Over the past year, the increasing tensions and rhetoric between North Korea and the U.S. have raised fears of the unthinkable: a nuclear attack. And earlier this week, North Korea launched a missile that U.S. officials say was the most advanced the rogue nation has ever produced.

That launch comes just days before the 75th anniversary of the event that ignited the nuclear age, an event that took place at an unlikely location on Chicago’s South Side.

For many years before World War II, the biggest event at the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field was the annual football faceoff between the Michigan Wolverines and the Chicago Maroons.

Tens of thousands of fans packed the grandstand for those games, but little could any of those fans have known that under that grandstand a far more significant event would enshrine the stadium in history. It happened on Dec. 2, 1942, a few years after the university ended its football program and Stagg Field was becoming an aging relic. A 41-year-old Nobel Laureate physicist decided it was a good place to conduct what would turn out to be an Earth-shattering experiment.

“It was the first time there was a project of this scale in science that involved a range of scientists all working here on one large project,” said Eric Isaacs, EVP for Research, Innovation and National Laboratories at UChicago.

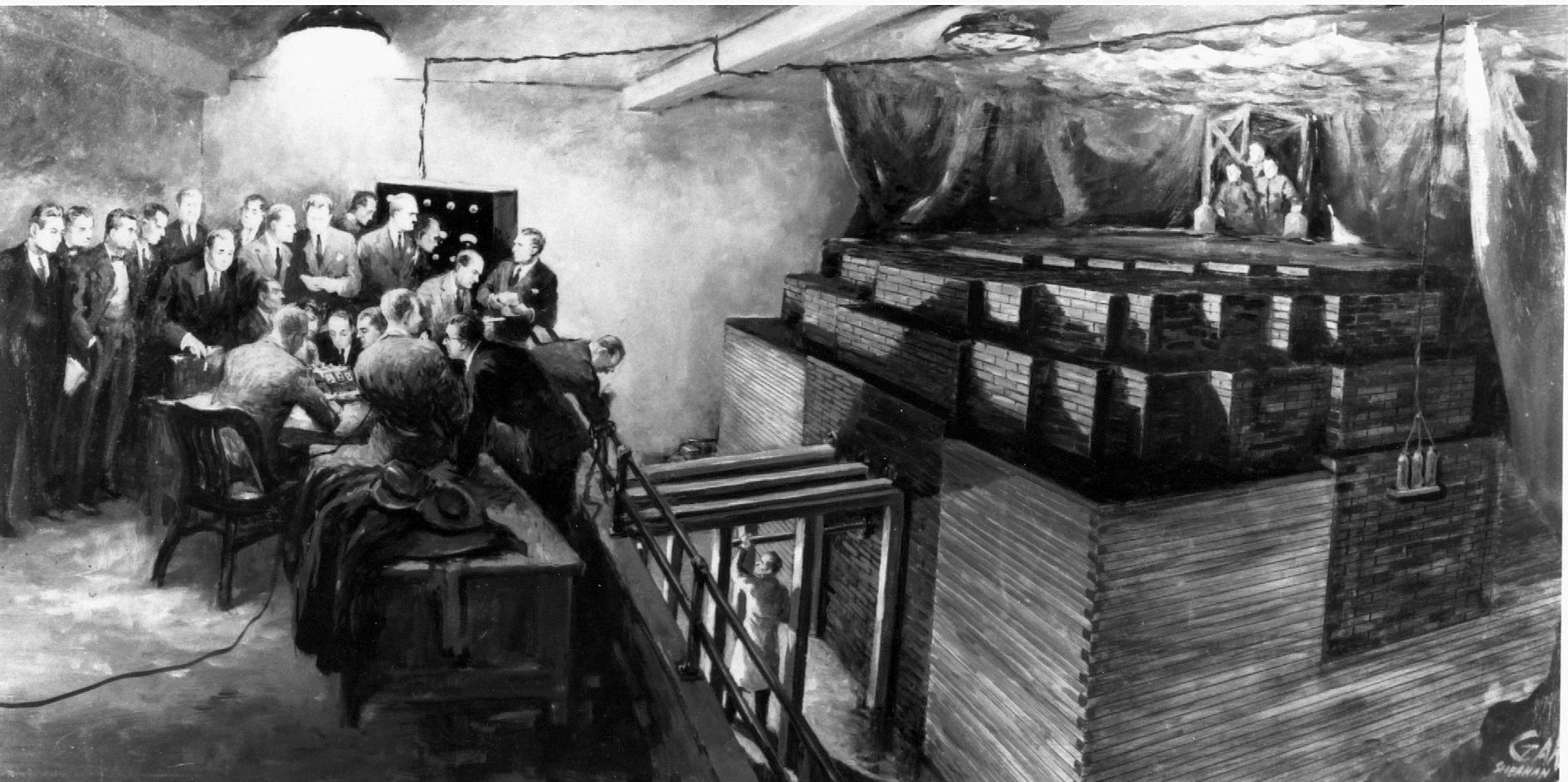

An illustration depicts the scene on Dec. 2, 1942, under the west stands of the old Stagg Field at University of Chicago, where scientists Enrico Fermi and his colleagues achieved the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. (Chicago Historical Society / University of Chicago)

