Chicago police Superintendent David Brown speaks during a virtual City Council hearing on Tuesday, Dec. 22, 2020. (WTTW News via City of Chicago)

Chicago police Superintendent David Brown speaks during a virtual City Council hearing on Tuesday, Dec. 22, 2020. (WTTW News via City of Chicago)

As furious aldermen demanded answers on Tuesday about the February 2019 raid that left a Chicago woman handcuffed and naked, Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown said he would tighten the rules governing the department’s use of search warrants.

The at-times contentious hearing started shortly after Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced she had tapped retired Judge Ann Claire Williams to conduct an outside investigation into the raid and the way the mayor’s office, the city’s Law Department and the police department handled the raid and its fallout, which touched off a political firestorm.

The rare Christmas-week City Council hearing came a week after video of the raid obtained by CBS2-TV showed Anjanette Young, a social worker, telling seven male police officers 43 times they were in the wrong home and begging them to let her get dressed.

Brown said there was “no excuse” for the conduct of the officers. All 12 officers involved in the raid were stripped of their police powers and assigned to desk duty by Brown on Monday. Brown told aldermen that his action was “warranted.”

Since the furor began, Lightfoot has touted the changes she made to the police department’s use of search warrants in January 2020, including a requirement that a supervisor sign off on the request and that information from a paid informant be corroborated before being used in a request.

“It is clear we still have significant work to do,” Brown told aldermen during the seven-hour hearing.

Brown said he would ban the department from seeking and executing “no-knock” warrants — which allow officers to enter a home or business without announcing themselves first — except in cases when someone’s life is at risk.

The officers who searched Young’s home did not have a no-knock warrant, Brown said.

In addition, Brown said officers would get additional training to ensure that they respect “human rights” and preserve the “dignity” of those present during a search, including those who belong to “vulnerable populations.”

Before a request for a warrant is presented to a judge, it must be approved by a deputy chief or an officer of higher rank, Brown said. In addition, that warrant can no longer rely on information provided by an informant paid by the department for information, he said.

Lieutenants — or higher-ranking officers — must be present at every search authorized by a warrant, Brown said.

Brown also promised to begin tracking data about search warrants. The department does not track searches conducted in a location not listed on the warrant, although those incidents trigger an investigation.

