From houses of worship to working class homes and apartment buildings to park field houses, brick built Chicago. And brick enthusiast Will Quam believes Chicago is one of the nation’s best showcases for all that a brick can do.

“I like to say bricks are like brushstrokes or like pixels: the more bricks you have and the more varied colors, it’s like having a huge painting full of all these diverse little brushstrokes, like a Van Gogh.”

Chicago’s status as a railroad hub meant that, once brick manufacturing became increasingly industrialized across the country, all sorts of bricks passed through Chicago, allowing it to become a center for brick architecture. “To me the real golden age of brick is from about 1905 to 1930, and that’s when you start seeing Chicago pulling in a lot of brick from all around the country, so you get these buildings built in the 1920s that just have incredible brick work, incredible brick design and brick colors all over them.”

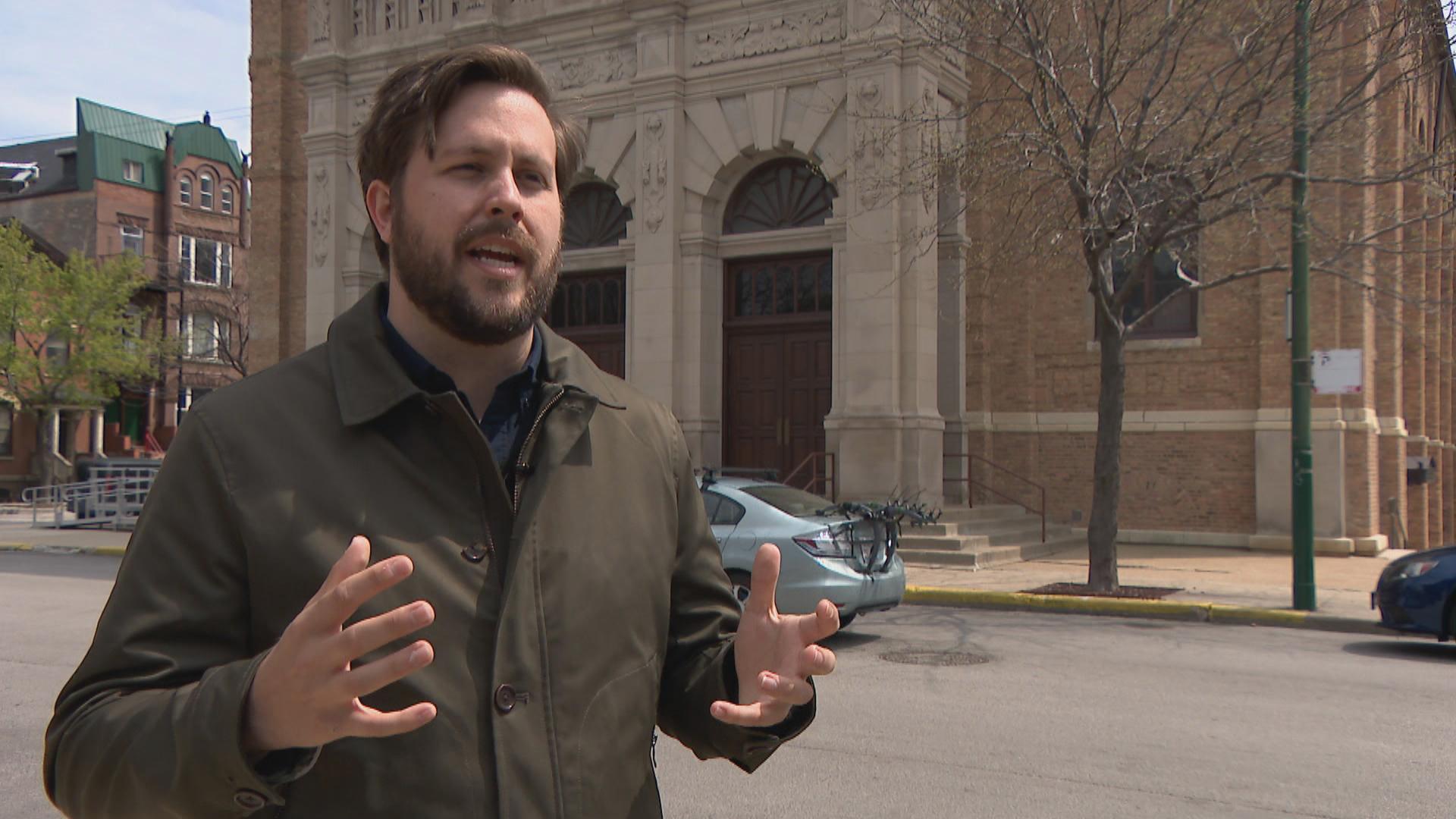

A theater teacher and St. Paul native, Quam says walking the streets of his adopted city made him fall in love with brick’s streetscape symphonies. He began posting photos on an Instagram account called Brick of Chicago, and began studying everything he could find on brick history and manufacturing. Today, Brick of Chicago has about 5,000 followers, and he also organizes walking tours of neighborhoods to spread the brick gospel.

Like the brick itself, Chicago’s love affair with brick was born from fire. Quam says, “When Chicago burned down in 1871, it was built mostly of wood, and after that they really needed to rebuild in a way that they couldn’t burn down again.”

The answer, of course, was brick, and brick factories appeared all around the city to meet the new demand, using local clay to churn out what became known as “Chicago common bricks” by the millions. At the peak of common brick production in the 1920s, Chicago was home to over 60 different manufacturers.

Most often seen in alleys, the Chicago common brick has become prized by architects and designers for its character, creating a whole new industry for the old material. At Bricks Inc in Little Village, Chicago commons are reclaimed from demolished buildings, then cleaned and shipped off for use in projects across the country.

