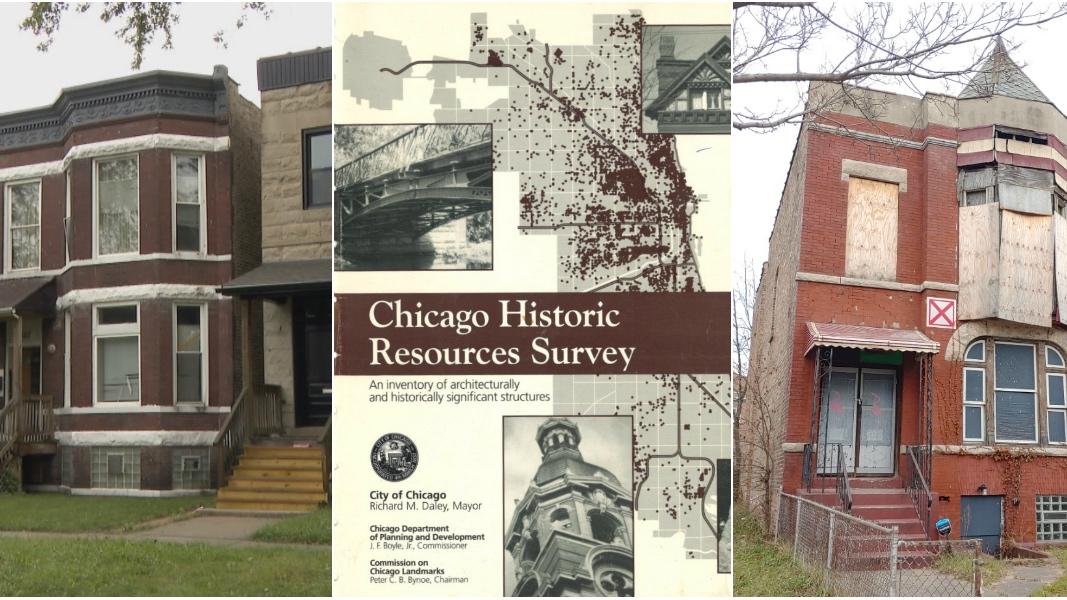

From left: Emmett Till’s childhood home (WTTW News), Historic Resource Survey cover (courtesy of Preservation Chicago), and Muddy Waters’ house (Ward Miller / Preservation Chicago).

From left: Emmett Till’s childhood home (WTTW News), Historic Resource Survey cover (courtesy of Preservation Chicago), and Muddy Waters’ house (Ward Miller / Preservation Chicago).

When Blake McCreight purchased the former home of Emmett Till and his mother Mamie Till-Mobley as a development opportunity a year ago, he had no idea of the property’s significance, McCreight told members of the Chicago Commission on Landmarks at a recent hearing to determine preliminary landmark designation for the Tills’ Woodlawn two-flat.

Even Commissioner Maurice Cox, head of the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, said he wasn’t aware of the location of the Tills’ house, despite the fact that Emmett Till’s murder, which ignited the modern civil rights movement, is ingrained in African American culture.

“I don’t think I knew where the house was,” Cox said during the hearing.

The oversight isn’t surprising. There’s nothing remarkable about the Till house, at 6427 S. St. Lawrence Ave., other than its one-time residents.

In the absence of any connection to a noted architect or any distinguishing design features, the Till home, like tens of thousands of other buildings in Chicago, failed to merit a mention in the city’s preservation “bible,” the Chicago Historic Resources Survey.

And that’s a problem, preservationists and historians say, particularly because the survey is often the only thing standing in the way of a building’s demolition. At any point in the past 60 years, the Till property could have been razed and a piece of important history lost without any alarm bells sounding.

‘No Tool Is Perfect’

The Chicago Historic Resources Survey was completed in 1995, the culmination of 12 years of field work and research that resulted in a catalog of 17,000 historic and architecturally important buildings, objects, structures and sites constructed prior to 1940.

It was an epic undertaking and the survey has been an invaluable tool for preservationists over the past 25 years.

But the criteria used to determine a building’s inclusion in the survey have recently been called into question. There is, for one, the simple fact that buildings constructed in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s — outside the survey’s scope — have since aged into the “historic” category. And then there’s the issue of whose history is being told when determinations are made regarding who or what is or isn’t significant.

Both of these points were raised earlier this month at the Landmark Commission meeting, which veered far off topic from its published agenda.

Architect Jonathan Solomon, an associate professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, opened the door to the discussion during his comments in support of a landmark designation for the Till home.

Solomon, a member of the team that prepared the Till landmark documentation, noted that sites of importance to the Black experience are underrepresented on the landmarks list, in part because of their absence in the survey, which in turn was conducted, he said, without the expertise of Black architects or Black preservationists.

“No tool is perfect,” said Solomon. “I ask my students to remain aware of the bias in their tools.”

Lisa Dichiera, director of advocacy with Landmarks Illinois, echoed Solomon’s comments.

“We need to think about ways to update that survey,” Dichiera said. It’s time, she said, to identify and protect buildings of the recent past as well as those with ties to social history, including those linked to the Black Panthers and Muddy Waters — ordinary buildings that tell extraordinary stories.

Inclusion in the resources survey can trigger a “demolition hold” on a property, but without that safety net for a building, a structure can all too easily fall through the cracks, Dichiera said.

Cox, who was appointed to his role in 2019 by Mayor Lori Lightfoot, acknowledged the survey’s deficiencies, and suggested that an accounting of sites of historic memory in Black and Latino communities was needed.

“We don’t have a record of the full extent of actual sites tied to the African American and Latino experience. I suspect that there are hundreds of sites and we don’t know where they are,” Cox said. “If we were to do a survey, at least when those properties change hands, owners will know what they’re getting into.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]