Twenty-five years ago, one of the deadliest events in Chicago history slowly unfolded: 739 Chicagoans — many of them poor, elderly and Black — died from heat-related causes over five days of intense and unrelenting heat in July 1995.

Today, as the slow-moving disaster of the coronavirus pandemic continues to unfold, author and sociologist Eric Klinenberg sees many parallels to the summer of 1995.

“This was a disaster … that targeted the most vulnerable people in the city,” said Klinenberg, who wrote the 2002 book “Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago” analyzing the heat wave and its aftermath. “African Americans were the most likely to die, the neighborhoods on the South Side and the West Side were hit disproportionately, especially neighborhoods that were depleted — places that had lost a lot of the population and commercial infrastructure, where people were kind of hunkered down at home rather than going out to into public places to get support.”

Klinenberg said that while the cause of the disaster was the weather, the overwhelming heat combined with of structural and social inequities — and an inadequate government response — made it an especially terrible week.

“This was not ordinary heat … it hit 106 degrees, the heat index felt like 126, and … what was really distinctive about that week was it didn’t get cool at night, it stayed up in the 80s, so there was nowhere for people Chicago could turn for relief, especially because the power went out in hundreds of thousands of homes. Couldn’t even turn on the AC,” he said.

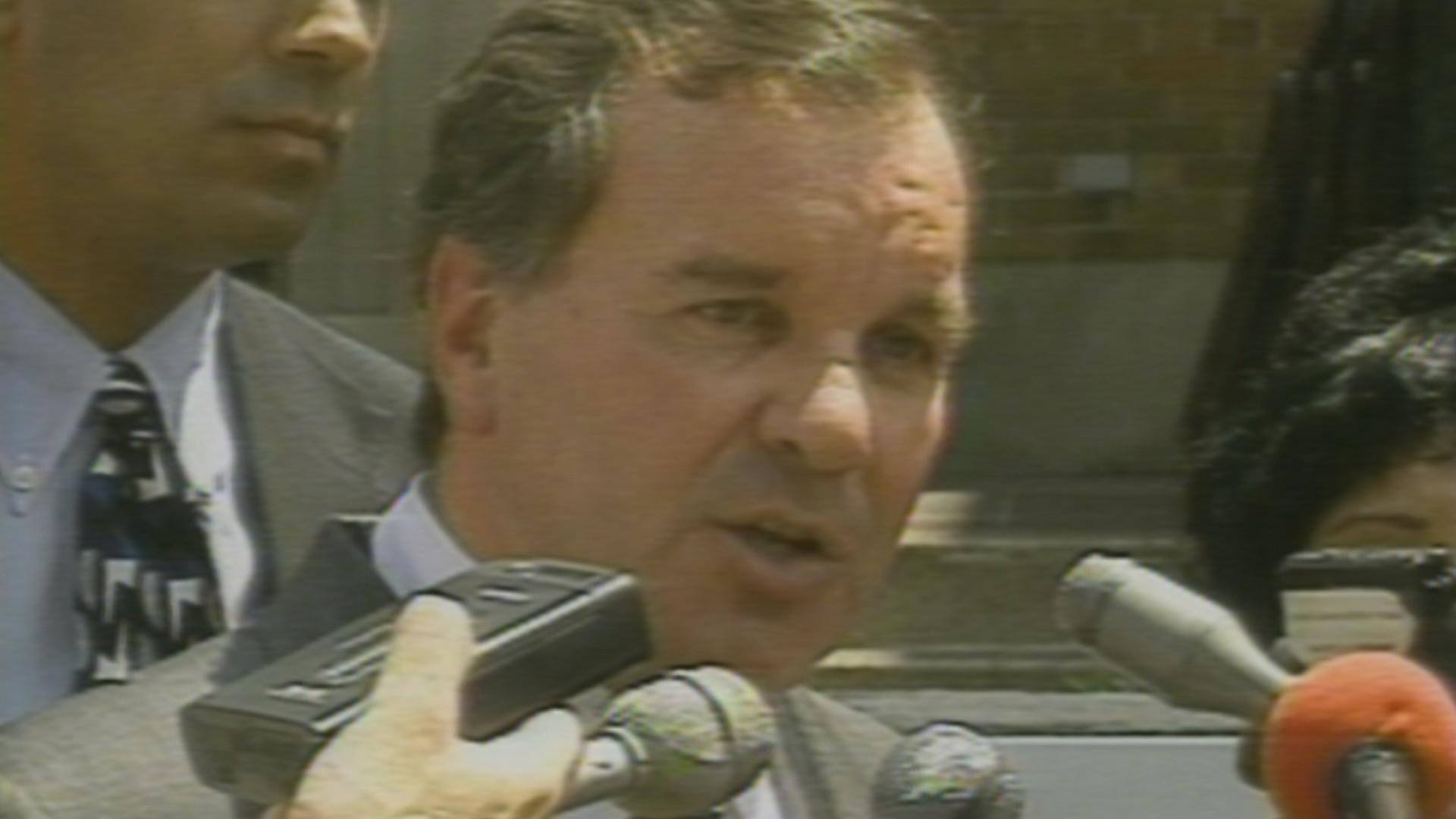

In 1995, then-Mayor Richard M. Daley publicly expressed skepticism as to whether the spike in deaths should be attributed to the heat wave, and his administration was slow to acknowledge the disaster and organize a response. Klinenberg sees similarities in the federal government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mayor Richard M. Daley shares his skepticism about heat-related deaths in the summer of 1995. (WTTW News)

Mayor Richard M. Daley shares his skepticism about heat-related deaths in the summer of 1995. (WTTW News)

“You could see the heat coming in advance, scientists were warning that it was going to be dangerous, the leadership in Chicago didn’t take it seriously,” he said. “When it became a deadly and dangerous situation, leadership tended to focus on managing the public relations problem rather than dealing with it as an urgent public health crisis … in the absence of leadership, the city broke down just as it’s happening now in the United States. In the absence of good leadership, our nation is failing to deal with this COVID-19 crisis.”

While the grim episode revealed the stark inequities across Chicago communities, in its aftermath the city greatly improved its response to public health crises.

“The city is now a leader when it comes to dealing with an acute heat emergency … It communicates more effectively, it works with local media,” said Klinenberg.

But many of the inequities that exacerbated the 1995 death toll persist today. Underserved, high-crime neighborhoods, isolated elderly residents and limited access to health services all contribute to the spread of COVID-19 across the city.

“It’s the underlying stuff that’s really difficult for Chicago,” Klinenberg said. “How’s the city going to deal with the profound economic inequality, the racial segregation, the social isolation? We’re seeing you can’t get out of these health problems just by dealing with the problem in the moment of the emergency. You have to take the underlying structure of the city seriously.”

Many of the neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of heat wave victims also have high concentrations of COVID-19 deaths, with one notable exception: the Latinx population, which has seen high rates of COVID-19 infections, had a much lower death rate than the Black population during the heat wave.

Klinenberg theorized that largely Latinx neighborhoods tend to have busy commercial districts, which offered more opportunities and spaces for cooling than the worst-hit Black neighborhoods, which lacked thriving business districts.

“In 1995, living in multi-generational households and having a lot of density was protective, of course this year in the coronavirus pandemic, living in a multi-generational household puts you at greater risk, so you really have to understand the sociology of these events to understand what’s going to happen,” he said.

A documentary based on Klinenberg’s book about the 1995 heat wave, called “Cooked: Survival by Zip Code” airs Monday at 10 p.m. on WTTW.