On Saturday, the exhibition “El Greco: Ambition and Defiance” opens at the Art Institute of Chicago, which partnered with the Louvre and the Grand Palais for the show.

We asked Art Institute curator Rebecca Long to tell us about the great and complicated Greek painter who studied in Venice and Rome before becoming a leading figure in the Spanish Renaissance.

‘El Greco’ is a nickname

El Greco was born Domenikos Theotokopoulos and lived from 1541-1614. The nickname denotes his Greek heritage.

He settled in Spain

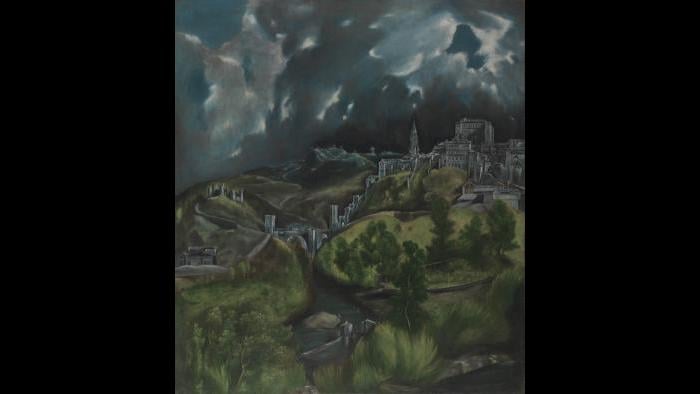

El Greco was from Crete, Greek’s largest island. Back then it was the Kingdom of Candia, part of the Republic of Venice. After working in Venice and Rome, the artist settled in Toledo, Spain, for the last 35 years of his life.

… But didn’t settle, professionally speaking

“To me what’s fascinating about him as an artist is, you’ve got this young artist who trains and becomes certified as a master painter in the style of Greek icon painting on the island of Crete,” Long said. “He could’ve made a career for himself as an icon painter, and that clearly wasn’t good enough. I think it probably had to do with the fact that he was aware that there was greater wealth in Venice, and Crete was part of the Venetian Republic. So that kind of upward-striving you see at a very early stage, and it continues through his career.”

He was bold

A story persists that he offered to repaint the Sistine Chapel. According to Long: “That is a legend, but it carries a certain amount of truth. Michelangelo’s ‘The Last Judgement’ in the Sistine Chapel is full of nude figures, and there was debate at the time about whether that was appropriate, and later on another artist painted little loincloths on them, so in the context of that debate, it makes a certain amount of sense. The story goes that El Greco offered: ‘If it needs to be repainted, tear it down and I can do a better one.’ Which is awfully bold.”

He thought one of the world’s greatest painters wasn’t so great

Michelangelo had died six years before El Greco arrived in Rome. “We have copies of two books that we know El Greco owned in his lifetime, and he made notes in the margins,” Long said. “One of them is Vasari’s ‘Lives of the Artists’ which is published in 1568, and for Vasari, Michelangelo was the God of Painters, and the marginal note about Michelangelo from El Greco says something along the lines of ‘Well, he could draw but he didn’t know anything about color.’ He was very dismissive.”

He thought highly of himself

“He knows that there’s a lot of wealth around the papal court in Rome, so he picks up and moves to Rome and has a pretty good entry into noble Roman society – he is given an introduction and is taken under the wing into the court of a papal nephew, Cardinal Alexander Farnese,” Long said. “And he did something to tick off Alexander Farnese. We have a very apologetic, yet still arrogant letter from El Greco to Cardinal Farnese saying, ‘I’m sorry I did that thing, but I don’t think it should have bothered you.’ But we don’t know what that thing was that offended the cardinal, but at any rate he gets kicked out of the palace.”

His reputation languished

“He dies in 1614, and he’s really forgotten about until the end of the 19th century,” Long said. “He was seen as very eccentric, mystical, too Catholic. There was just not an appreciation of him and some of his major artworks are put into storage. And it’s really the avant-garde writers and artists who rediscover him, the most famous would be Picasso, who knew of him from growing up in Spain, but also there were several works by El Greco in Paris that were available to Picasso. One painting in our show, a loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ‘The Vision of Saint John,’ is said to be the direct model for Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ at MOMA, one of his most famous proto-Cubist figure paintings.”

The Art Institute of Chicago owns an important work

The first exhibition devoted to El Greco was at the Prado in 1902. In 1906, the Art Institute purchased “The Assumption of the Virgin,” El Greco’s first major Spanish commission. They did so at the suggestion of American impressionist painting Mary Cassatt. The large painted altarpiece (15 feet tall and weighing 331 lbs.) was restored for this exhibition.

A painter of masterpieces of Catholic tradition, he probably wasn’t Catholic

“He would’ve been raised in the Eastern Orthodox Church, and there’s no evidence that he ever converted formally to Roman Catholicism when he moved to Italy and Spain,” Long said. “There’s no evidence of him joining a confraternity or religious order or having any real connection other than his friendship and business relationships with patrons who were active in the church.”

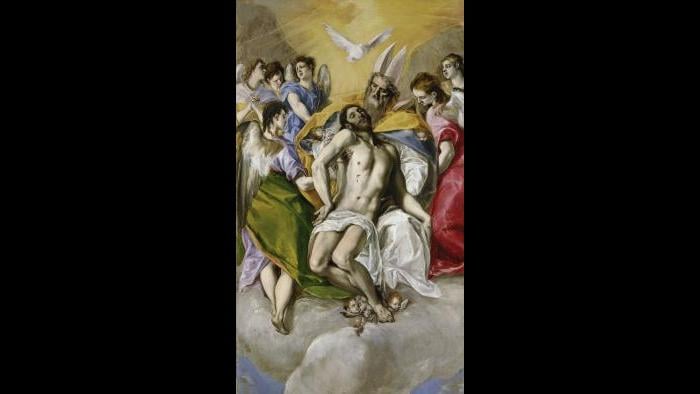

His last painting was for his tomb

“The show contains an altarpiece on loan from that Prado in Madrid that is generally considered to be his last painting before his own death, and it was intended to decorate his own family tomb,” Long said.