The Field Museum has more than 2 million fish in its research collections. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum has more than 2 million fish in its research collections. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Visitors can roam the Field Museum from open to close and still not have enough time to take in everything there is to see. And that’s just talking about the objects on display, which represent less than 1% of the Field’s vast holdings.

What the public rarely has access to are the tens of millions of specimens collected by the Field, not for exhibits but for scientific study. Many of these zoological and botanical specimens are housed in the Collections Resource Center, a purpose-built “bunker,” completed in 2005, buried under the south lawn of the Field’s lakefront campus.

“People think, ‘Oh, it’s that cool place for a field trip,’ not that it’s an active research facility,” said Kate Golembiewski, PR and science communications manager for the museum.

A short elevator ride separates the Field’s two identities, descending from the museum’s main floor down to the 186,000-square-foot collections repository, which is something of a cross between a warehouse and an archive, a library of life on Earth.

The Field Museum's underground Collections Resource Center. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum's underground Collections Resource Center. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field’s collections starred in their own exhibit, “Specimens,” in 2017, and have been back in the news recently for playing a key role in a study on the presence of microplastics in fish.

Tim Hollein, an associate professor of biology at Loyola University of Chicago, and his graduate student advisee Loren Hou suspected that microplastics were even more insidious in freshwater fish than previously thought. To prove their theory, they needed specimens of local species — and not just a largemouth bass here or a goby there — but samples of the same fish continuously collected throughout the last century up to the modern day.

They cold-called (actually cold-emailed) the Field, and ichthyologist Caleb McMahan, the museum’s manager of the fishes collections, was able to oblige.

(Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

(Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Perhaps best known in the scientific community for its concentration of tropical, deep sea and Indo-Pacific fish, the Field, given its location on Lake Michigan, also maintains a sampling of Great Lakes fish. Specimens are routinely added in order to provide a snapshot of a given fish at different points in time so that scientists can identify any changes, precisely the sort of project Hollein and Hou had in mind.

“These were collected to be used,” said McMahan. “What information can we extract from these fish?”