Roberto Garcia started with Bricks Inc when he was just a teenager as a brick cleaner. Today, Garcia manages the company’s brick reclamation projects. “Back in those days they used to pay us $7 a pallet and you would stack three, four or five – it all depends on how the job went. It’s not easy work; a lot of people don’t like it.”

In the Pulaski Park neighborhood, the 1881 St. Stanislaus Kostka Church imposes itself into the skyline. Quam says St. Stan’s is an outstanding example of how thoughtful technique can elevate the humble Chicago common brick to the divine. “1881, this was an era when they were making all their bricks with their hands or very simple machines, so each brick is so different and so varied in its character. What I love about it is, it’s not built with a lot of ostentatious ornamentation – it’s all done through the brick. The masons were so careful in pushing some rows back and pushing some forward and they create these super intricate patterns,” he says.

During Chicago’s boom years, municipal edifices used exuberant colors and patterns, called bonds, to exalt purpose-built structures like Cleveland Elementary, designed by Chicago Public Schools chief architect Dwight Perkins in 1909. “Dwight Perkins used brick on this building as if he was weaving a tapestry and used contrasting layers of brick to make it look like woven fabric.”

Even residential buildings used different bonds, textures and colors of brick to create interest, to liven up a single block.

Brick enthusiast Will Quam

Brick enthusiast Will Quam

While Chicago takes a great deal of public pride in its architecture, in Quam’s opinion, the city doesn’t do a great job of maintaining its neighborhood brick treasures. “I think that comes down to the people who own the buildings. They’re not interested in spending the money to make the facade look good. This building was built with these colors and design elements, and that costs extra to do, but it made the building more enticing, it made the building more inviting, it made this courtyard a lovely place to be. Brickmaking and brick designing is becoming more and more of a lost art.”

But Quam believes once people start seeing the everyday artistry of Chicago’s brick buildings, they’ll value them more, and that’s why he’s creating a community of brick lovers the only way he knows how – one brick at a time.

Related stories:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House Reopens After Massive Renovation

‘Missing’ Uptown Chandeliers to Make Their Way Back Home

Conversion of Logan Square Church into Apartments Sparks Gentrification Debate