Saturday marks the 100th anniversary of the Chicago race riots of 1919.

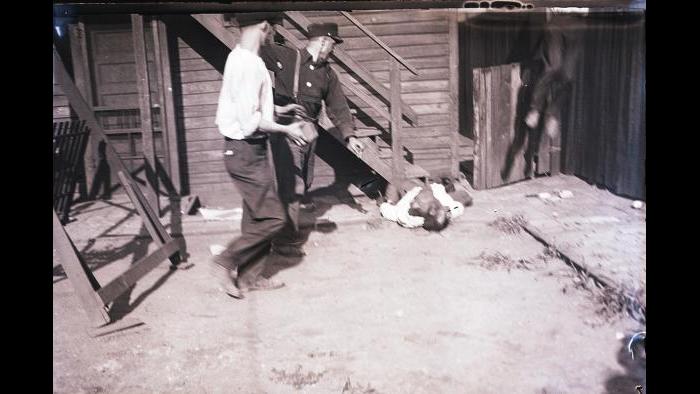

For one week that year, angry white mobs terrorized black Chicagoans with violence. In defense, black residents fought back. By the end of the week, 38 people were dead (23 black, 15 white), more than 500 were injured and thousands were displaced from their homes.

The Chicago Race Riot 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19), comprised of numerous local organizations and institutions, developed programming centered on the riots. A wide range of activities take place Saturday across the city.

CRR19’s goal is to launch a public art project marking the deaths from the riots. Presently, there is one historical marker at 29th Street and the lakefront path for Eugene Williams, whose death on July 27, 1919 was the catalyst for the riot.

The group also wants to raise awareness about the riots, and also to make sure “everyone learns about this history and that we have a day of reconciliation … to promote healing and social justice,” said Franklin Cosey-Gay, executive director of the Chicago Center for Youth Violence Prevention.

“We want to highlight the history because it helps us understand why communities look the way they do today,” Franklin said.

Before Williams’ death, thought leaders such as Ida B. Wells, an investigative journalist and an early leader in the civil rights movement, predicted a violent uprising.

At the turn of the 20th century, black southerners began to leave the South and migrate north in search of new economic opportunities for their families and to escape the terror of Jim Crow. Known as the Great Migration, more than 7 million black people moved from the mid-1900s to the 1970s.

The influx of black migrants to northern cities like Chicago was one area of conflict. Increased competition for jobs was another.

Additionally, black men fresh from serving on the frontlines in World War I began to challenge their second-class citizenship status. They sacrificed their lives for America and were not interested in maintaining the status quo, said Julius L. Jones, assistant curator at the Chicago History Museum.

Williams, 17, and four other black boys were swimming in Lake Michigan on a warm summer day in July 1919. The group unknowingly drifted to the “whites-only” side of the beach. A white man threw rocks from the shore at Williams, killing him.

Police did not arrest the man who was identified as the one responsible for causing his death.

“The murder coupled with various social and economic political [issues] were responsible,” said Jones.

From July 27 to Aug. 3, white mobs attacked black people in the streets of Chicago while black people retaliated and fought back. Gov. Frank Lowden dispatched the Illinois National Guard to Chicago.

Riots in other cities across the U.S. also experienced riots between white and black residents. The summer of 1919 is also known as the Red Summer.

Activities for Saturday include a bike tour in Bronzeville, panel discussions featuring journalist and critic Lee Bey, a walking tour and more.

Related stories:

Hundreds of Black Deaths in 1919 Are Being Remembered

Illinois Cancels Band from Fair Lineup Over Confederate Flag

What Could Reparations for Black Americans Look Like?