Not that long ago, air pollution from burning coal made the Windy City more like the Smoggy City. Our local history expert Geoffrey Baer tells us how Chicago cleaned up its act. He'll also explore the Kentucky Colony that settled in the city and the history of a pediatric hospital on the South Side in this week's edition of Ask Geoffrey.

![]()

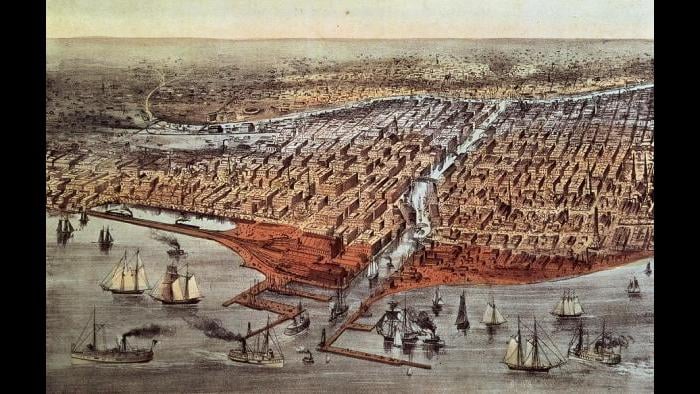

For much of its history, Chicago (and everywhere else) used mostly coal and wood to power factories and heat buildings. How did we deal with the tremendous pollution?

–Tom Sharp, Lincoln Park

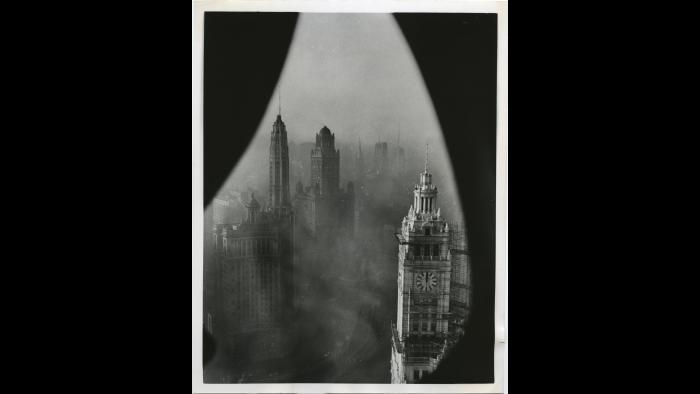

Looking at Chicago's gleaming skyline today, it's surprising to remember that not so long ago many of those buildings were black with soot from coal-fired furnaces and factories all over the city. Take a look back at old photos or films, though, and that skyline isn't so pristine.

During the Industrial Age belching smokestacks were looked at as a good thing – this meant the city that works was working! Eventually, though, we learned you can have too much of a good thing. Some days, pollution turned day into night, ruining clothing, blackening buildings, sickening Chicagoans and even stopping airplanes from taking off. Today, we can see a similar situation in countries like India, Iran, Pakistan and China where coal is still widely used.

The Chicago Tribune led the crusade against Chicago’s dirty air. The newspaper began reporting on the condition of the city's air as early as the 1870s. In one report, the author Rudyard Kipling is quoted as saying simply, "the air is dirt" after a visit to Chicago.

Dr. John Dill Robertson

One of the earliest agitators for clean air was Chicago health commissioner Dr. John Dill Robertson, who put forth the revolutionary idea that air pollution was just as serious as pollution of the water supply, exacerbating cases of influenza and tuberculosis. In 1919 he created women-led “smoke patrols” to monitor the air in their neighborhoods, enlisted nurses to spot violators of the city’s smoke ordinance which had been passed in 1880. He also rallied janitors to stop burning garbage. He even launched a “clean air week” to promote his agenda.

Dr. John Dill Robertson

One of the earliest agitators for clean air was Chicago health commissioner Dr. John Dill Robertson, who put forth the revolutionary idea that air pollution was just as serious as pollution of the water supply, exacerbating cases of influenza and tuberculosis. In 1919 he created women-led “smoke patrols” to monitor the air in their neighborhoods, enlisted nurses to spot violators of the city’s smoke ordinance which had been passed in 1880. He also rallied janitors to stop burning garbage. He even launched a “clean air week” to promote his agenda.

Chicago’s architects responded to the city’s grimy air with practical design strategies. For example, the walls of the Chicago Public Library (now the Chicago Cultural Center) were adorned with sparkling mosaics in part because the building stood across the street from the smoky Illinois Central railroad yard, which is now Millennium Park. Mosaics were easier to clean than paintings and plaster walls.

A little further north on Michigan Avenue, there’s also the 1929 Carbide and Carbon Building, which for years was covered in so much soot that Chicagoans grew to believe it was black. It wasn’t until the building’s conversion into the Hard Rock Hotel in 2004 that we got to see the green tile and gold trim that make the building resemble a champagne bottle. And even further north, the Wrigley Building’s striking white exterior of glazed terra-cotta shrugs off soot. William Wrigley Jr. had the 1921 building cleaned frequently and lit it with floodlights so that it would stand out like a beacon in Chicago’s gray skies.

