Gayeon Jung and Victoria Jaiani of the Joffrey Ballet perform in George Balancbine’s “Serenade.” (Credit: Cheryl Mann)

Gayeon Jung and Victoria Jaiani of the Joffrey Ballet perform in George Balancbine’s “Serenade.” (Credit: Cheryl Mann)

For its spring season at the Lyric Opera House, the Joffrey Ballet has devised a program composed of two dramatically and stylistically different works.

Opening the program is George Balanchine’s 1934 “Serenade,” the first ballet that the Russian-bred choreographer created upon arriving in America. The work was devised for the students in the school he established — a school that would set the groundwork for his New York City Ballet company. It is a dreamy encyclopedia of classical ballet technique that is also marked by a subtle modernity that frees it from traditional ballet scenarios.

Ironically enough, the Joffrey program’s second half — the world premiere of British choreographer Cathy Marston’s “Of Mice and Men,” based on the classic John Steinbeck novella published in 1937 — is pure theater. Marston has a well-established gift for creating intensely dramatic, character-driven works, and has drawn on a wide range of literary sources from “Jane Eyre” (an exceptional piece ideally performed by the Joffrey in 2019), to “Wuthering Heights” and “Lolita.”

Each of the program’s two works can easily stand on its own, but seen back-to-back they serve as a vivid example of how the very definition of ballet has expanded and changed over the course of almost a century.

But before going any further, a note of appreciation for the impeccable Lyric Opera Orchestra and conductor Scott Speck who prefaced the program with a performance of “Melody,” a beautiful piece by the Ukrainian composer Myroslav Skoryk (who died in 2020) that briefly brought the tragedy of all wars to mind.

And now to “Serenade,” a breathtakingly lovely example of Balanchine’s oft-quoted proclamation that “ballet is woman.” Immensely demanding in terms of the meticulous synchrony, balance and sculptural arm movements required from its 20 female dancers, it is at the same time remarkably free-flowing in its overall mood. And though precision-tuned in every formation, it also gives the sensation of moving like the wind.

Set to the music of Tchaikovsky, that master of ballet scores, the work’s dancers are set against a deep blue background and costumed in the original long, diaphanous, pale blue dresses created by Balanchine’s designer of choice, Barbara Karinska. And they are a beautiful enhancement to every sweeping movement and floor pattern in this work. It is a ballet that demands remarkable control while at the same time seeming effortless.

The solo turns by the ever dazzling Victoria Jaiani, in addition to Valeria Chaykina and Gayeon Jung, were impeccable, and added a jolt of drama. And there was fine partnering by Edson Barbosa and Stefan Goncalvez. But this is, above all, an exquisite ensemble work in which all 26 dancers must breathe as one.

