The patch designed by NASA for a Northwestern-led mission to study how space affects the physiology and metabolism of mice. (NASA / Northwestern University)

The patch designed by NASA for a Northwestern-led mission to study how space affects the physiology and metabolism of mice. (NASA / Northwestern University)

Twenty laboratory mice will be launched into orbit next week as part of a Northwestern-led research mission to learn more about the physiological effects of living in space.

Northwestern scientists Fred Turek and Martha Vitaterna are leading the NASA-funded project to study how the near gravity-free environment of space impacts the mice’s metabolism, circadian rhythms and other physiological systems. Researchers expect the findings to lead to better protections for astronauts’ health during long-term space missions, including possible trips to Mars.

“Because a trip to Mars and back is expected to take several years, we need to determine how the gut’s microbiota might be altered in zero gravity over long timescales,” said Turek, director of Northwestern’s Center for Sleep and Circadian Biology, in a statement.

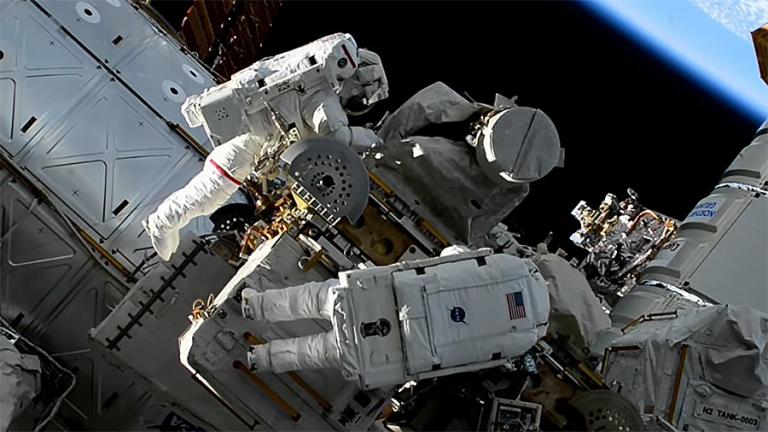

The research mission, officially named “Rodent Research-7,” is one of five science investigations scheduled to launch in the early morning of June 29 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. After boarding the SpaceX Dragon, a Falcon 9 rocket will launch the mice on their way to the International Space Station.

Turek, Vitaterna and seven team members have been in Florida since last week preparing for the launch. Alongside the mice mission, the scientists are among dozens of investigators who continue to examine data from astronaut Scott Kelly – and his identical twin brother, Mark – during Scott’s one-year mission aboard the ISS. Results from the twins study are scheduled for publication later this year.

Fred Turek and Martha Vitaterna (Courtesy Northwestern University)

“It’s important to understand how space travel may impact the circadian system, since it coordinates so many biological processes” said Vitaterna, deputy director of the Center for Sleep and Circadian Biology, in a statement. “The exertion of liftoff, absence of gravity and confined living arrangement all add to the stress of life in space, and the key to adapting may be in the body’s ability to maintain harmony across systems.”

Ten of the 20 mice aboard the International Space Station will spend a record 90 days in orbit. Research on the space-bound mice will be compared with observations of mice in three different control groups, including one living in a NASA simulator that replicates the minute-by-minute conditions inside the space station – except with gravity.

“With the [Kelly] twins we only had two subjects and we could not prescribe that they eat the same, or live similar lifestyles while Scott was in space,” Vitaterna said. “With this new project, we will be able to control for diet and also further examine the liver, spleen and fat to learn the ways in which individual components affect one another.”

Also participating in the mice study are scientists from the University of Illinois at Chicago and Rush University Medical Center.

Contact Alex Ruppenthal: @arupp | [email protected] | (773) 509-5623

Related stories:

Do Mice Prefer Chicago or its Suburbs? Lincoln Park Zoo Explores