Sabella Nitti was sentenced to hang in 1923 for the murder of her husband Francesco Nitti.

The sentence was one that no other woman in Chicago had ever received. But Nitti’s case was different in more ways than one.

As an immigrant from the southern Italian city of Bari, Nitti barely understood English, and few people could communicate with her in the Barese dialect she used. Court proceedings were whirling bouts of confusion for the foreigner at the center of the story.

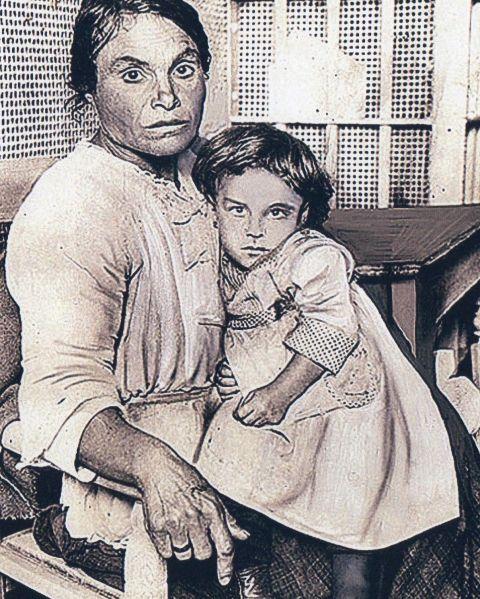

Unlike Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner, attractive women accused—and later acquitted—of murdering their lovers (and who inspired the musical “Chicago”), Nitti was unkempt, physically hardened by years of farm labor. Reporters took note of her appearance and poor dress, which played no small role in the proceedings.

Prosecutors and a deputy sheriff were eager to send a woman to the gallows for the first time, and journalists were keen on constructing a scandalous narrative. Even family members were interested in making a few dollars off Nitti’s belongings—the few she had.

Matters were made worse by Nitti’s defense attorney, Eugene Moran—a man plagued by mental illness that jeopardized the case he claimed for himself. While the facts seemed to point to Nitti’s innocence, Moran’s incompetence condemned her.

After Nitti was sentenced to death, Helen Cirese, a young, sympathetic attorney, stepped in to defend the Italian immigrant and appeal her case to the Illinois Supreme Court.

Chicago-based freelance journalist Emilie Le Beau Lucchesi chronicled Nitti’s story in her book “Ugly Prey” after poring over hundreds of pages of Springfield trial transcripts, legal documents, family records and newspaper articles.

Lucchesi joins us to discuss Nitti’s story and her new book. Below, a Q&A with the author.

![]()

Why do you feel that Sabella Nitti’s story is important?

I first saw Sabella Nitti’s photo in a book called The Girls of Murder City by Douglas Perry. That book focused on Belva and Beulah and the women who inspired. Sabella was a side character. I saw that photo and I did not see the ugly, vicious woman that she was described to be by the newspapers. I saw her as a very scared, vulnerable immigrant. I wanted to see what were the possibilities of telling her story. I requested this 700-page transcript from the state of Illinois archives. As I dug deeper, I realized how much this woman was innocent. It was only fair that we did a story where we pushed Belva and Beulah from the spotlight and focused on Sabella.

As your book’s title suggests, how relevant was Sabella’s appearance to her trial?

At the time, there was kind of a rash of lady killers who were glamorous, guilty and not one bit sorry. They’d go in front of a jury and they’d charm their way into acquittal. Sabella, in contrast, was very emaciated; she had had a hard couple of years. She was a farm woman and dressed the part of a farm woman. She was considered ugly by the men who were trying her. She had very haggard manners. She grunted. She was considered very foreign. They were able to use that to convince the jury that she was jury. For them it was important to finally get one of these lady killers, or so they thought, and not have to go to the media and explain that they weren’t able to get a conviction.

Women were objectified when Sabella stood trial. Do you think society has come a long way since then?