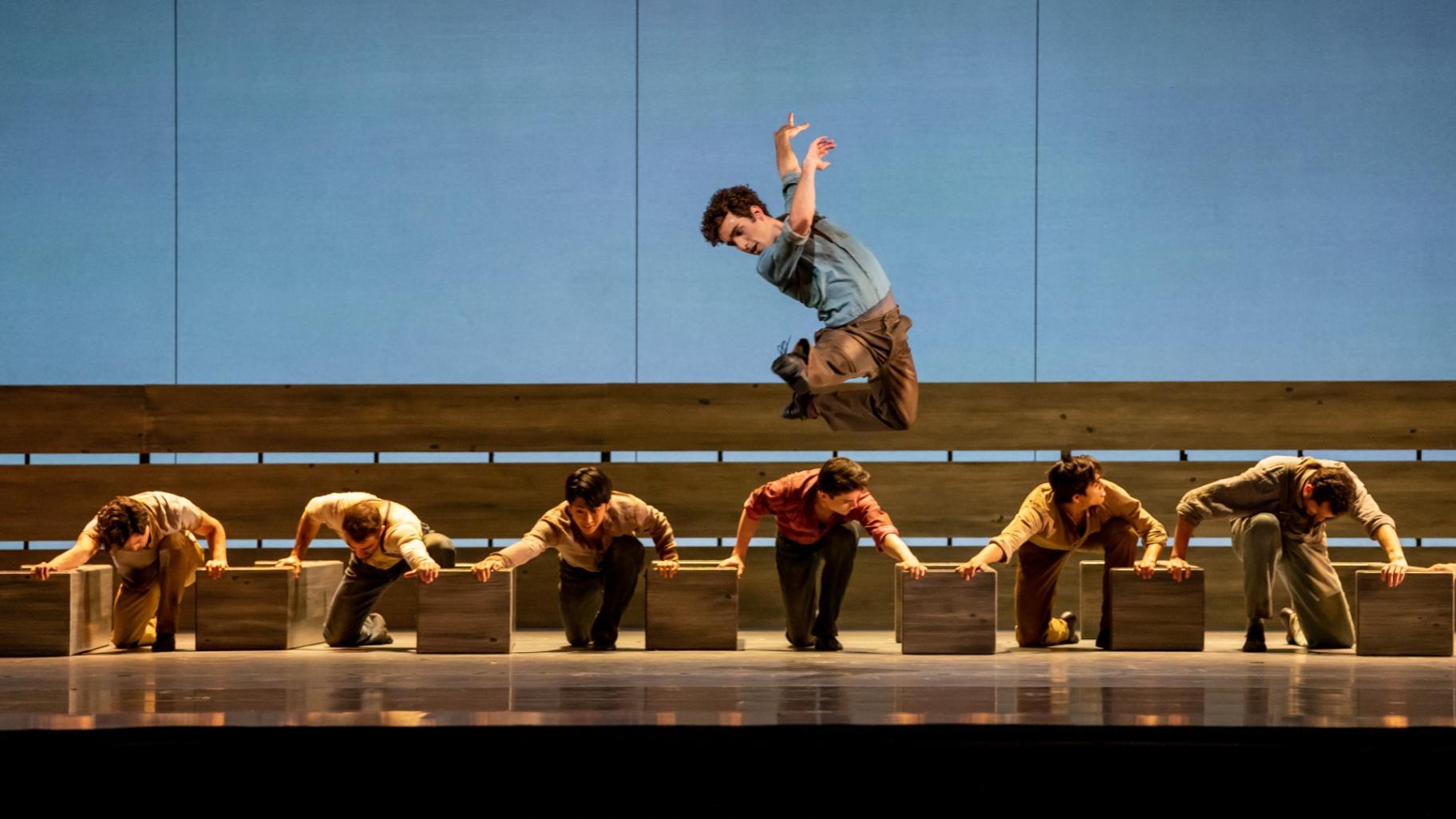

Edson Barbosa and the Joffrey Ballet ensemble perform in Cathy Marston’s “Of Mice and Men. (Credit: Cheryl Mann)

Edson Barbosa and the Joffrey Ballet ensemble perform in Cathy Marston’s “Of Mice and Men. (Credit: Cheryl Mann)

And now, onto “Of Mice and Men,” which is based on Steinbeck’s story of migrant farmworkers during the Great Depression — men desperate to own their own little piece of land. At the core of the story is the unlikely but deep friendship between two very different men: George, a bright, serious-minded young man (performed here by two dancers — Xavier Nunez and Alberto Velazquez — a choice I do not understand), and Lennie (in a most winning turn by Dylan Gutierrez), a big, physically strong, but mentally disabled fellow whose need to fondle soft things ranges from rabbits to a seductive, free-spirited and married woman.

That woman, who has no name (and is superbly danced and acted by Amanda Assucena) is badly treated by her angry, jealous and controlling husband, Curley (deft work by Fernando Duarte), the son of the Boss (Miguel Angel Bianco) of the ranch where George and Lennie, along with others, have found work.

Things go bad after Lennie gets into a fight with Curley and seriously injures his hand. And then they go from bad to worse when Curley’s unhappy wife, who playfully flirts with Lennie, even invites him to pet her hair just as he pets his rabbits. When she suddenly becomes scared, Lennie tries to quiet her but accidentally kills her. And George instantly realizes that if he is to save Lennie from being lynched, he must quickly kill his friend himself.

Not everything unfolds clearly in the storytelling here, and Marston might have developed the relationship between George and Lennie more fully, and given the supporting characters more distinctive characterizations.

Those unfamiliar with Steinbeck’s novella might even feel a bit lost at certain points along the way. Much of what holds the ballet together is the evocative, cinematic and splendidly played score by Thomas Newman, among whose many film scores are those from “The Shawshank Redemption,” “Finding Nemo,” and the James Bond movie “Skyfall.”

And there is this: The one greatest takeaway from the program is that the Joffrey dancers are not just sublime dancers but also exceptionally skillful actors who invariably turn movement into a powerful form of speech.

This program runs through May 8 at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N. Wacker. For tickets visit joffrey.org or call (312) 386-8905.

Next up for the Joffrey is Yuri Possokhov's full-length ballet “Don Quixote,” which runs June 2-12 at the Lyric.

Follow Hedy Weiss on Twitter: @HedyWeissCritic