The city of Waukesha on Tuesday was given a green light to divert water from Lake Michigan for its drinking water supply after eight representatives from the states that border the Great Lakes voted unanimously to allow the diversion. A single no vote would have scuttled the city's plan.

Waukesha is the first city to apply for a diversion of Great Lakes water since a ban on such practices was enacted in 2008. The city, located about 17 miles west of Lake Michigan, is faced with a drinking water crisis, as wells supplying its water have been found for several years to contain levels of the radioactive element radium that exceed regulatory limits set by the Safe Drinking Water Act.

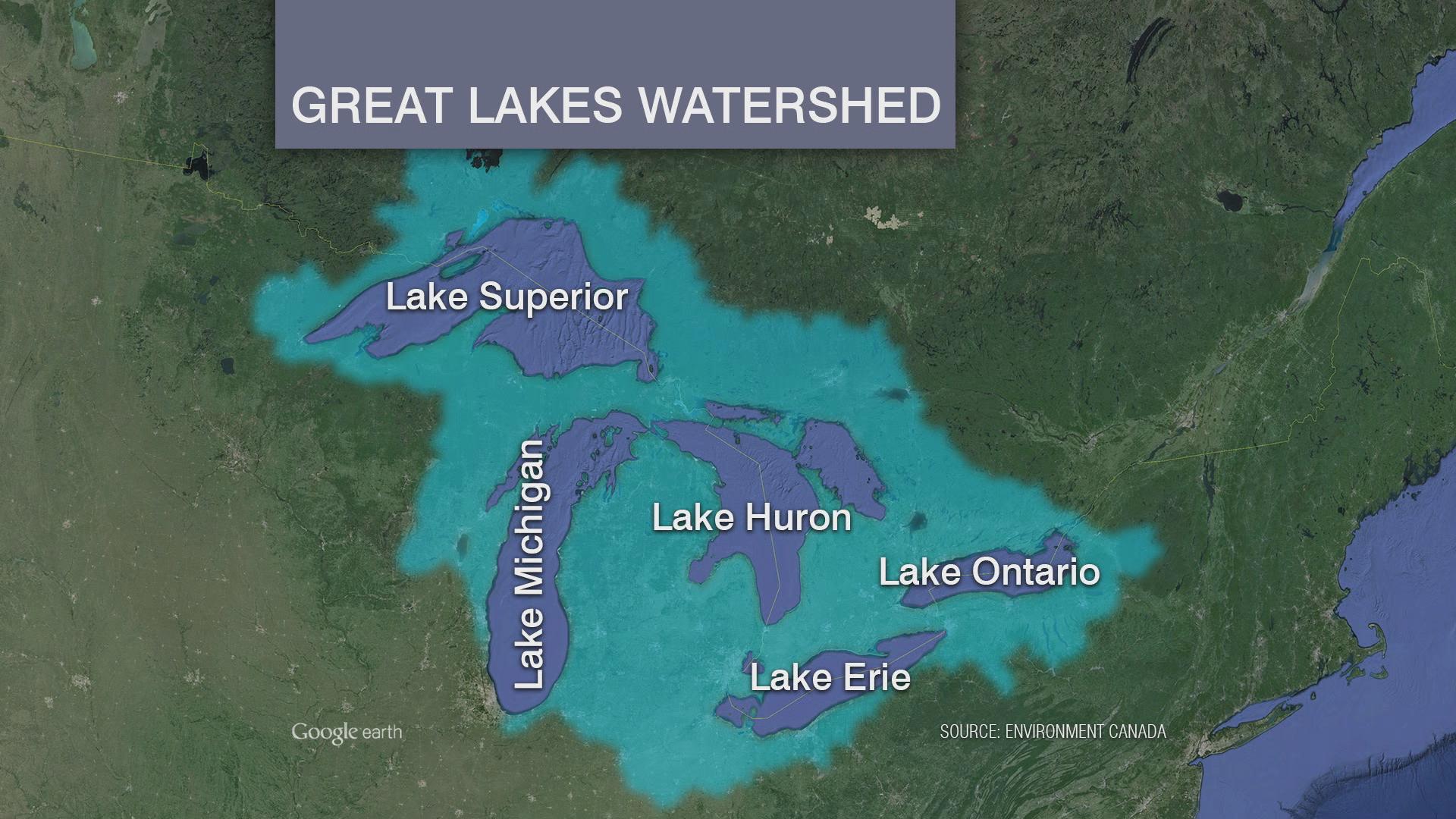

The Great Lakes Compact prohibits diverting water from Lake Michigan and the other the Great Lakes outside of the Great Lakes watershed, where bodies of water form a drainage basin that feeds into the lakes. The law was approved by all eight governors of states within the watershed: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

There are, however, exceptions to the ban: A community outside the watershed, like Waukesha, can apply for access to Great Lakes water if they’ve exhausted all other options.