An illustration depicts the scene on Dec. 2, 1942, under the west stands of the old Stagg Field at University of Chicago, where scientists Enrico Fermi and his colleagues achieved the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. (Chicago Historical Society / University of Chicago)

The mastermind behind that large project was Italian immigrant Enrico Fermi, who had become a luminary in physics long before he reached Chicago. In his native Italy he was dubbed the “pope of physics” by his colleagues and students. And in 1938, he received the Nobel Prize for his research into nuclear reactions. By that time, German scientists had discovered that fission, or splitting the atom, was possible. And when word reached the anti-Nazi world, the race was on to achieve the next monumental step; a race that intensified when the U.S. entered World War II.

“They knew if they could multiply that energy that it could be tremendously powerful. They understood it could be weaponized—they understood that even before they did it,” said Isaacs.

Fermi and his family escaped fascist Italy, landing in New York City where he became a professor at Columbia University. But at the behest of Albert Einstein, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered the best minds in physics to come together to work on a nuclear weapon before the Germans. And he believed the best place to assemble that team under one roof was at the University of Chicago.

With Fermi at the helm, the experiment conducted under the Stagg Field grandstand was inelegantly called Chicago Pile-1.

“They basically built a pile made up of wooden braces, a large number of black graphite bricks and uranium,” Isaacs said.

