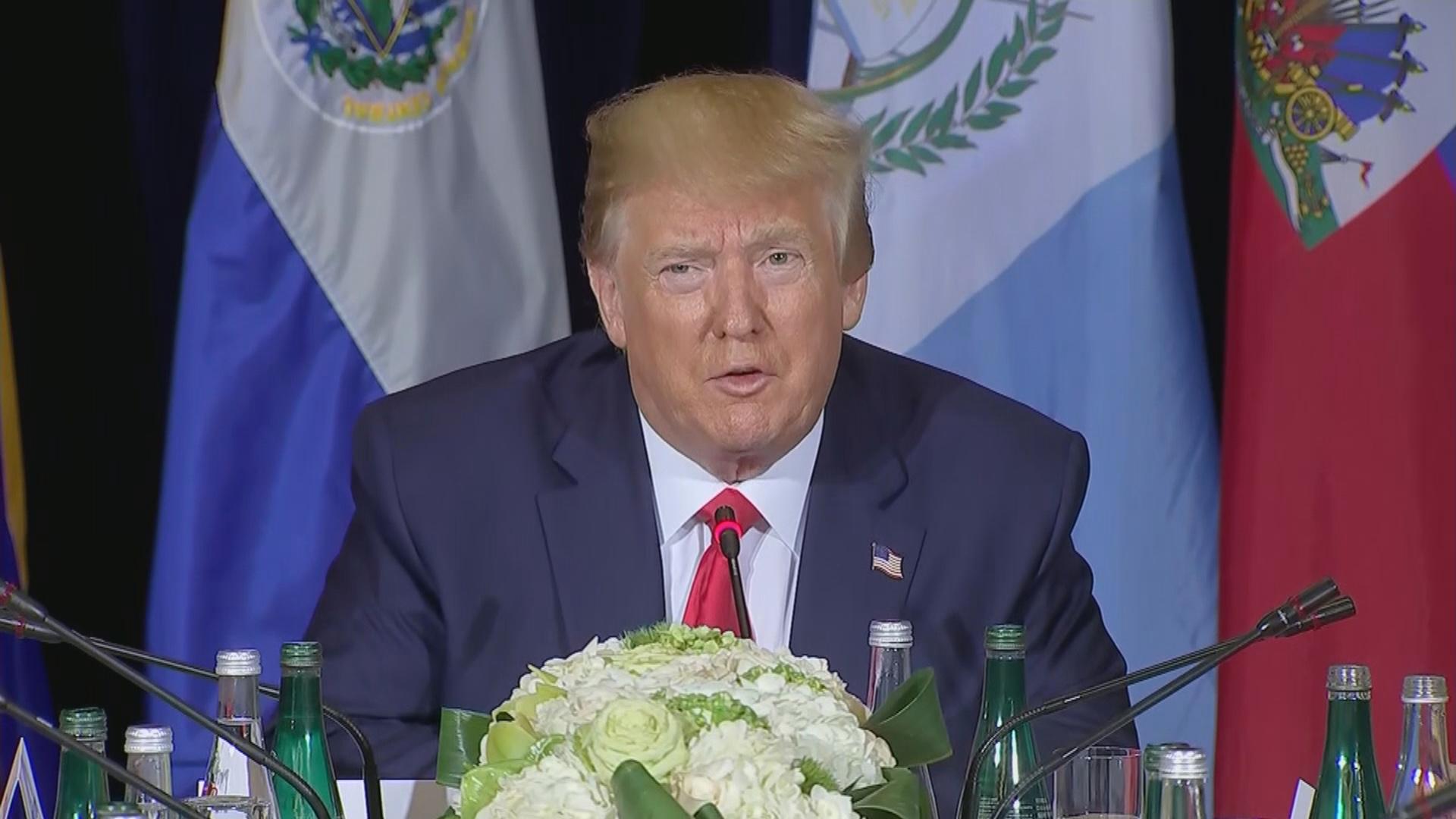

Support for the impeachment of President Donald Trump has grown among Democrats in Congress after the release Wednesday of a reconstructed transcript of the president’s phone call with Ukraine’s president. The document – which is not a verbatim account – reveals that Trump asked Ukraine’s leader to look into Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden and his son Hunter.

Now that an official inquiry has been launched, how exactly does impeachment work, and what are the next steps?

What the Constitution says

A lot is unknown about the process because the Constitution leaves much of it to the imagination. We know that Article II, Section 4 says:

“The President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

We also know that three U.S. presidents have faced some form of impeachment proceedings: Andrew Johnson was impeached and not removed; Richard Nixon resigned before articles of impeachment were voted on; and Bill Clinton in 1998 was impeached in the House but acquitted in the Senate.

The next steps

Committees that are investigating under the auspices of impeachment can bring articles of impeachment before the House. A simple majority is needed to approve the impeachment resolution. It then goes to the Senate for a trial, where the rules are very vague, other than that the chief justice of the Supreme Court presides over it.

“There’s not a lot of precedent for this,” said IIT-Kent College of Law professor Carolyn Shapiro who is director of the school’s Institute on the Supreme Court. “The Senate can make its own rules for how it operates the trial. There are questions as to how it operates the trial at all. Either the majority leader could decide not to bring it to the floor, or it could be dismissed on a motion to dismiss. Those are open questions.”

It would then take a two-thirds majority in the Senate to convict the president and remove him from office, in which case the vice president assumes power.

Investigations underway

House committees have already been investigating many aspects of Trump: his personal finances, whether he has violated the emoluments clause by personally enriching himself, and aspects of the investigation into Russian election interference conducted by Robert Mueller. In many of these instances, the administration has challenged some subpoenas in court and has simply refused to acknowledge others.

Shapiro says that by folding all of this under the umbrella of impeachment, it may give Congress a better chance to have judges enforce all subpoenas.

“What the court would look at is, where is Congress getting its authority to issue it’s subpoena. In this case, Congress would say we have the sole power of impeachment, which must mean we have the power to investigate, because we can’t decide to hold impeachment without investigation. Then, the court would look to see some relationship between the subpoena and the power being asserted,” Shapiro said.

But Democrats may get little more than more court-enforced oversight authority out of impeachment. Republicans hold the majority in the Senate and most came to the president’s defense Wednesday, making the impeachment inquiry more of a political exercise – barring any additional revelations that shift more Republicans into the impeachment camp. Both Democrats and the president want to use this to their political advantage, perhaps raising campaign money and stoking their base for 2020.

“The political stakes involve what happens in 2020, and what is the dominant narrative that comes out of these impeachment hearings?” said professor William Howell, an American political science expert at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy. “Is the dominant narrative about Democrats harassing a dually elected president and making it impossible for him to do his job, or is the dominant narrative about a president who is unhinged, using the powers of his office for his own narrow electoral gains.”

Political fallout?

History doesn’t offer much of a road map to how either party might fare politically at the polls. Former President Clinton enjoyed a high approval rating going into his impeachment and it remained unchanged. But Howell says that doesn’t mean his party did well.

“Democrats suffered mightily during the course of Clinton’s time in office,” Howell said. “They lost both chambers of Congress in 1994, they lost additional seats moving forward, and they lost the White House in 2000 even though the economy was humming, when his VP Al Gore couldn’t win office.”

Follow Paris Schutz on Twitter: @paschutz

Related stories:

Democrats, Republicans React to Launch of Impeachment Inquiry

Memo: Trump Prodded Ukraine Leader on Biden Claims

Pelosi Orders Impeachment Probe: ‘No One Is Above The Law’