Left: Carbide and Carbon Building in 1943. Right: Carbide and Carbon Building in 2009.

Left: Carbide and Carbon Building in 1943. Right: Carbide and Carbon Building in 2009.

Average Chicagoans, however, pretty much just had to learn to live with the smog and smoke until Mayor Richard J. Daley pushed through strong air pollution controls in 1958 and throughout the 1960s.

In 1952, a Tribune reporter named Ruth Moss wrote a series of articles about the everyday experience of living with Chicago’s air pollution. She logged 50 miles walking around the city and suburbs wearing a white coat, which invariably became filthy, to demonstrate just how bad the air really was. In her final analysis, Moss determined that thanks to the dirty air, Chicago area residents spent $45 million a year on cleaning laundry, had 162,700 tons of dust fall on them and were shortchanged of 40 percent of their share of sunlight – and probably some years off their lives (Here’s her final article in the series.).

In his book “City of the Century,” Donald Miller makes frequent mention of a group of people who migrated to Chicago from Kentucky. One group lived in Buena Park; another settled on the West Side along Ashland Avenue. Can you tell us more about their stories?

–Peter Donalek, Buena Park

Ashland Avenue circa 1890

Ashland Avenue circa 1890

We often hear about settlers who rushed to Chicago in the mid-1800s to make fortunes in real estate, most from the East Coast, but there was also a group from Kentucky that got into the action here and became rich and politically powerful. So many of them settled on the Near West Side around Union Park that the area along Ashland Avenue and Washington Boulevard became known as the “Kentucky Colony.” In fact, Ashland Avenue itself is named for the Kentucky home of statesman Henry Clay.

One Kentucky colonist was future five-term Mayor Carter Harrison, a descendant of the same southern aristocratic family that gave us two U.S. presidents and whose son Carter Jr. went on to become a five-term mayor of Chicago himself (and was the first mayor actually born in Chicago). Today there’s a statue honoring Mayor Harrison the elder in Union Park (though its plaque is long gone). Harrison and others from the Bluegrass State were following the lead of Henry Honore, the son of a Kentucky plantation owner who moved here after a visit in 1853. Honore’s daughter Bertha married the millionaire Chicago merchant Potter Palmer and became the queen of Chicago society and a great civic leader. One more note about Carter Harrison Jr.: In 1919, he wrote a reminiscence of his youth in the so-called "Kentucky Colony" for a collection of stories about young Chicago.

Another Kentucky colonist, Edward Waller, helped finance some of Chicago’s first skyscrapers including the Home Insurance Building, the Monadnock and the Rookery. Clout from their neighbor Mayor Harrison helped, according to historian Donald Miller. Waller was a great benefactor of Frank Lloyd Wright’s, commissioning a number of projects from him including the low-income Edward C. Waller Apartments west of the Kentucky Colony. It’s now a Chicago landmark.

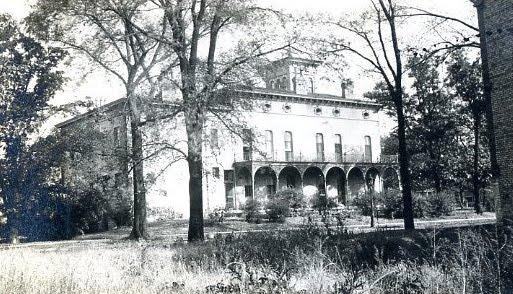

Buena House

Edward Waller’s brother, James, started a Kentucky settlement on the North Side when he bought a parcel of wooded land in what is today the lovely neighborhood of Buena Park, along Lake Shore Drive between Montrose and Irving Park. In 1861 James built a magnificent country mansion there that he called Buena House. Waller and his wife Lucy often entertained at Buena House with extravagant gatherings that were the embodiment of Southern hospitality. They even took in families whose homes were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871. Over the years, James and one of his children, Robert, developed Buena Park into a tony suburb full of beautiful homes, some of which are still there, like the mansion at 800 W. Buena, now the Menomonee Club.

Buena House

Edward Waller’s brother, James, started a Kentucky settlement on the North Side when he bought a parcel of wooded land in what is today the lovely neighborhood of Buena Park, along Lake Shore Drive between Montrose and Irving Park. In 1861 James built a magnificent country mansion there that he called Buena House. Waller and his wife Lucy often entertained at Buena House with extravagant gatherings that were the embodiment of Southern hospitality. They even took in families whose homes were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871. Over the years, James and one of his children, Robert, developed Buena Park into a tony suburb full of beautiful homes, some of which are still there, like the mansion at 800 W. Buena, now the Menomonee Club.

One of Buena Park’s residents, the beloved children's poet and journalist Eugene Field, wrote his most famous poem, “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” in 1889 while renting a house from the Waller family. He also wrote a poem set in the vacant lot next door called “The Delectable Ballad of Waller Lot.”

One passage reads:

“There children play in daytime

And lovers stroll by dark

For ‘tis the goodliest trysting-place

In all [of] Buena Park.”