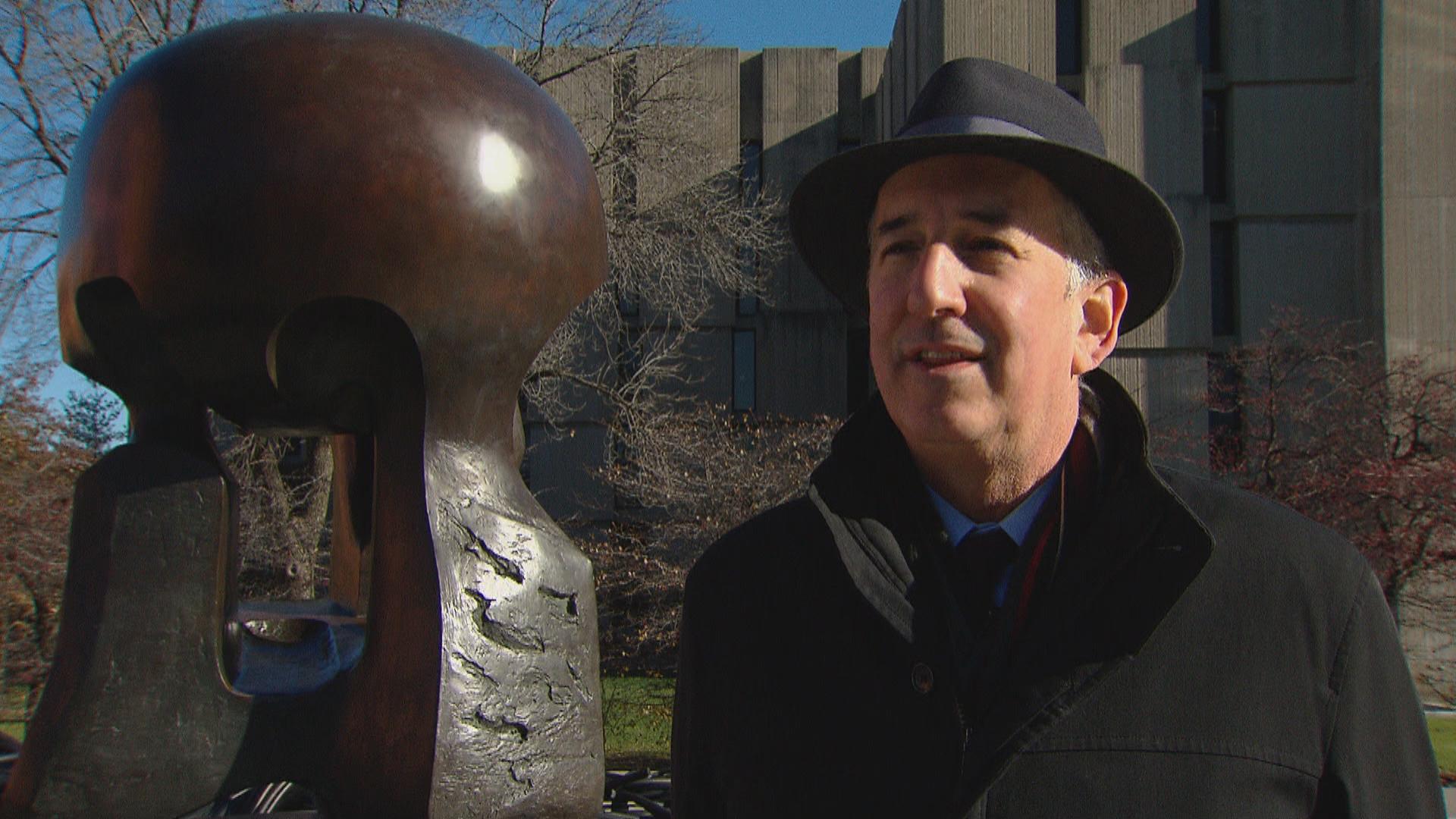

Eric Isaacs, CEO of UChicago Argonne

Eric Isaacs, CEO of UChicago Argonne

For the historic experiment, rods made of cadmium that could be pulled in and out of the pile were used to absorb uranium atoms and ensure a possible chain reaction didn’t get out of control.

After a month of intensive labor, Fermi and his students began the test on the morning of Dec. 2. But a few hours later, on the brink of history, Fermi told everyone to take a lunch break. The experiment resumed in the afternoon and physicist George Weil removed the control rod that launched the nuclear age.

Among those present at the landmark achievement was Nobel Prize-winning physicist Arthur Compton, who raced to break the news to James Conant, the chairman of the National Defense Research Committee in Washington.

In a spontaneously coded exchange, Compton reported, “The Italian navigator has landed in the new world,” to which Conant asked, “How were the natives?”

Compton’s reply: “Very friendly”

