The endangered rusty patched bumble bee. (Courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The endangered rusty patched bumble bee. (Courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Four years after the rusty patched bumble bee was placed on the endangered species list, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has released its final recovery plan for the insect, a plan critics say manages to go too far and yet not far enough at the same time.

Since evidence first emerged a decade ago of the precipitous decline of the rusty patched bumble bee (scientific name, Bombus affinis), now found in just 13% of the range it inhabited as recently as the 1990s, the bee has become emblematic of the perils facing pollinators, including climate change and habitat loss.

The federal recovery plan — not a regulatory document, but more of a road map on how to help a species reach the point at which it can be de-listed — addresses those issues, among others, in broad strokes. Recommended actions include minimizing the risk of disease and educating the public about ways the average person can made a difference (see sidebar, below). Fish and Wildlife pegs the cost of recovery at $16 million (barring any expensive land acquisition) and estimates a de-listing date of 2061 “if all actions are fully funded and implemented,” conceding it could take longer.

“Saving a species from extinction is a group effort, with partners from national conservation organizations and agencies to local communities and citizens, we can’t do this alone” Charlie Wooley, Fish and Wildlife regional director for the Great Lakes, said in a statement. “Together we can make sure this important native pollinator doesn’t slip away.”

Though the plan, on paper, sounds like a wraparound, all-hands-on-deck approach, it lacks teeth, said Lori Ann Burd, environmental health director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

It’s like the first Earth Day, Burd said, when the focus was on putting a stop to littering instead of putting an end to fossil fuels.

“A species that’s been around for millions of years is in a death spiral. That tells us something is horribly wrong,” said Burd. “For me, the biggest thing that jumps out is there’s one threat.”

That threat is pesticides, she said.

“There’s climate change and urbanization and extreme weather, but habitat that’s not deadly toxic is the very first thing,” Burd said. “What (the bees) need is non-poisonous habitat. None of this plan can work if habitat is still toxic. Nothing can follow until that threat is addressed.”

The recovery plan’s guidance to “minimize exposure to harmful pesticides” doesn’t come close to the outright ban conservationists have demanded, specifically of a class of chemicals known as neonicotinoids.

Neonicotinoids are widely used to treat agricultural crops and ornamental plants. They can be sprayed on foliage or injected into tree root zones or trunks, but are more often used to coat seeds. The chemicals were introduced in the 1990s, a time frame that many people, Burd included, link to the decline of pollinators such as the rusty patched bumble bee.

The European Union has banned several neonicotinoids, yet the U.S. has allowed them to remain on the market while the EPA studied the pesticides’ impact on endangered species. Draft biological evaluations were recently released by the agency, finding several of the chemicals “likely to adversely affect certain listed species or their designated critical habitats.” The agency is still accepting public comments on the evaluations through Oct. 25.

Those results should have prompted tougher language from Fish and Wildlife, and an opportunity was lost in not singling out pesticides, Burd said. While the agency itself can’t implement a ban, it could use its soft power in other ways.

Fish and Wildlife could declare, “We’re going to take this on,” she said, and pull all the levers at its disposal, such as ensuring federal lands are managed without pesticides, providing grants to farmers to grow organic crops, leaning on the USDA, conducting an outreach campaign to state agencies, and more.

“There are options that just take political will,” said Burd.

Nearly a year into the Biden administration, there’s been no indication that will exists, she said, noting that Fish and Wildlife still, “alarmingly,” lacks a director.

“Maybe there’s been nicer rhetoric, but we haven’t seen any significant course correction yet,” Burd said. “If this administration wanted to turn around the pollinator crisis, they could. But nothing makes us overly optimistic.”

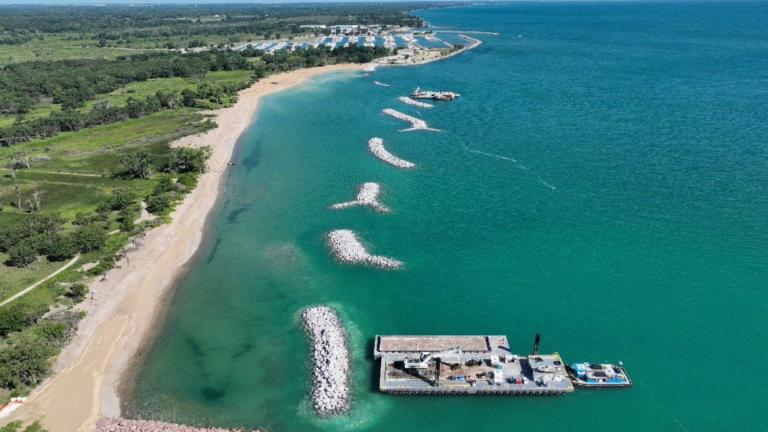

The range of the rusty patched bumble bee. Historic range in gray, currently likely to be present in red, unlikely presence but important for conservation in yellow. (Courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The range of the rusty patched bumble bee. Historic range in gray, currently likely to be present in red, unlikely presence but important for conservation in yellow. (Courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Bombus affinis is one of some 50 species of bumble bees native to North America. Its range extended across 28 states from Maine to the Dakotas, dipping as far south as upper Geogia and north along the Canadian border.

