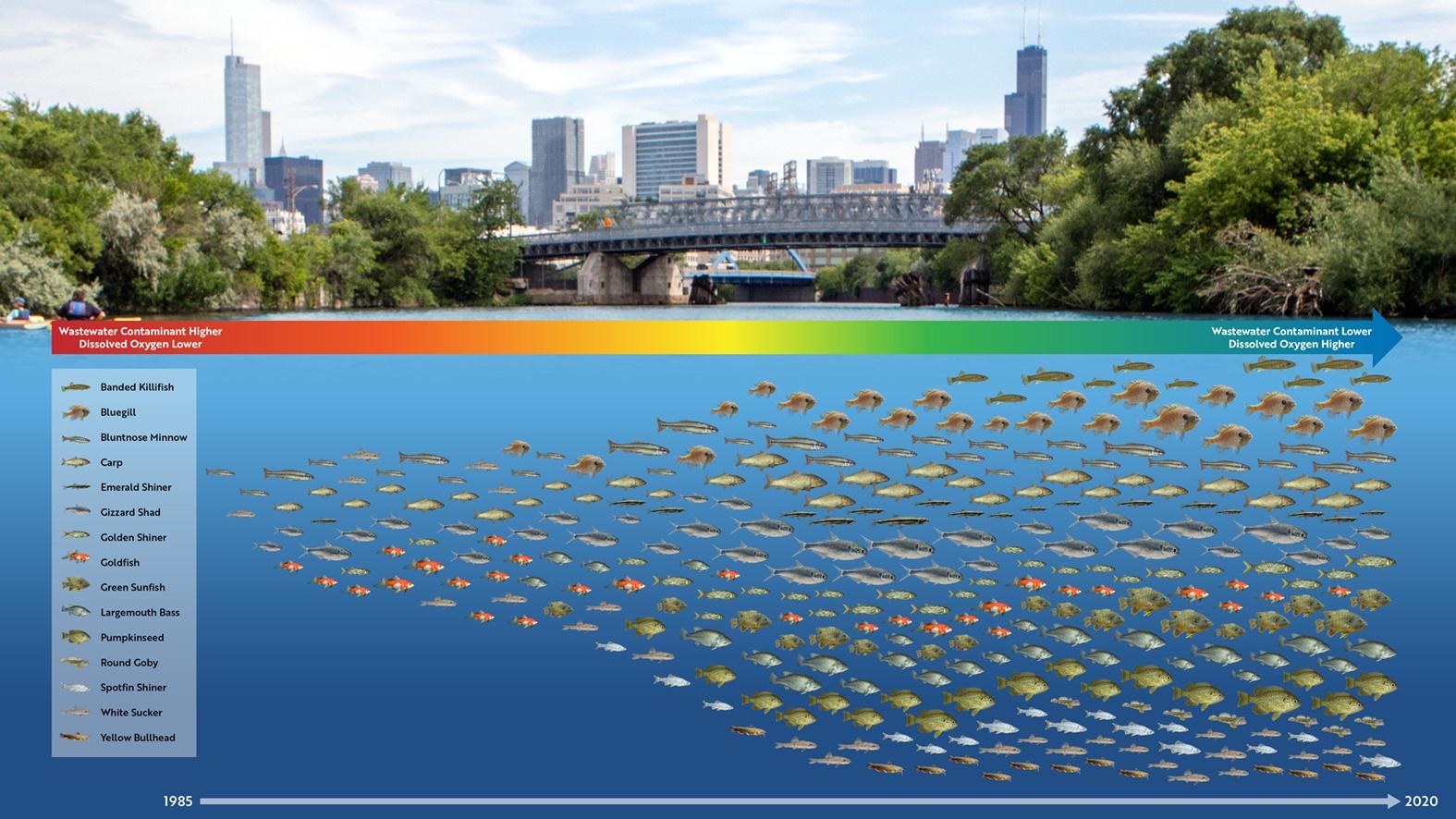

Back in the 1980s, the number of fish species in the Chicago River could be counted on a single hand. Those included goldfish, which can live in a bowl, and bluntnose minnow, a species so plentiful it’s used as bait.

With apologies to Frank Sinatra, if a fish could make it here, it could make it anywhere.

Today, more than 60 species are found in the river, an increase in diversity that can be directly attributed to a decrease in wastewater pollutants, according to a new study from the Shedd Aquarium.

Biologist Austin Happel, a member of the Shedd’s conservation research team, was lead author of the study, published in Science of the Total Environment. Dustin Gallagher, an aquatic biologist at the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, collaborated on the study.

The project built on previous research results that showed fish diversity had increased in linear fashion. The goal of the new study was to isolate why. Fish populations were recovering, meaning something positive was happening in the region’s waterways, but what?

