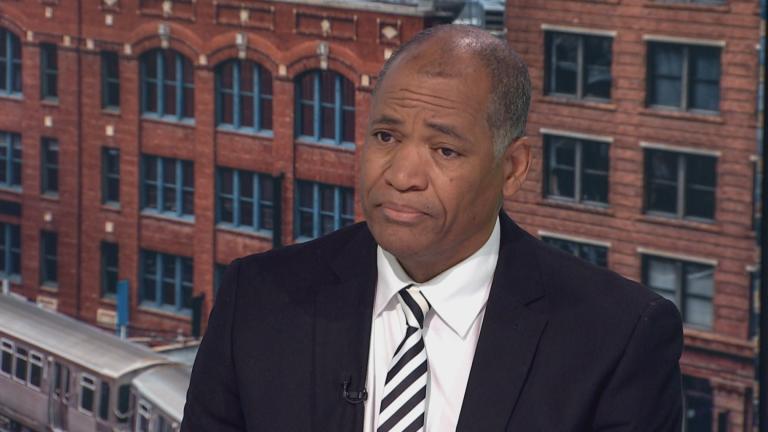

For young Black boys and men, Chicago can be a cradle and a crucible, a place where they can encounter both endless inspiration and endless despair. In the latest installment of our “Black Voices” Book Club, author Keenan Norris moves back and forth in time, drawing connections between the experiences of literary giants and those of his own father as a young Black man in Chicago in the book “Chi Boy: Native Sons and Chicago Reckonings.”

“My father gave me a number of books to read when I was 13 years old,” Norris said. “He gave me James Baldwin’s ‘Go Tell It on the Mountain.’ He said, ‘Read this, and you’ll know more about who I am.’ He gave me Richard Wright’s ‘Native Son’ when I was 14 years old and said, ‘Read this, and you’ll know more about where I’m from.’ So really Richard Wright’s ‘Native Son’ and then ‘Black Boy,’ Wright’s memoir, the full title of which is actually ‘American Hunger’ — those two books which my father gave me in this kind of preparatory, at-home African American literature course that I grew up with, it became really definitional for me, they help to illustrate for me some truths.”

Norris said while his book has its genesis in his father’s Chicago childhood, through writing “Chi Boy,” Norris hoped to illustrate more about Chicago’s place in the country’s history for Black Americans.

“I was drawn to write about Chicago because of my father’s stories, my father’s impact on me, the stories that my father told me about growing up in Chicago, and my larger fascination with the Great Migration,” Norris said. “I came to understand Chicago as particularly important in the history of Black America and our larger American narrative.”

Read an excerpt from the book below.

“Chi Boy: Native Sons and Chicago Reckonings" by Keenan Norris.

“Chi Boy: Native Sons and Chicago Reckonings" by Keenan Norris.

In Grant Park I sat where Barack Obama stood when he accepted the nomination to the presidency for the first time. I heard an old song blaring from a battered boombox balanced on the roots of a shade tree, I want to be free as the spirits of those who left. I walked the park. Nearer the river, I hadn’t been able to feel my face it was so fiercely cold, but now, further from its icy reach, I unfroze and felt everything. The cold had gotten past my layers and was in me, making me live in time and place. I looked down, at my hands, chalky white over dark brown skin, and at my shoes pounding forward: The dead white and brown grasses had already been padded away by a million feet before mine and had turned a consistency as fine as dust. I thought about all my family’s life that had happened here in this city. It is all gone, everybody, to wherever death goes when it takes us. Death has taken Butch Norris. It has taken Butch’s parents, my gramps with his penchant for war novels and war in the streets, and my granny, with her hushed and silenced dreams. It has taken Londa and Linda and Steph, Butch’s three sisters. It has taken my cousin, strangled to death in a drug deal gone bad in California on New Year’s Day 2016, which happened to be the first day of what would become Chicago’s most lethal year in two decades. Everything that was in me gave and tore away and I wandered, heading nowhere, a child lost in the city.

The term “Chi-Raq” links Chicago street violence to an infamous American war on the other side of the world. In thinking about the violence that has beset my own family, I’ve had to sink deep into the ways American street violence and American militarism are connected. I’ve had to think hard about my family’s most difficult days and about Chi-Raq as something other than a rap song or media hype or the nonsense we tell ourselves about people we fear, but instead as a story that does not even know itself.

Excerpted from “Chi Boy: Native Sons and Chicago Reckonings" by Keenan Norris. Copyright © 2023 by Keenan Norris. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.