As pollinators go, Bombus affinis is a generalist and fairly adaptable. It doesn’t require pristine habitat and it’s not a picky eater, in that it doesn’t rely on a single flower to survive the way some pollinators do.

But when Sydney Cameron, an entomologist at the University of Illinois, led a study more than a decade ago into the status of native bees, she discovered affinis was a species on the ropes, its presence now confined largely to pockets of Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. The findings of Cameron’s research raised the alarm that ultimately resulted in the endangered species listing, making affinis the first bee in the continental U.S. to receive the designation.

Her response to the recovery plan is complicated. Cameron is a scientist, she emphasizes, not a conservationist or a politician. Some of the plan is good, she said, particularly around habitat management and protection, but she finds other parts problematic and the science lacking.

Apart from research conducted in the 1930s, which focused on the bumble bee’s nests, the file on Bombus affinis is thin. “We’re talking about very spotty studies over the last 100 years,” she said.

What do we know about historic pathogen loads? she asked. Or the pollen affinis collected, from which flowers, where and when? Past response to pesticides?

More research needs to be done before drawing conclusions and charting a course to recovery.

Cameron agrees neonicotinoids could bear some of the responsibility for the bumble bee’s sharp decline, but there’s also a well-documented pathogen to consider, Nosema bombi, whose spread has been unintentionally aided by the transport of bees cross-country by commercial pollinator enterprises. How has the interaction between the two, pathogen and pesticide, affected affinis specifically? Because some bumble bees are still thriving under similar conditions.

“You can’t put a whole package together without knowing what’s important or not,” Cameron said. “Has it been studied?”

Her primary quarrel with the recovery plan is an action item that calls for management of the affinis population by creating an “insurance” population in the lab and then potentially reintroducing these bees into the eastern areas of affinis’ former range.

This is not only a difficult proposition — “Breeding bumble bees is an art, not a technology,” Cameron said — but a risky one in that it would require the capture of queens.

“If you’re not successful, you’ve sacrificed some of the few queens left,” she said. “Trying to play god is just a stupid idea.”

Cameron, who is retiring is December, trusts there are entomologists who will do the hard science needed to better understand affinis and what the species needs to survive. But, like Burd, she questions whether policymakers will follow through when it comes to tough decisions about regulating the domestic bee industry or banning pesticides.

The stakes are too high, and not just for Bombus affinis, to act with timidity.

“If we allow (affinis) to go extinct, the pattern is going to amplify itself,” Cameron said. “It’s one species, yes, and it won’t change the world, but when you put it all together, it starts to get scary.”

DO TRY THIS AT HOME

Though it seems counterintuitive, urban areas have more bee diversity than their rural counterparts, where monocultures of crops like corn and soybean dominate. Chicago, in particular, has been a leader in encouraging the sorts of pollinator gardens that insects like the rusty patched bumble bee need to thrive, said Sydney Cameron, an entomologist at the University of Illinois.

Incorporating pollinator-friendly plants into landscaping, especially plants that bloom at different times of the year, will help the rusty patched bumble bee. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Incorporating pollinator-friendly plants into landscaping, especially plants that bloom at different times of the year, will help the rusty patched bumble bee. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Here are five things people can do to help the rusty patched bumble bee (and other native bees) in their own yards:

— Plant native flowers or those labeled “pollinator friendly,” with an eye toward mixing species that bloom at different times of the year. This will maintain a steady source of food for bumble bees.

— Leave dandelions alone. The rusty patched bumble bee will feast on dandelions in the spring before other flowers are in bloom.

— U.S. Fish and Wildlife advises people to be “conservative” with pesticides, using only when necessary, and only as directed. Cameron goes a step further and says, “Stop using pesticides. You don’t need a perfectly green lawn.”

— Keep a “messy” lawn in the fall. Rusty patched bumble bee queens spend the winter in loose plant material on the surface of the ground.

— Look for nests. Rusty patched bumble bee nests are underground, one to four feet below the surface.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]