My hard instinct is no. I don’t think we have. I’m teaching an ethics course to lawyers coming up and one of the pieces of advice I have for them is to make their client look familiar. When it comes to women, I’d say that femininity still matters. There’s still this idea of who a woman should be in order to receive lenient treatment. I think there have been more Sabella Nittis and I think there will continue to be more Sabella Nittis. If anything, we’ll just see who the target group in question may evolve into, but we’ll always have someone who’s victim to that.

In 1923 Chicago, how shocking was the idea of a sending a woman to hang?

It was very shocking. The U.S. as a whole had kind of cooled off on the notion of hanging women after the execution of Mary Surratt, who was executed as an accomplice to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Americans, for the most part, had “cooled off” on the idea of hanging white women. The city itself was pretty scandalized because you had women in women’s groups who had stepped forward and said, “Women just got the right to vote, but we don’t make the laws, two women are attorneys, we’re not in the juries, we get sent out of the courtroom anytime something scandalous is brought up and the judge doesn’t want our pretty little ears to hear.” I think many women felt this was an example of women being subject to men ruling in favor of what they liked, which was pretty women. On the flip side, you had men who said, “Well, if women want the vote, if they want to be equal, then they have to accept the consequences that come with it.”

What would you like readers to take away from this book?

What I want them to take away is to consider women’s history. That’s what I’m trying to do, to write women’s history and consider women’s experiences. And to widen our lens as to how we view history, so that we’re not looking at the same stories told about the same people, but we’re opening up and considering more women’s experiences and that includes the immigrant experience – the people who were not in the society pages.

Below, an excerpt from “Ugly Prey.”

![]()

Part I

GUILTY

THAT MEANS A HANGING!

July 9, 1923

In the early afternoon, the jury filed back into the courtroom with a verdict. The twelve men kept their eyes low, diverted from the defendants’ table. They knew they were sending this middle-Aged woman, Sabella Nitti, and her young husband, Peter Crudele, to the gallows.

They had made the decision in the deliberation room, voting a dozen times until they came to agreement. It was the right thing to do, they believed, to bring Francesco Nitti’s killers to justice. But it didn’t feel right to send a woman to the gallows. She would be the first woman to hang in Cook County, and that was a heavy burden on the jurors’ consciences.

The audience in the courtroom read the jurors’ faces, trying to get a sense of what they decided. One man, a regular murder trial attendee, voiced his veteran opinion to the other courtroom enthusiasts. “That means a hanging!”

The audience in the courtroom read the jurors’ faces, trying to get a sense of what they decided. One man, a regular murder trial attendee, voiced his veteran opinion to the other courtroom enthusiasts. “That means a hanging!”

Peter stiffened in his wooden chair at the defendants’ table. At twenty- two, he was almost two decades younger than his wife, and he had picked up the English language soon after emigrating from the Adriatic Coast to the Chicago area a few years back. He understood what the observers were saying. They believed he was a doomed man and they talked about the possibility of him hanging as if they were watching a motion picture or reading a detective magazine.

Peter had a long oval face, dark hair, and pale skin. He hardened his jaw and locked his dark eyes on the desk in front of him. He was a handsome young man, and his good looks contrasted with his aging wife. Peter and Sabella had been married only two months when they were arrested, along with Sabella’s youngest son, Charley, for the murder of her former husband. Prosecutors claimed the mismatched couple had killed Francesco Nitti the previous July so they could be together.

Peter likely sensed how the spectators at the trial thought the worst of him and Sabella. The charges against Sabella’s son had been dropped just days before, and the boy sat in the gallery with the rest of the audience, eager to hear the fate of his mother and stepfather. The boy might have been one of the few people in the courtroom not hoping for a conviction.

From the audience, reporter Genevieve Forbes studied the defendants, paying attention to every foreign detail about the woman in particular. If it were up to Forbes, she would find Sabella guilty and hang the old woman that very night. Forbes was disgusted by Sabella. This little Italian woman was everything that Americans reviled about these invading Southern Europeans. Sabella didn’t speak English. She was dirty. Violent. Ignorant. Uneducated. She clung to her backward ways, and she clearly cared nothing for American rules and order. Maybe in Italy a woman was free to bludgeon her husband to death and marry a much younger farmhand. But there was a proper justice system in Cook County, which Forbes wrote about for the Chicago Daily Tribune. Later that day, she would sit at her portable typewriter in the newsroom on Madison Street and describe Sabella as the “dumb, crouching, animal-like peasant.”

