The centerpiece of mayoral candidate Paul Vallas’ plan to reverse decades of disinvestment on the South and West sides of Chicago is the creation of an independent community development authority that would limit the ability of Chicago City Council members to have final say on ward-level issues.

That proposal takes a page from Mayor Lori Lightfoot, whose 2019 campaign centered on promises to end aldermanic prerogative as part of efforts to root out the corruption that led to the criminal conviction of 37 members of the Chicago City Council since 1969.

But even before a pandemic, economic collapse and crime surge swamped Lightfoot’s single term in office, she met with ferocious opposition at every turn from members of the City Council, including the majority of the returning alderpeople who have endorsed Vallas. Lightfoot will leave office with aldermanic prerogative, sometimes known as aldermanic privilege, weakened but intact.

Several members of the City Council told WTTW News they thought there was little appetite to reconsider the decades-old practice giving aldermen a veto over ward issues, especially since Lightfoot’s promise soured her relationships with many alderpeople before she spent a single day in office.

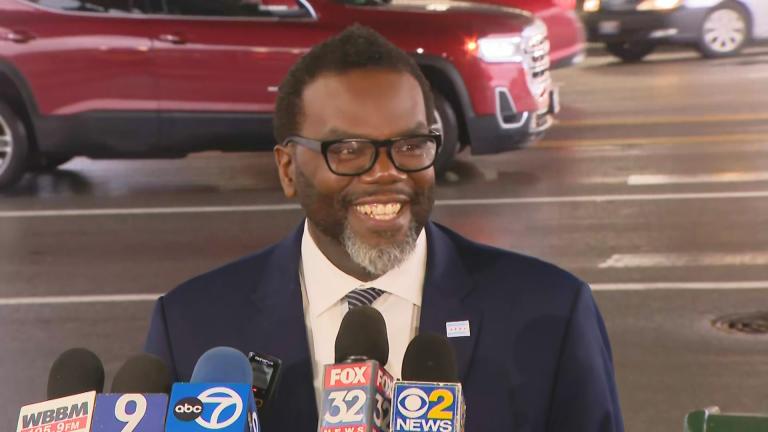

During the first debate of Chicago’s mayoral runoff election, both Vallas, the former CEO of the Chicago Public Schools, and Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson vowed to continue the Invest South/West initiative started by Lightfoot, who finished in third place in the Feb. 28 election. Vallas won approximately 33% of the vote, with Johnson garnering nearly 22%, according to unofficial returns.

The independent community development authority would “operate freed from City Hall politics – the fifth floor and aldermanic privilege,” according to Vallas’ economic development plan, which runs nearly 1,500 words. “The determinations of what must be done will not be driven by LaSalle Street and the Department of Planning and Development (DPD), rather it will be grounded in a community-based process drawn from community leadership.”

The office of Chicago’s mayor sits on the fifth floor of City Hall, and much of Chicago’s financial services industry is located in the LaSalle Street corridor in the Loop. The mayor appoints the head of the Department of Planning and Development, who must be confirmed by the City Council.

Since October, employees of Citadel, a hedge fund located on Dearborn Street in Chicago’s financial services district, have given Vallas’ campaign committee more than $700,000, including $200,000 from Chief Operating Officer Gerald Beeson. Employees of Madison Dearborn, a private equity firm located near its namesake corner, gave Vallas more than $1.25 million, including $200,000 from Managing Director James Perrt, Jr., according to records filed with the Illinois State Board of Elections.

Vallas’ campaign did not respond to email messages from WTTW News requesting more information about how the community development authority would interact with the City Council, how much it would cost to operate and exactly what authority it would have.

Vallas, who served as budget director under former Mayor Richard M. Daley from 1990 to 1993, said the community development authority was prompted by the fact that that city institutions had “negligently fostered the reinforcement of inequities” in neighborhoods across Chicago, but especially in “communities of color, where the government has generally failed to provide a safe public environment, nor supported the development of local economies prioritized, owned, sustained by those within the community itself.”

The community development authority envisioned by Vallas would leverage the city’s financial resources to “renovate homes, finance small businesses, provide microfinance loans, develop industrial parks, finance locally owned and operated social services,” according to Vallas’ website.

The community development authority would be “grounded in a community-based process drawn from community leadership, rooted in asset-based community development process and objectives.”

