A viewer says her uncle used to swipe eggs from a factory in Bronzeville in the 1940s or ‘50s. Local history eggs-pert Geoffrey Baer has the surprising answer to that question, and floats some theories about one of Chicago’s most enduring mysteries.

Do you know of any egg factory in Chicago’s Bronzeville area during the 1940s or ‘50s? My dearly departed Uncle Lemonte told us stories how he would, as a young boy, misbehave and steal eggs from a nearby egg factory.

– Kim Adkins, West Loop

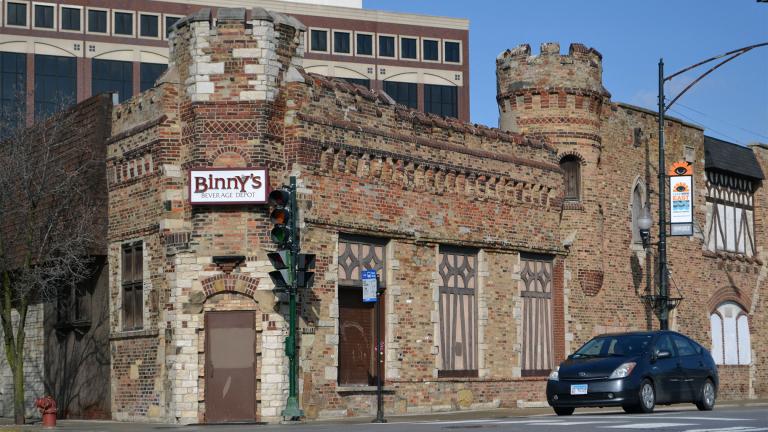

We think our viewer’s Uncle Lemonte’s childhood egg capers happened at the Murphy Butter and Egg Company, at 20th Street and Calumet, a little north of Bronzeville.

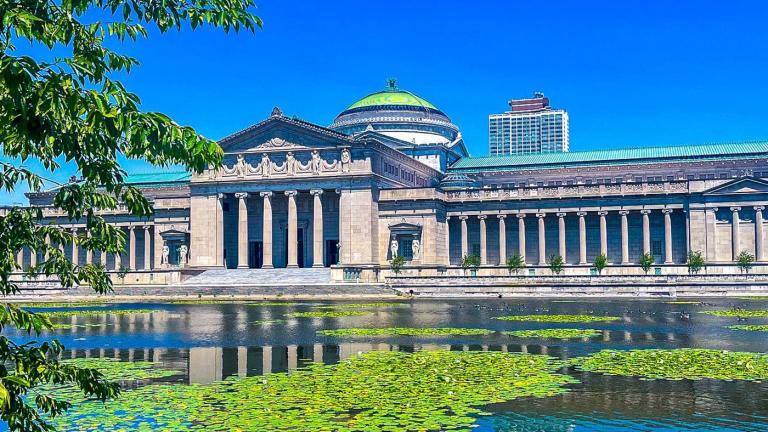

The building is still standing today, but it most definitely does not look like a butter and egg warehouse – and that’s because it originally was built as a private home for a wealthy Chicago family. Today, it’s been beautifully restored and is a boutique bed and breakfast.

But how it became storage for poultry and dairy products is really the story of the rise, fall and rebirth of the neighborhood. Calvin Wheeler, a banker and onetime Chicago Board of Trade president, built the home at 2020 S. Calumet in 1870. Somewhat confusingly, the designer of Wheeler’s house was a man named Otis Wheelock, who was a prominent architect in pre-fire Chicago.

At the time, the neighborhood now known as the Prairie Avenue District was fast becoming fashionable for Chicago’s early mercantile and industrial barons like George Pullman, Marshall Field, and later, the Glessners. The neighborhood is often referred to as Chicago’s first Gold Coast and back then was sometimes called “the sunny street that held the sifted few.”

Wheeler and his family lived in their mansion until 1874, when they sold it to clothing wholesaler Joseph Kohn. The Kohns lived in the home for the next 34 years.

But as industry and vice districts moved into the neighborhood, its moneyed residents moved out, including the Kohns. The house was sold to a publishing company, which published books and religious tracts there. In 1944, the property was sold to the Murphy Butter and Egg Company, which already had its offices in the neighboring house. In the photo below, you can just make out an ad on the house that says “good milk” – the Wheeler house is to the left of that house.

(Courtesy of the Glessner House Museum)

(Courtesy of the Glessner House Museum)

After Murphy Butter left the property in the 1980s, the home sat vacant for years and was repeatedly threatened with demolition, but in 1997 the Wheeler House was rescued when it was purchased for just $10,000. After two years of restoration, the home was granted Chicago and national landmark status and in 2004, won a Richard H. Driehaus Foundation Preservation Award for its restoration.

What happened to the Foolkiller submarine, pulled from the Chicago River in 1915?

– Sylvester Knight, Fernwood

(Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

(Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

The short answer: no one knows. This is not only a mystery, it’s one of the most bizarre Chicago stories we’ve ever come across. Here’s what we do know.

It starts with a diver named William “Frenchy” Deneau, who became a local celebrity following the Eastland disaster of July 1915 that killed 800 people. Deneau claimed to have recovered 250 bodies from the river, but Deneau is frequently described as a showman who didn’t let facts get in the way of a good story, so we can take that claim with a grain of salt.

A few months later, Deneau was laying cable at the bottom of the river when he struck something solid in the muck. It was a homemade submarine about 40 feet long. Where exactly in the river Deneau found it has been variously reported as below the Rush Street bridge, the Wells Street bridge, and the Madison Street bridge – questionable newspaper reporting is a recurring theme in this story.

