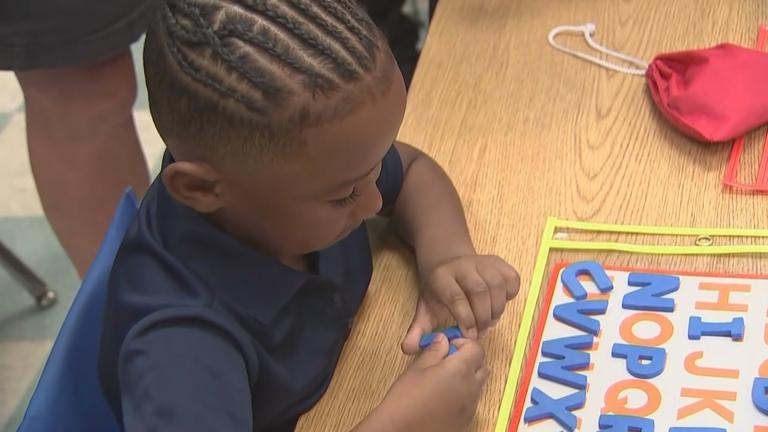

New research by the University of Chicago finds that disadvantaged children who received high-quality early childhood education are reaping the benefits of that program 50 years later in terms of better life outcomes – and so are their offspring.

“This research builds on existing evidence that high-quality early childhood programs, beginning at birth, produce significantly better life outcomes for children,” said University of Chicago professor James Heckman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist who led the research. “The effects have a beneficial impact on the immediate family and extend to later generations, multiplying the value of the original investment and boosting the effectiveness of existing investments in education.”

Heckman, along with co-author Ganesh Karapakula of the university’s Center for the Economics of Human Development, examined the long-term impacts of the iconic Perry Preschool Project. Started in the 1960s, the project aimed to study the lifetime impacts of providing high-quality preschool experiences to socioeconomically and developmentally disadvantaged African American children.

From 1962-1967, 123 children ages 3-4 with below average IQ scores were enrolled in a two-year program in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The program provided them with “an enriched early environment,” that included preschool instruction and supplemental weekly home visits with staff, said Heckman, who has been studying the group for about a decade. Participants were compared to a group that didn’t receive such education and researchers have tracked their development periodically throughout their lives.

The latest research surveyed participants, who are now in their 50s and many of whom have children of their own, on a number of measures, including the well-being of their offspring.

Researchers found participants had significantly better life outcomes at midlife compared to those who weren’t involved in the project, including increased employment and cognitive and socioemotional skills. They also found reduced criminal activity, especially violent crime, among male participants, which Heckman called “a major boost to the earnings of families.”

Participants also had more stable marriages and were more likely to provide their children with a more stable two-parent home, building the foundations for stronger families that resulted in larger gains for their children.

“High-quality early childhood education for disadvantaged children builds valuable personal and interpersonal skills, contributes to stronger families and can be an effective way to lift generations out of poverty,” he said.

Heckman found participants’ children were more likely to be in good health, complete college and to be employed despite living in similar or worse neighborhoods than the children of nonparticipants.

Those outcomes are due to parental engagement with children and improved family life, according to Heckman. “The results are a consequence of improving, bolstering families,” he said, dispelling the notion that an individual’s future is shaped by where they live. “This is not a consequence of changing zip codes.”

Heckman said the findings can’t be generalized to a much broader population or used as evidence to support universal preschool programs. “This program targeted disadvantaged children,” he said. “Evidence from this study and others like it show … targeting disadvantaged children and families with disadvantaged children is a very effective strategy.”

Note: This story was originally published May 16, 2019. It has been updated.

Contact Kristen Thometz: @kristenthometz | [email protected] | (773) 509-5452

Related stories:

Poll: Illinoisans Say Improving Schools Among Top Issues Facing State

Report: Illinois Just ‘Getting Started’ in Addressing Children’s Needs

Study: Parental Incarceration Impacts Children’s Health into Adulthood