From the Picasso to the Bean to countless city murals, public art is a vibrant part of Chicago culture.

But for over a century, Chicagoans have taken special pride in a pair of sculptures watching over Michigan Avenue.

Geoffrey Baer tells us more about the Art Institute of Chicago’s lions.

What’s the history of the lions outside of the Art Institute?

– Marianne Morrison, La Porte, Indiana

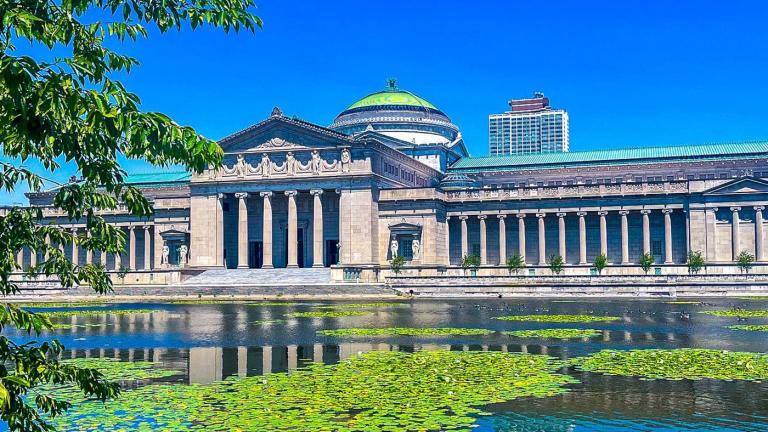

Like so many things in Chicago, the history of the lions can be traced back to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition – also known as the World’s Fair.

The original section of the Art Institute building, which the Lions guard, was itself built for the World’s Fair. It was the only structure to be constructed outside of Jackson Park and one of just a few that wasn’t destroyed when the fair ended.

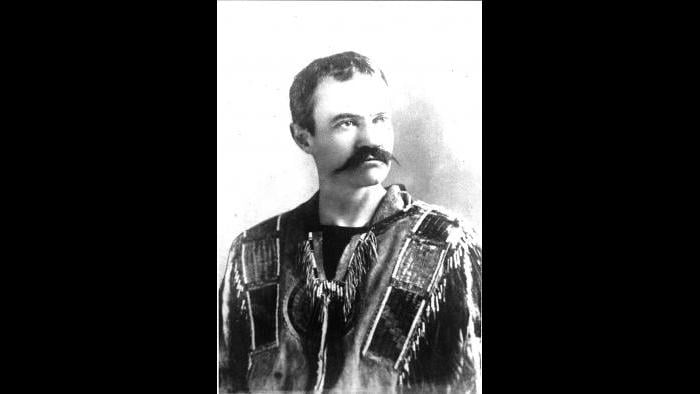

The building opened in 1893. But for almost a year, its front doors were left unguarded! The lions weren’t installed until May of 1894, designed by sculptor and then-Chicagoan Edward Kemeys.

Early days at the Art Institute of Chicago (Courtesy Chicago History Museum)

Early days at the Art Institute of Chicago (Courtesy Chicago History Museum)

By the late 1800s, Kemeys was the country’s premier “animalier” – a fancy French word that just means sculptor of animals.

Like many American artists of the time, Kemeys was drawn to scenes of raw and unfiltered nature. The Art Institute actually hosted an exhibition of his work in 1885 at its previous location, a few blocks south at Michigan and Van Buren in what is now the Chicago Club.

Kemeys ended up contributing a dozen sculptures to the World’s Fair in 1893 – more than any other American. Like much of the exposition’s “White City,” they were made of plaster, not made to last. That included two lions, as well as two other sculptures Chicagoans may recognize: the two bison which today stand in Humboldt Park, just north of Division Street.

But of course, it’s the lions that became Kemeys’ most visible work, seen by millions of people every year. When the World’s Fair ended, Florence Lathrop Page – an early benefactor of the Art Institute and sister-in-law of Marshall Field – commissioned and paid for Kemeys’ designs to be cast in bronze.

Each weights over 2 tons. And if you look closely, you’ll realize that they are not actually identical twins.

The north lion, left, and south lion at the Art Institute of Chicago. (Credit: Kim Scarborough / Wikimedia Commons; Heather Paul / Flickr)

The north lion, left, and south lion at the Art Institute of Chicago. (Credit: Kim Scarborough / Wikimedia Commons; Heather Paul / Flickr)

Kemeys wanted them to have their own personality and style. He styled the northern lion to be “on the prowl,” with its mouth slightly ajar and its eyes gazing in the distance.

Contrast that with the courage – or maybe even hubris – of the southern lion, which is modeled “in an attitude of defiance.” You can see that coming through in its body language – notice the upturned, regal head.

Over the years, the lions have become more than just statues – they’re almost mascots for the city.

Since their early days, the sort of “stoic realism” Kemeys was going for in his design has been greeted with a certain playfulness – like on the cover of this 1928 issue of The Chicagoan magazine.

More recently, the Lions have become diehard Chicago sports fans! Whenever a local team has a strong postseason run they’ll don hats for the Cubs or Sox, or helmets for the Bears and Blackhawks.

There’s also the annual “wreathing of the lions,” in which they are decked out in wreaths and bows for the holidays during an annual ceremony and performance of some kind.

Today, the Lions even have a Twitter account! They post semi-regularly, mostly about local sports and other bits of local culture – like the only proper way to make a Chicago hot dog.

(Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago)

(Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago)

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.