University of Chicago paleontologist Neil Shubin is gearing up for his next expedition.

The long-delayed trip is a return to the Canadian Arctic and an area where Shubin made a career-defining discovery back in 2004.

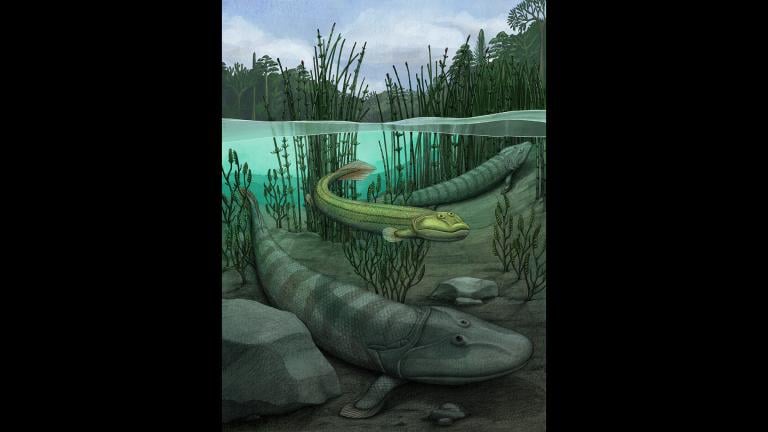

That was when Shubin and his team found Tiktaalik, a so-called “missing link” fossil of one of the first creatures to emerge from the water onto the land about 375 million years ago.

Shubin said he is “totally stoked” to finally be returning after a four-year delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The whole idea is to find places around the world that have rocks of the right age and the right type to answer the question that you’re interested in,” said Shubin. “In this case, the question I was interested in was the transition from fish to land-living animals. Well, if that’s your approach, it becomes this global Easter egg hunt because you pull out maps, you pull out scientific papers and you try to find the different places in the world that can answer the question that you’re interested in.”

That hunt has seen Shubin conduct fieldwork in North America (including Greenland), China, Africa, Antarctica — and of course, the Arctic.

“One of the great joys about doing this research is we’re going to places nobody has walked before,” said Shubin. “So we find very little evidence of human impact there, which makes it really special. For me, the absolute most exciting part is dropping on a new place for the first time seeing the rocks and trying to figure out where the treasure is going to be.”

Shubin uses geological survey maps to identify the best areas to hunt for fossils of the right age to shed light on critical transitional moments in evolutionary history. His upcoming expedition in July aims to find more transitional species contemporaneous with Tiktaalik.

“These rocks were formed in ancient rivers and streams,” said Shubin. “What we’re looking for is the diversity of fish that are living in these environments, which are about 375 million years old — about the same age as Tiktaalik — but a different sort of environment. We’re looking for the same transition, but just Tiktaalik 2.0 or Tiktaalik 3.0.”

One method of examining the fossils even if they are still encased in rock is to use a CT scanner to create three-dimensional digital images.

“We can look inside a fossil,” said Shubin. “You can scan every single bone of Tiktaalik or any critter and then put it together digitally using computer programs that people use to design video games. And then you can see it in a whole new way. You can look inside the bones, the joints, and you can print these out on 3D printers. So the digital piece really changes what we do. We can begin to visualize how Tiktaalik actually swam, how it walked, how it moved about.”

But Shubin’s research doesn’t only entail examining fossils. His lab at the University of Chicago is also conducting genetic research to help try to unravel the mysteries of evolution.

“What we look at is DNA,” said Shubin. “And we look at embryos, and we ask the question: How does a living fish differ from a land-living animal like a frog or a mouse or a bird or a human? What’s different? What’s the same?”

Combining the insights derived from collecting fossils in the field and genetic research in the lab enables Shubin and his team to develop a more nuanced understanding of critical evolutionary developments.

“These are two different approaches to answer the same question: How did limbs arise from the fins of fish?” said Shubin. “The two approaches together really give us a much more complete answer than either one alone. … One of the really interesting discoveries is that many of the genes that were active to build our own hands and feet are active in the fins of fish, making the ends of the terminal ends of their fins. So part of the evolution of limbs from fins didn’t involve the origin of new genes. We have the same DNA. It’s really using the old DNA in new ways. It’s repurposing at the genetic level, which is really kind of profound.”