My mother worked in the area of the U. of C. campus back in the '40s. She is trying to recall the name of a pediatric hospital in the Jackson Park neighborhood. Any ideas?

–Lisa Swetlik

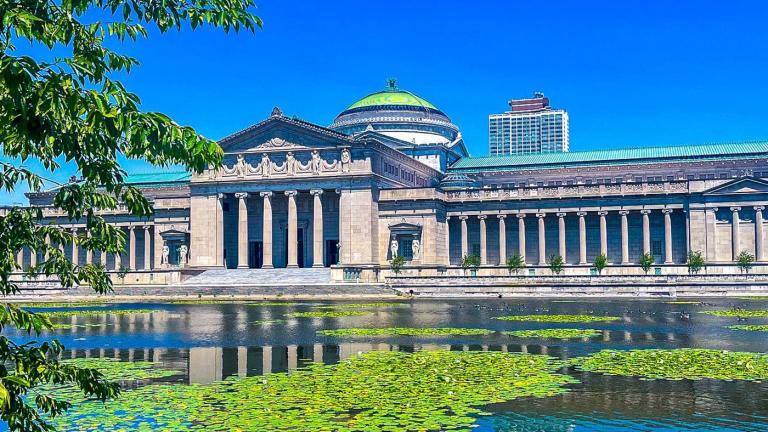

The pediatric hospital in Jackson Park is La Rabida Children’s Hospital, and it’s still there. Today, it’s a place where children with chronic medical conditions like asthma and cerebral palsy or who’ve suffered child abuse or other traumas can get treatment regardless of ability to pay. And, its Mediterranean-style architecture and its location on a spit of land between Lake Michigan and Jackson Park Harbor are clues to its interesting history.

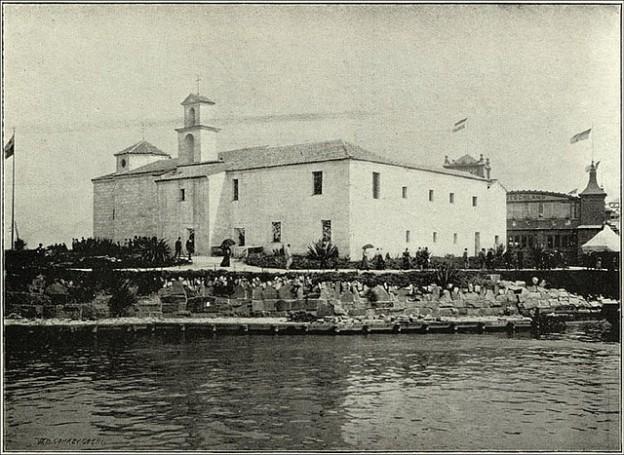

La Rabida Friary

La Rabida Friary

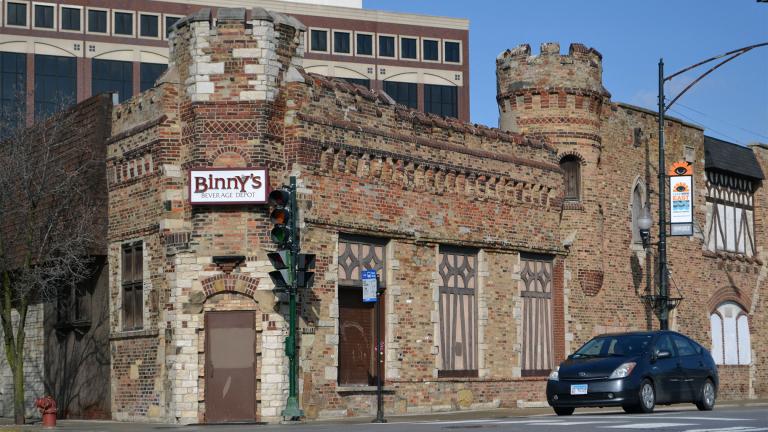

The current building dates from 1932 but it stands on the site of the Spanish Pavilion from the World’s Fair of 1893. That pavilion was a replica of a 13th century Spanish monastery called La Rabida. The La Rabida Friary is where Christopher Columbus set off in 1492 to sail the ocean blue, so it was a natural choice for the Columbian Exposition, which celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s trip across the Atlantic (one year late). When the fair closed, Spain donated the building to Chicago with the suggestion that it be used as a fresh air sanitarium for sick children.

It opened for its first full season in 1898 staffed by volunteers, mostly women. The sanitarium’s first focus was providing food, safe milk, water, fresh air and medical care to Chicago’s poorest children, who often got sick from spoiled food or milk. The hospital later specialized in battling childhood rheumatic fever, including one patient viewers might recognize – actor Joe Mantegna. In the 1960s, La Rabida expanded to its present-day mission.

As for the building, like most World’s Fair buildings, the original La Rabida wasn’t built to last. It was used until 1918, when the building was condemned. Most of it burned down in 1922. Patients were treated at other facilities until the pavilion was replaced 10 years later. The 1932 building has had a few additions over the years, the most recent being in 2013, but details like the tiled roof retain some of the original building’s Spanish character.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.