Babbling baby bats. Simulated rats. The impressive memory of cuttlefish. And why, counter to popular belief, some key mental abilities appear to actually improve with aging.

University of Chicago paleontologist Neil Shubin returns to help us understand some of the latest science stories making headlines.

Babbling Baby Bats

Researcher Ahana Fernandez at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama has found that baby bats share a unique trait with human babies – they babble.

Fernandez found that just like human babies, sac-winged bats (Saccopteryx bilineata) babble as they begin to learn language.

“Aside from humans, S. bilineata is the only mammal known to display babbling behavior and vocal imitation,” according to a statement announcing the discovery.

It is hoped that the research may shed light on the evolution of human language.

Mother and pup of the bat species Saccopteryx bilineata. Similar to human infants, pups begin babbling at a young age as they develop language skills. (Courtesy Ahana Fernandez / Michael Stifter)

Mother and pup of the bat species Saccopteryx bilineata. Similar to human infants, pups begin babbling at a young age as they develop language skills. (Courtesy Ahana Fernandez / Michael Stifter)

Cuttlefish Memory

An international research team has found that cuttlefish retain sharp memories of specific events even into old age.

“Cuttlefish can remember what they ate, where and when, and use this to guide their feeding decisions in the future. What’s surprising is that they don’t lose this ability with age, despite showing other signs of ageing such as loss of muscle function and appetite,” said first author Alexandra Schnell of the University of Cambridge’s Department of Psychology, who conducted the experiments at the Marine Biological Laboratory In Woods Hole, Mass in collaboration with MBL Senior Scientist Roger Hanlon.

The research is said to be “the first evidence of an animal whose memory of specific events does not deteriorate with age.”

An international research team has found that cuttlefish retain sharp memories of specific events even into old age. (Courtesy Grass Foundation)

An international research team has found that cuttlefish retain sharp memories of specific events even into old age. (Courtesy Grass Foundation)

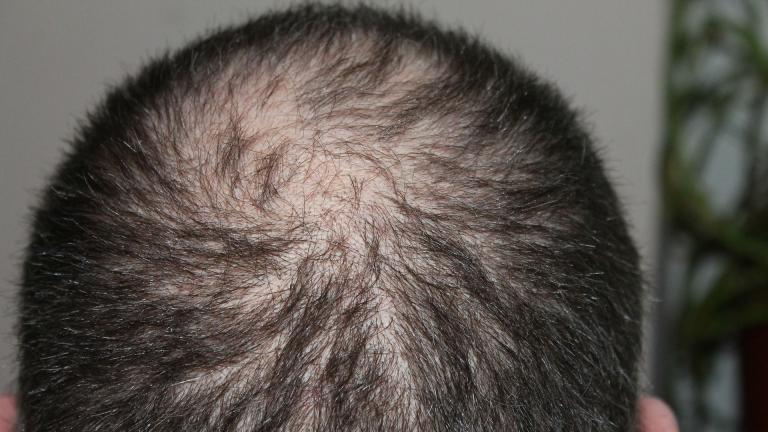

Key Mental Abilities Actually Improve with Aging

It has long been assumed that as we enter old age our mental abilities decline but researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center have discovered evidence that counters that view.

The researchers found that two key brain functions that allow people to attend to new information and to focus on what’s important in a given context improve in older individuals.

“These results are amazing, and have important consequences for how we should view aging,” said the study’s senior investigator, Michael T. Ullman, PhD, a professor in the Department of Neuroscience, and Director of Georgetown’s Brain and Language Lab.

“People have widely assumed that attention and executive functions decline with age,” said Ullman. “But the results from our large study indicate that critical elements of these abilities actually improve during aging, likely because we simply practice these skills throughout our life.”

Rat Whisker Simulation

Engineers at Northwestern University have developed the first three dimensional simulation of a rat’s complete whisker system.

Rats are able to extract detailed information from their environment using their whiskers “including an object’s distance, orientation, shape and texture,” according to a news release detailing the research. “This keen ability makes the rat’s sensory system ideal for studying the relationship between mechanics (the moving whisker) and sensory input (touch signals sent to the brain).”

Researchers created a virtual model of a rat’s whiskers because it’s currently impossible to do comparable studies with real animals.

“We cannot measure the signals at the base of a real rat’s whisker using current technology because, as soon as you embed a sensor, it interferes with the signals themselves,” said Northwestern’s Mitra Hartmann, the study’s senior author. “The only way we can really capture a rat actively sensing its environment under natural conditions is to simulate it.”