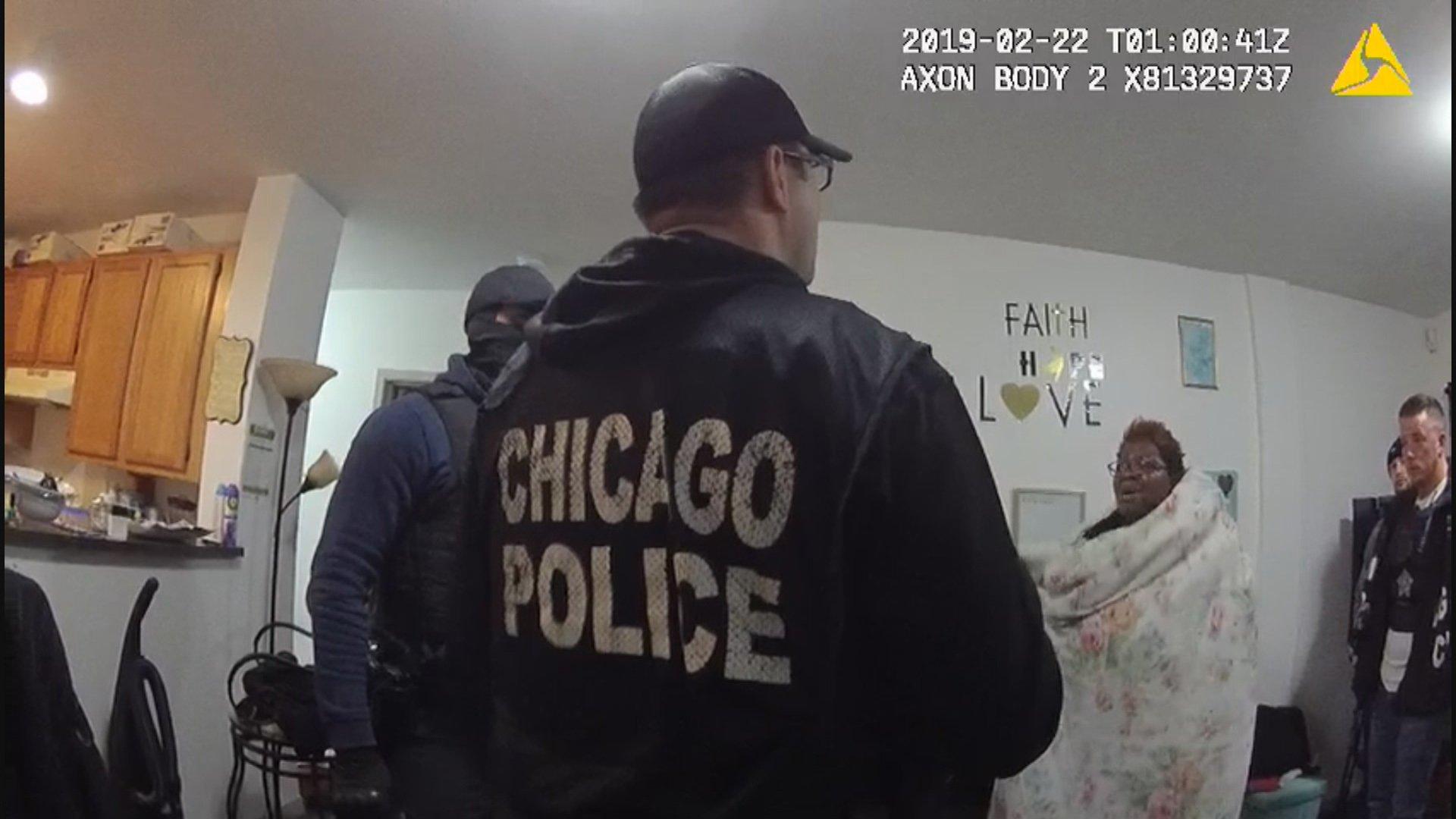

A still image from a Chicago Police Department body camera video shows a police raid at the home of Anjanette Young in February 2019. (WTTW News via Ja’Mal Green)

A still image from a Chicago Police Department body camera video shows a police raid at the home of Anjanette Young in February 2019. (WTTW News via Ja’Mal Green)

The lack of data has complicated efforts by Inspector General Joseph Ferguson’s office to investigate the issue of botched raids, said Deborah Witzburg, the deputy inspector general for public safety.

However, Witzburg said her office had sent preliminary recommendations for changes to Brown and other police leaders because of the pressing need for changes.

However, few — if any — aldermen seemed satisfied with the changes announced by Brown.

Elected to the City Council in 2007, Ald. Pat Dowell (3rd Ward) said she is all too familiar with the rhythms of a major police scandal. Under the bright media spotlights, top police brass come before aldermen, promise to adopt new policies and address the issues. But they are not directly responsible, and cannot address whether officers should be disciplined.

“We’ve heard this before,” Dowell said.

In several cases, Brown and his command staff could not answer the questions posed by aldermen.

That infuriated Ald. Jeanette Taylor (20th Ward), who referred to Brown as his staff as “professional time-wasters.”

Ald. Stephanie Coleman (16th Ward) responded succinctly when Brown did not know whether the commander of the district that included Young’s home at the time of the raid knew about the search before the warrant was served.

“This is bulls—,” Coleman said.

Public Safety Committee Chair Ald. Chris Taliaferro (29th Ward) admonished Coleman for using profanity.

Other aldermen said they were frustrated that there was no one present during the hearing from the mayor’s office or the Law Department.

Ald. Leslie Hairston (5th Ward) said the disproportionate number of search warrants served on the South and West sides was clear evidence of systemic racism and bias in the Chicago Police Department.

“You have to do better,” Hairston said. “You cannot do these baby steps.”

Ald. Matt Martin (47th Ward) said what happened to Young during and after the raid represented an “institutional failure” and stands as an “indictment” of the city’s public safety system.

“Our institutions are failing,” Martin said.

Ald. Andre Vasquez (40th Ward) asked Brown whether any of the officers present during the raid alerted their supervisors about the way Young was treated. Brown said none did.

“I am beyond angry about that,” Vasquez said.

Civilian Office of Police Accountability Chief Administrator Sydney Roberts also faced pointed questions about why the agency has not completed its investigation into the raid, which investigators began probing in November 2019 after Young sued the city.

Three times, Roberts told aldermen that the pace of investigations is determined by the agency’s staffing level. COPA has 1,854 outstanding complaints, including 900 that allege police conducted an improper search or seizure, Roberts said.

It takes COPA an average of 20 months to complete an investigation, Roberts said.

Roberts told aldermen that COPA, which is charged with investigating police misconduct, had struggled to pursue investigations during the coronavirus pandemic and amid the deluge of complaints about officers’ conduct during the anti-police brutality protests that followed the death of George Floyd on May 25 in Minneapolis police custody.

“I should have done a better job during COVID, during the pandemic to ensure that this case stayed on the radar,” Roberts said.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]