Projects approved by the authority would prioritize working with small businesses owned by Chicagoans and staffed by those returning to Chicago from jail or prison, according to Vallas’ website.

Vallas also proposes creating a municipal bank, which would hold the authority's funds, which would come from “a dedicated portion of all new revenues from [tax-increment financing districts] and all developer fees, future casino, sports betting and gaming revenues” that would be earmarked for investments on the South and West sides.

“These are the very neighborhoods that have received little financial help and been on the receiving end of predatory lending practices going back decades,” according to Vallas’ website.

However, state law requires Chicago to use all casino revenues to fund its police and fire pensions. Even though video gaming was approved by the state in 2009, the City Council has not legalized video gaming in the city.

Vallas would also create a city land bank to acquire “control of other non-performing real assets like closed industrial sites, shuttered business corridors and vacant property and support their development into locally owned performing assets,” according to his website.

That land bank would be empowered to borrow against the property tax revenue that flows into the city’s tax-increment financing districts and use “eminent domain to secure all vacant residential buildings and vacant lots to be turned over to local developers and community organizations for development,” according to Vallas’ website.

Vallas said he would also require any “major community economic development” to sign an agreement with the city “that takes into account cumulative environmental impact and commits funds to social service infrastructure as part of the development itself,” according to Vallas’ website.

That provision would likely draw significant resistance from the leaders of large development firms, who have routinely resisted efforts by progressive groups to ink community benefit agreements in return for special permission from city officials or a city subsidy.

Aldermanic Prerogative’s Deep Roots

Aldermen exercise their prerogative at every committee meeting and at every council meeting on items ranging from sign permits to liquor licenses. But most of aldermen’s historic clout comes from the fact that they alone have had the power to approve — or veto — proposals of all sizes.

That unwritten code also calls on other aldermen to mind their own business, and vote along with the alderman whose ward includes the project.

Only Ald. Anthony Napolitano (41st Ward), who has endorsed Vallas, endorsed the plan as a way to breathe new life into areas of the city that have suffered from disinvestment for decades.

“I think it is a terrific idea,” Napolitano said. “I think what Paul (Vallas) wants to do is bring us all together.”

However, Napolitano said any decision made by the new authority would have to come before the City Council for approval. Without the support of that ward’s alderperson, those projects would be hard pressed to advance under the unwritten practice of aldermanic prerogative.

Ald. Brendan Reilly (42nd Ward) and Ald. Walter Burnett (27th Ward) told WTTW News they were unfamiliar with this part of Vallas’ campaign platform and had not evaluated the proposal to create an independent community development authority. Both Reilly and Burnett, who have endorsed Vallas, fiercely defended aldermanic prerogative under Lightfoot.

Ald. Brian Hopkins (2nd Ward), who has also endorsed Vallas, did not respond to messages from WTTW News. Ald. Matt O’Shea (19th Ward) and Ald. Raymond Lopez (15th Ward) endorsed Vallas on Sunday.

That lack of robust support among even Vallas’ core supporters means the proposal faces an uphill battle to become law.

Challenge by Federal Authorities

The biggest threat to the continued persistence of aldermanic prerogative in Chicago could stem from an ongoing federal probe that has lasted more than two years.

Prompted by a civil rights complaint filed in November 2018 against the city by the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, a coalition of groups that have urged city officials to take steps to desegregate the city and provide more affordable housing.

That complaint contends aldermanic prerogative has created a hyper-segregated city rife with racism and gentrification. A ruling by the federal agency could come at any time.

Only once during Lightfoot’s tenure did the City Council vote to defy aldermanic prerogative. That vote came over the objections of Napolitano to allow an apartment complex with 297 units — including 59 set aside for low- and moderate-income Chicagoans — to be built in the 41st Ward near O’Hare Airport.

Aldermanic prerogative also shaped the future of the planned Chicago casino. Burnett was the only alderperson whose ward included one of the finalists to welcome the controversial development. That played no small role in Lightfoot’s decision to select Bally’s plan to build the casino in River West.

However, supporters of aldermanic prerogative tout it as the best way to ensure that Chicago residents live in neighborhoods governed by one of their own: someone who lives near them, understands their issues and is not only accessible — but also accountable to them on Election Day.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]