William “Frenchy” Deneau (Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

William “Frenchy” Deneau (Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

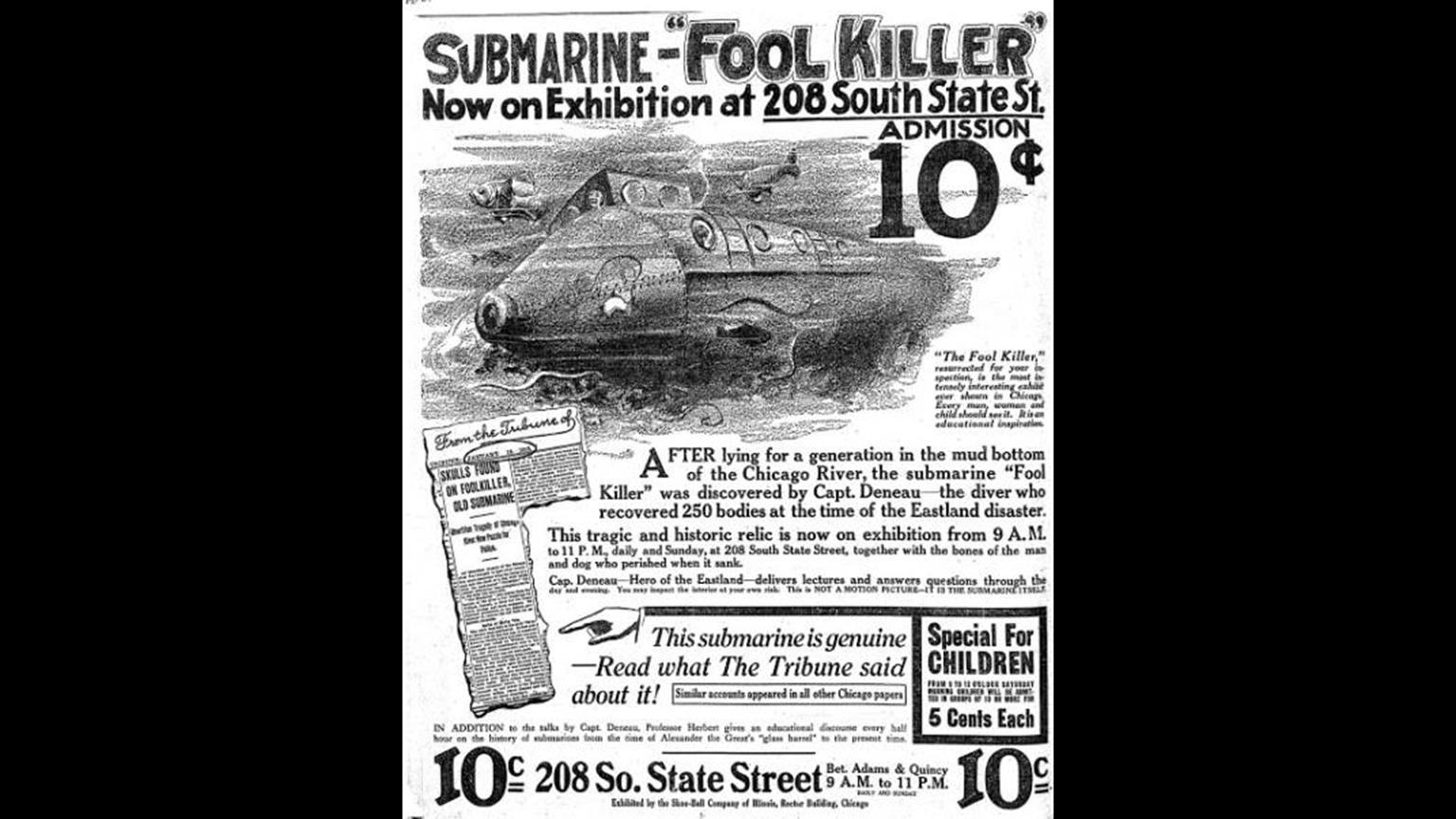

Wherever it was, Deneau got special permission from the federal government to raise it himself in January 1916, and once it was up, Deneau discovered human bones and a dog’s skull inside. Of course, today a gruesome discovery like this would automatically lead to an investigation by authorities, but the showman Deneau saw it as a business opportunity. He displayed it on State Street, and charged a dime for looky-loos to gawp at the submarine and its skeletons.

The first theory newspapers floated was that the vessel belonged to a Chicago accountant-slash-inventor named Peter Nissen, who dabbled in experimental vessels like this. That’s where the name “Foolkiller” came from, since that’s what Nissen named his inventions. However, since Nissen had died in another craft in 1904, the skeleton inside could not have been his.

It tells you something about the 19th century that Nissen wasn’t the only guy who could’ve built a homemade submarine back then. In the 1840s, a Michigan City shoemaker named Lodner Philips built primitive subs that reportedly worked quite well, and one of his designs looked a lot like the submarine Deneau recovered. But the skeleton found in the submarine could not have belonged to Philips, either, because he died in New York. To this day, no one knows where the skeletons came from.

The submarine itself is just as mysterious as the skeletons. It appears that Deneau sold it to a carnival, Parker’s Greatest Shows, who took it on tour in Iowa in the summer of 1916. Until recently, that was the last known location of the submarine, but a few years ago a University of Illinois at Chicago grad student Jeff Nichols found an ad from September 1916 that seems to indicate the submarine came back to Chicago from Iowa and was on display at Riverview Park. So for now at least, that’s where the mystery sub drops off the record – but as more and more periodicals get digitized, who knows what might turn up next?

Special thanks on this story go to historian Adam Selzer, who helped us get our story straight on the Foolkiller and whose extensive reporting on the sub-ject (get it?) is at his website, Mysterious Chicago.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.