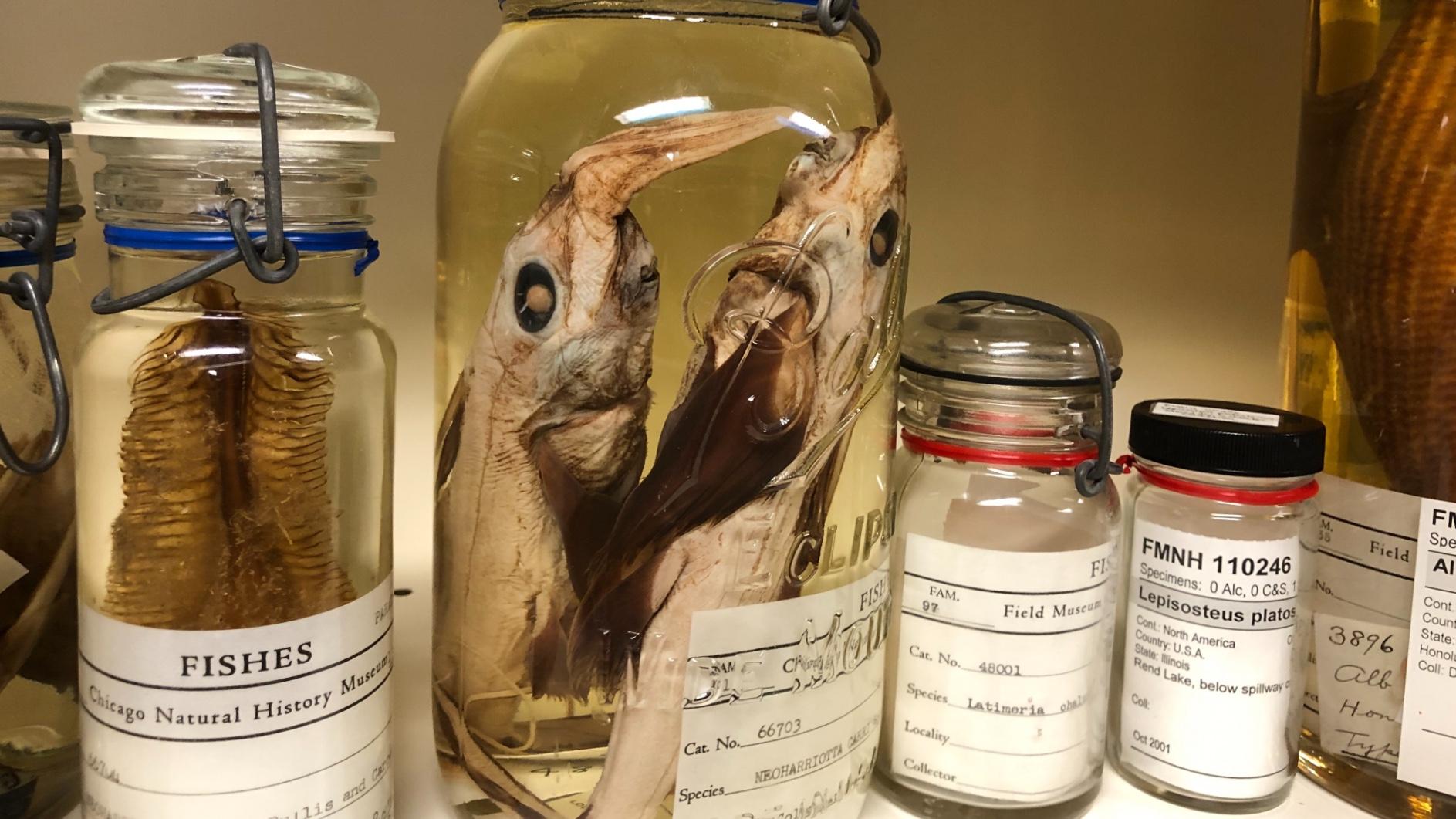

For Hollein, an aquatic ecologist who more typically studies water pollution, his first trip to the resource center was a revelation. There are shark skeletons hanging in lockers, spiked snouts of sawfish tucked away in flat file drawers, and row upon row of shelves laden with glass jars containing fish preserved in alcohol.

“I had an idea they had a lot of specimens, but I had never visited, I had never seen it,” he said.

Already, Hollein said, his visit to the center has sparked ideas for other studies the specimens could support, be it repeating the microplastic experiment on fish from other parts of the world or investigating the possible link between microplastics and a species’ diet.

“We don’t have a sense if more plastic is in predators versus plant eaters,” he said.

It’s tough to compete, in terms of sheer dramatic effect, with the dinosaur skeletons on display in the Field’s exhibit halls above ground, but the fish collection has its share of wonders.

Coelacanth specimen. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Coelacanth specimen. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

McMahan leads visitors to a nondescript metal container, flips the dozen or so latches holding the lid in place, and pops the top. There, buoyed by a bath of funky-smelling preservative, is a coelacanth specimen, one of five in the Field’s possession.

The fish was once thought to have become extinct 65 million years ago but was rediscovered in 1938. “It’s the fish equivalent of finding a T. rex,” he said.

The Field’s specimens are often used in anatomical research, said McMahan, as he wriggled the coelacanth’s fleshy, limb-like pectoral fin, which many scientists believe represents one of nature’s first takes on an arm.

The coelacanth also serves as a prime example of the difficulty ichthyologists face in declaring a species extinct. Who can say definitively what lurks in the oceans’ unknowable expanses or depths?

When scientists do make a rare discovery, “type specimens” like those in the Field’s collection are key to identifying whether a fish represents a new species, an evolution of an existing species, or a species long lost or forgotten.

Type specimens, McMahan explained, are the specimens on which the description of a species is based; they’re the reference point, the standard, in terms of defining features.

One such type specimen, Evarra tlahuacensis, is among the Field’s most prized. Though nothing much to look at — dung colored and just a couple of inches long — the minnow-like fish, collected in Mexico in 1901, is one of a kind.

“This specimen is the only way we know this species existed,” said McMahan. It’s never been found since, though McMahan is among those still looking.

Caleb McMahan, the Field Museum’s manager of the fishes collections, shows the snout of a sawfish. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Caleb McMahan, the Field Museum’s manager of the fishes collections, shows the snout of a sawfish. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Uses for the Field’s collection continue to change and evolve, and so does the process of collection itself.

Specimens were once labeled with the species of fish and the location and date where it was caught, and nothing else. Today, scientists will add detailed information about the surrounding habitat, be it stream flow, lake depth, vegetation or substrate, McMahan said.

Why a fish lives where it does is as important as its genetic makeup, particularly in light of climate change and for conservation purposes.

Imagine a nature preserve created only using the old school location data of “this fish, in this river.” What if the preserve’s boundaries don’t include the section of river with the habitat actually preferred by the fish? McMahan asked.

“Fishes live in bodies of water, but not homogeneously,” he said. “A lot are picky.”

Understanding a fish’s environmental parameters, now, will also assist tomorrow’s researchers, the people reading the labels decades or centuries from now. If a fish is no longer found where expected, scientists can question whether the temperature of the water changed, is it shallower or deeper, is a certain plant no longer present?

Fish can’t talk, but maybe someday their specimens will speak for them.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]