work of immense rhythmic chaos and agitation, with overlapping instrumental voices and frenzied rhythmic bursts. And I cannot begin to imagine how the score was notated. Hearne said “Authority” was an abstract attempt to suggest how we handle viewpoints that are not our own.”

All the composers were in attendance at the concert and made brief, charming personal statements about their work.

Follow Hedy Weiss on Twitter: @HedyWeissCritic