(Shedd Aquarium)

(Shedd Aquarium)

Every year, MWRD samples fish at two dozen locations. Happel took that data, dating back to 1985, and layered on water quality and weather data. He then used machine learning to determine which conditions were most likely to produce an increase in species.

Happel explained the process: Data is input into a statistical model, and then an algorithm runs through the possibilities. “You ask, ‘If the number of fish species went from 5 to 10, what variables get you there?’ It ‘votes’ on what variables are most important.”

When it came to fish in the Chicago-area waterway system, variables related to wastewater treatment, particularly a decrease in the presence of fecal bacteria, were the greatest predictors of species richness.

The results have implications not just for Chicago but for urban waterways across the globe, Happel said.

Investment in wastewater treatment and infrastructure is expensive and the impact isn’t necessarily immediate when it comes to wildlife. “The changes can take years or decades to become apparent,” he said. “You might wonder if it worked or if it was worth the money.”

MWRD’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (aka, Deep Tunnel), commissioned in the 1970s, is one such investment. As massive reservoirs like Majewski, Thornton and McCook have come online, MWRD has been able to capture and store stormwater and sewage that would otherwise have overflowed, untreated, from sewers into waterways during major rainstorms and snowmelts.

Every time one of the reservoirs was brought into service, the spike in the number of fish was noticeable, said Margaret Frisbie, executive director of Friends of the Chicago River. Now, that observation has been quantified.

Frisbie credits MWRD for having shifted its organizational mindset away from a focus on handling sewage to an emphasis on the broader health of the region’s waterways and ecosystems.

“They are thinking about climate change, they are thinking about green infrastructure,” Frisbie said.

Those will be necessary considerations, Happel said, if the region's rivers are to maintain hard-won gains in water health.

“My conclusion was ‘Hey, look, this stuff worked, but our job’s not done,’” he said.

Progress could be reversed if severe rainfall and flooding events become more intense and frequent, due to climate change, Happel said. The Deep Tunnel system won’t have enough capacity, and untreated waste and stormwater will once again wind up in rivers in greater amounts.

Instead of defaulting to “let’s build bigger reservoirs,” the plan should be to capture more stormwater where it falls, Frisbie said. Rain gardens, swales, porous pavement and other forms of green infrastructure should be prioritized over “gray” infrastructure like tunnels. “That’s the next leap forward,” she said.

A heavily salted sidewalk crossing along the North Branch of the Chicago River. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A heavily salted sidewalk crossing along the North Branch of the Chicago River. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Another issue Happel’s study revealed is the threat posed by high levels of chloride (i.e., salt) in waterways.

“We see spikes of salt in winter months,” he said. Spread liberally on streets, sidewalks and parking lots, salt eventually is washed away into sewers and carried to treatment plants, which are powerless against it.

“Salts are nearly impossible to move out of water,” said Happel.

Any plant, fish or other aquatic species that didn’t evolve in the presence of salt suffers in such conditions, Frisbie said.

The Illinois Pollution Control Board has given municipalities a 15-year grace period to lower the concentration of salt in the region’s waterways.

Friends of the Chicago River, MWRD and other entities have been pushing a “salt smart” campaign to get people to dial back on their use of salt, but it’s been a tough sell, she said.

“Here, we have a long and storied history that Mayor Blandic lost his job because of a snowstorm,” said Frisbie. “Chicago has a propensity for using a ton of salt.”

Though the salt smart message has been embraced by agencies charged with clearing roadways, the tougher nut to crack has been reaching private contractors hired by landlords, condo associations and businesses, as well as individual homeowners.

“It’s very much misunderstood how and when to use salt. The intent is good, but the misapplication is a problem,” she said.

More isn’t better, with a single cup of salt sufficient for 500 square feet, spread evenly as opposed to clumps. “If you see salt, it’s too much,” Frisbie said.

What’s next?

Though Happel’s analysis revealed key role the removal of wastewater pollutants had on fish diversity, algorithms and machine learning can’t predict what it will take to lure thus far reluctant species to the region’s rivers.

“We don’t see gar, we don’t see northern pike, we don’t see sturgeon in downtown Chicago,” he said. “Seeing those species would mean quite a change. Those species are super picky about how they live their lives. So now we look at habitat and what we can provide.”

Floating vegetation, like Shedd’s partnership on the Wild Mile in the North Branch, is one such option. Friends of the Chicago River has been investing in habitat as well, creating hundreds of nesting sites for channel catfish and planting water-willow and lizard’s tail along the North Shore Channel and Little Calumet.

Dam removal has been another piece of the puzzle, increasing the freedom of movement for fish, Frisbie said.

“It’s not that it isn’t complicated,” she said. “But if we collaborate and educate people, that’s how we make the difference.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]