Related: Faced with Water Crisis, Waukesha Looks to Lake Michigan for Help

Related: Faced with Water Crisis, Waukesha Looks to Lake Michigan for Help

Opponents of the water diversion proposal had worried that approval could set a bad precedent, opening the doors for communities near and far in drought-stricken or contaminated-water areas to start draining freshwater from Lake Michigan. Critics also cautioned that water treated at a municipal water treatment plant may contain harmful contaminants that could make their way back into Lake Michigan.

"We're going to watch really closely what sort of impacts might occur on the Root River with regard to return flow," said Molly Flanagan, vice president of policy for the environmental organization Alliance for the Great Lakes. "There are some very legitimate local concerns about that river that we need to make sure are taken care of."

Following Tuesday's decision, Flanagan said there was a possibility of legal action from environmental groups like hers, but that a review period of the application process was under way.

"I think a number of organizations are going to need to review the compact council's decision and look really carefully at what the compact council did," Flanagan said. "I don't want to speak for everyone in the environmental community, but I think people will weigh their options and probably make a decision pretty soon one way or the other."

But a representative for Gov. Bruce Rauner said Tuesday an affirmative vote was an easy decision based on the severity of Waukesha's problem.

"We looked at their current source of water," said Dan Injerd, the director of water resources for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. "We are well aware of the problems that radioactivity presents in wells. This is not a health issue that you should take lightly."

The EPA had given the community of about 70,000 people until 2018 to find a suitable and safe solution to their drinking water problem, but city officials said it would not be able to meet that deadline.

The city also said its groundwater isn’t flowing as freely as it used to. After deciding that drilling deeper wells for more water would only cause greater spikes in radium levels, Waukesha formally applied to divert Lake Michigan’s water in January 2016.

Injerd said the arduous process Waukesha faced in obtaining permission to divert water from Lake Michigan will actually make it harder, not easier for any future communities outside the Great Lakes watershed to do the same.

"Waukesha has been studying and analyzing this problem for over 10 years and have spent millions of dollars getting to this point," Injerd said. "We've set an extraordinarily difficult set of criteria, study and analysis that anybody would have to pursue if they wanted to get serious about bringing forth an application. To me, there is no slippery slope. The slope, if anything, instead of pointing downward, is pointing steeply upward."

Under the new agreement, Waukesha must submit annual reports to the compact council documenting the daily, monthly and annual amounts of water diverted from Lake Michigan the prior calendar year.

Waukesha's plan includes building a pipeline that takes Lake Michigan water from Oak Creek, Wisconsin, a city in neighboring Milwaukee County that's within the Lake Michigan watershed. Per the rules of the compact, Waukesha would have to return the same amount of water it takes from Lake Michigan back into the lake. The water would be treated at a Waukesha water plant and dumped into the Root River, where it would flow into Lake Michigan by way of Racine, Wisconsin.

Waukesha says its pipeline plan, which would cost $207 million, would likely not be finished until 2020.

Follow Evan Garcia on Twitter: @EvanRGarcia

Sign up for our morning newsletter to get all of our stories delivered to your mailbox each weekday.

Related "Chicago Tonight" Stories

Study: Carbon Dioxide Could Keep Asian Carp out of Great Lakes

Study: Carbon Dioxide Could Keep Asian Carp out of Great Lakes

June 15: A process similar to making soda water may be an effective strategy in warding off an Asian carp invasion that’s threatening the health of the Great Lakes, including Lake Michigan.

Faced with Water Crisis, Waukesha Looks to Lake Michigan for Help

Faced with Water Crisis, Waukesha Looks to Lake Michigan for Help

May 24: The city of Waukesha, Wisconsin wants to take just over eight million gallons of water a day from Lake Michigan for the city's drinking water. But environmental activists warn that allowing access could set a dangerous precedent.

As Risk of Great Lakes Oil Spill Grows, So Do Concerns About Cleanup

As Risk of Great Lakes Oil Spill Grows, So Do Concerns About Cleanup

Dec. 15, 2015: The risk of a Great Lakes oil spill has grown as the region becomes a hub for refining and transporting heavy tar sands oil. Oil that the Coast Guard says it doesn't have a method to clean up.