At first glance, Forbes appeared to be Sabella’s polar opposite. Forbes was slender and light. She was not particularly pretty but she had fine features—a slender nose, thin lips, and light eyes. To Forbes, Sabella was a peasant who looked—and smelled—like she had just walked out of a field. Sabella was a compact woman with a muscular frame built during a lifetime of work. Her olive skin had deepened like tanned leather after years of toiling in the Mediterranean sun. She had long, thick black and gray hair that she piled onto her head in a messy bun and secured with pins and combs. Across the courtroom, her hair looked filthy, and several times Forbes wrote the word “greasy” in her notebook as a description of this little woman’s appearance.

If Sabella had been born under different circumstances, it would have been easy to describe her as pretty. She had fine, arched eyebrows and round, close-set eyes. She had a slender nose, a wide mouth, and a defined jawline. In another life shaped by school or cotillion, a young Sabella might have charmed men by looking up at them with a wide smile and long, fluttering eyelashes. But a lifetime of desperation and work under the sun made it easy for Forbes to call Sabella “grotesque” in the news reports.

It was not just her appearance that irked Forbes—it was her manners. Sabella appeared in public without a hat, which proved to Forbes that this murderer lacked any tact or class. And she showed up to court as if she was ready to work on a corn row. Sabella wore a long-sleeved dark work shirt to the trial and a heavy, long dark-blue skirt. Her skirt was full, but it had been shortened for work in the field. Her attire was far too heavy for a hot courtroom in July, and Forbes watched as the doomed woman took out a small square of fabric and wiped sweat off her brow.

Judge Joseph David peered down at the packed courtroom. The gallery was crowded with spectators who had read about the murder trial in the newspapers and wanted to be there for the big moment. Many of them were Italian, and Judge David suspected they might disrupt the courtroom after the verdict was read.

“Deputy Dasso,” Judge David ordered. “Tell your people in their language that if there is any noise or demonstration, the guilty person will be sent to jail.”

If Deputy Sheriff Paul Dasso cringed at the comment “your people,” he kept it to himself. He was not from Sabella’s home province of Bari, in southern Italy, nor was he even Italian born. He spoke the language of his parents’ homeland, but these were not his paesani. Sabella and Peter were dark, thin, and hardened by labor. Dasso was a round man who wore a three-piece suit that made him seem even larger. He was light skinned and his hair had turned white over the years. No one passing him on the street would have thought he was an Italian. It was probably a surprise for most of the spectators to see such a prominent man stand up and address the court in an Italian dialect.

Judge David looked at the jury. He was a slim man with downturned eyes that gave him the appearance of being sad or even sympathetic. He was neither. At times during the trial, he tried to warn Sabella’s attorney against making poor choices during questioning. But Judge David was primarily irritated during the trial, particularly with the difficulties in finding a proper translator. He frequently snapped at the Italians watching the trial from the gallery, and gave the impression he wasn’t fond of these people.

“Has the jury reached a verdict?” he asked.

The foreman, Thomas Murtaugh, stood. “We have, Your Honor.” Murtaugh passed two sheets of paper to Matthew Vogel, clerk of the court. Vogel unfolded the papers, and the crackling sound rolled around the quiet courtroom. The room was perfectly still. No one breathed loud or shuffled their feet. After a pause, Vogel spoke and his voice vibrated clearly around the courtroom. “We, the jury,” Vogel read, “find the defendant Peter Crudele guilty of murder, in manner and form as charged in the indictment, and we fix his punishment at death.”

Peter stared ahead and did not blink. But Forbes was watching every move he made, looking for muscle reaction and vein bulges. She scribbled in her notebook how his skin looked gray. He had white pox marks on his forehead, which contrasted against his skin.