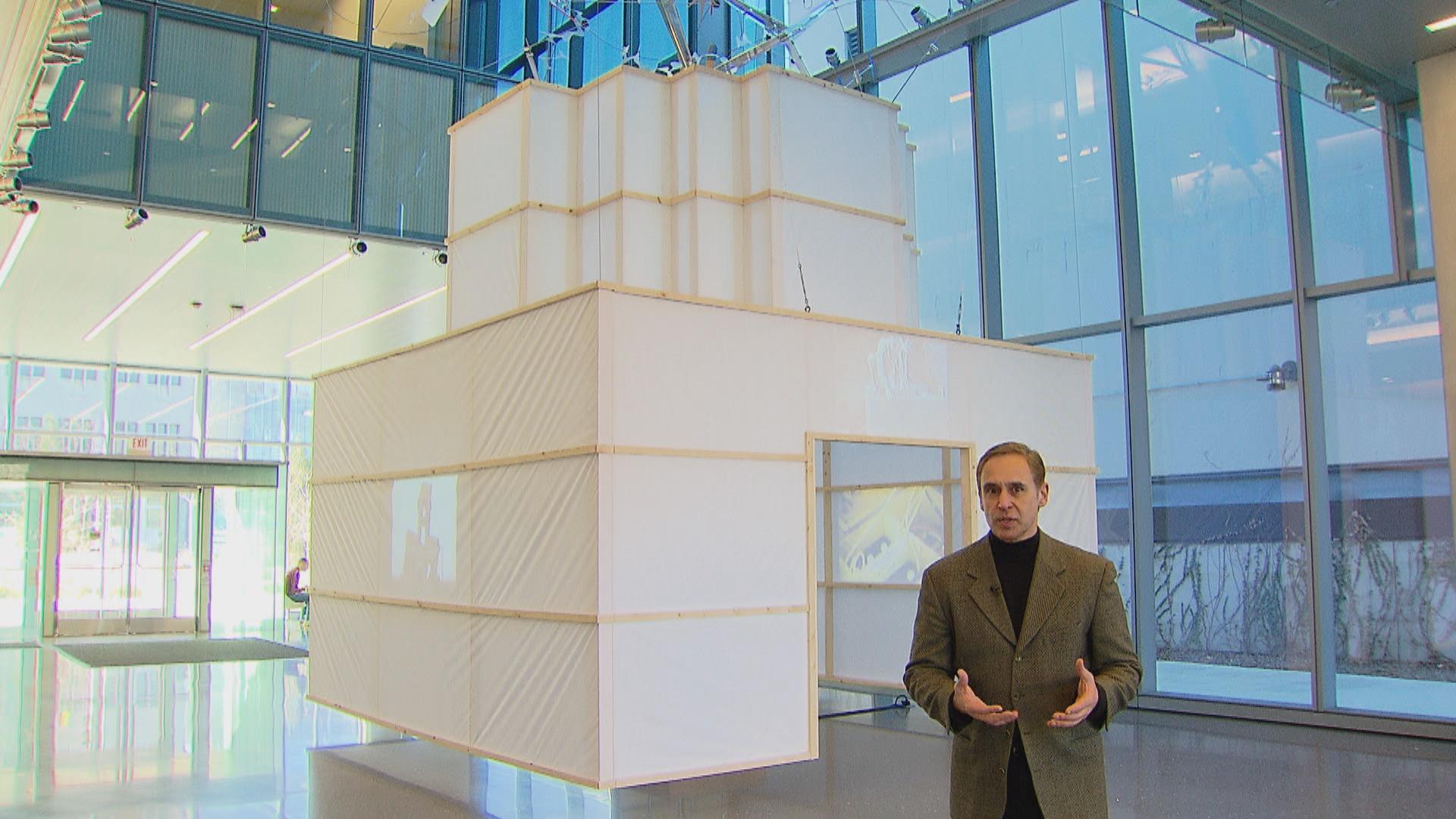

At the University of Chicago, an exhibit has been created to commemorate that historic experiment of December 1942. It’s a replica of the size of Chicago Pile-1, inside of which that first sustained nuclear chain reaction occurred.

A little over two-and-a-half years after the success of Chicago Pile-1, Fermi was among the scientists present at Los Alamos, New Mexico, to witness the outcome of what he achieved: the first test of a nuclear bomb informally called the Gadget. Even the best minds in the world didn’t know if it would work or what would happen—but at 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, they found out.

Only three weeks later, a similar bomb was the first to be used as a weapon.

Late in 1945, atomic scientists alarmed by the potential of the new age published their first bulletin, ironically, at the University of Chicago. The Bulletin is still published today, albeit digitally, and tracks, among other things, how close humanity is to nuclear annihilation.

“Technology continues to move at an extraordinarily rapid clip,” said Rachel Bronson, president and CEO of the Bulletin. “We know that it’s going to bring enormous benefits ... but there’s also the risks. And that’s what we focus on, because if we can manage those risks, we’re going to be able to reap the benefits.”

After the war, Fermi remained at the University of Chicago in its Institute of Nuclear Studies. Many scientists there actively opposed the testing and construction of nuclear weapons. But Fermi never publicly revealed his thoughts. He died of stomach cancer on Nov. 28, 1954 at the age of 53 and is buried at Oak Woods Cemetery, about 10 blocks due south of where he reached the new world.

An enigmatic sculpture by English artist Henry Moore marks the spot where Fermi and his team made history.

Moore admitted that it is a combination skull and mushroom cloud, which he says symbolize the hopes and fears launched on that auspicious December day.

![]()

The University of Chicago hosts a series of events and exhibitions Friday and Saturday to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Get complete information here about “Reactions: New Perspectives on Our Nuclear Legacy.”

Video: Argonne National Laboratory’s Lego video of the first sustained nuclear reaction.

Related stories:

New UChicago Course Examines Legacy of Nuclear Age

New UChicago Course Examines Legacy of Nuclear Age

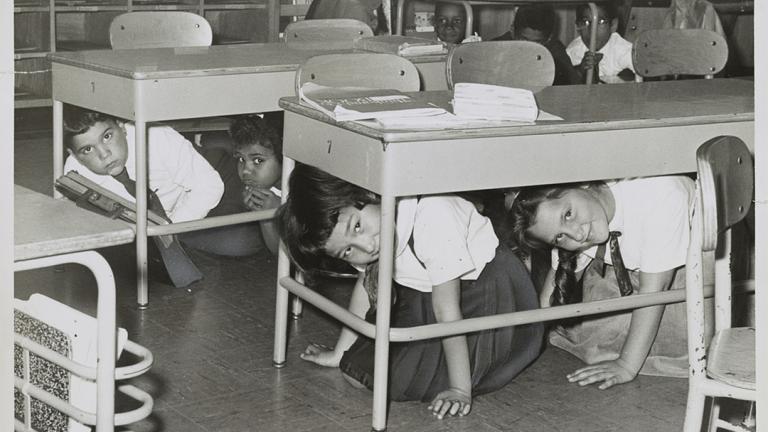

Nov. 20: The days when Americans fretted over an imminent U.S.-Soviet nuclear showdown might be over, but the consequences of a new nuclear age are still reverberating today.

BGA: Illinois Nuclear Plants Leak, Spill Radioactive Water

BGA: Illinois Nuclear Plants Leak, Spill Radioactive Water

Nov. 21: Radioactive water leaking from Illinois nuclear power plants, despite promised safeguards—an investigative reporter on what’s been done.

Argonne National Lab Celebrates 70 Years of Cutting-Edge Research

Argonne National Lab Celebrates 70 Years of Cutting-Edge Research

June 21, 2016: Since its creation in 1946, Argonne National Laboratory has been at the forefront of scientific research. Lab director Peter Littlewood joins us to discuss 70 years of scientific discovery.