Vogel moved the papers around. He brought the page with Sabella’s verdict to the top and read: “We, the jury, find the defendant Isabella Nitti, otherwise called Sabella Nitti, guilty of murder, in manner and form as charged in the indictment, and we fix her punishment at death.”

The stunned courtroom sat in silence. Sabella patted her hair and looked hopefully around the room. She hadn’t understood a word. Forbes inspected her from across the room. Stubby fingers, she wrote, ingrained dirt in finger nails.

The silence in the courtroom broke. Defense attorney Eugene A. Moran blurted, “Motion for a new trial.”

“Denied,” Judge David responded. “Clear the court.”

Forbes watched as the Italian women who sat in the back of the gallery avoided looking at Sabella as they filed out. Forbes didn’t speak a word of Italian, and she certainly had no knowledge of Sabella’s distinct Barese dialect. She eyed them as they left. They grinned at the verdict, she noted, they spent their days listening to the testimony and speculating on “how she got that young man.” They didn’t support her, Forbes assumed. They were against her and she was guilty.

No one seemed to remember in the moments after the verdict was read that Sabella did not speak English. Or at least no one bothered to translate the verdict so she would understand it. And there was nothing in anyone’s behavior that might have suggested to her that something was different about the day. The jury filed out of the courtroom, as they did at the end of each day. The women who sat in the back rows like they were patrons at a free opera had walked out without looking in her direction. That was typical, too. Her lawyer left abruptly, but he couldn’t communicate with her anyway. What clues did she have?

Sabella saw her oldest son, James, push his way through the crowd of spectators and burst out the courtroom doors. Her middle son, Michael, was notably absent. Her youngest son, Charley, calmly wandered into the hallway and bought an orange from the peddler.

The defendants were separated. Peter was led away to his cell in the men’s jail, and Sabella was led back to the women’s section on the fourth floor, just as she had been each day for the previous week.

Until someone translated the verdict, Sabella would not know she was scheduled to hang in just ninety-five days.

Related stories:

America’s Forgotten ‘Radium Girls’ Take the Lead in New Book

America’s Forgotten ‘Radium Girls’ Take the Lead in New Book

May 11: The author of a new book explores the lives of young factory workers exposed to radium in the 1920s.

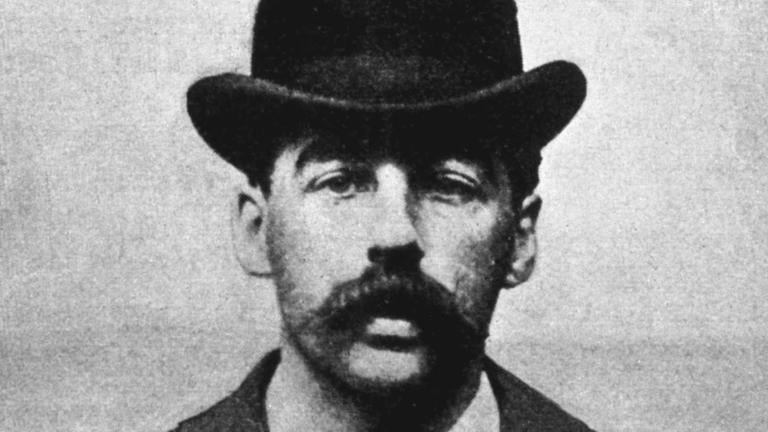

‘True History’ of H.H. Holmes Examines Life, Career of Serial Killer

‘True History’ of H.H. Holmes Examines Life, Career of Serial Killer

May 10: Adam Selzer, author of the new book “H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil,” joins us to discuss the latest chapter in a story that's already more than a century old.

‘Forgotten Chicago’ Uncovers History Worth Remembering

‘Forgotten Chicago’ Uncovers History Worth Remembering

April 20: For nearly a decade, the website Forgotten Chicago has documented the city’s storied past. Meet the site’s co-founder and editor, Jacob Kaplan.