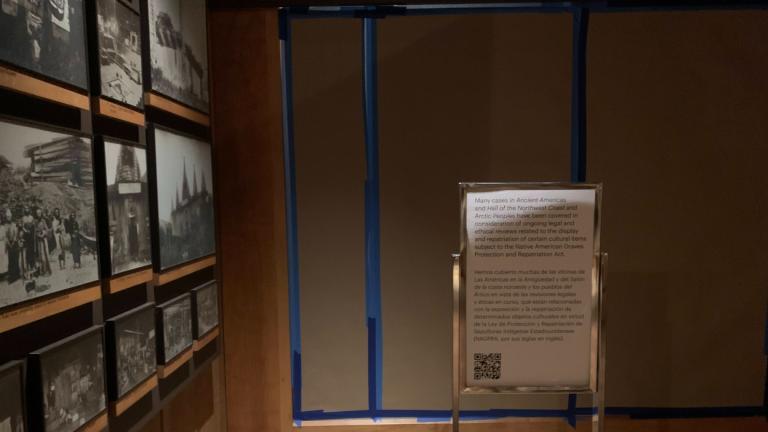

Specimens of the extinct Xerces blue butterfly, in the Field Museum's collection. (Courtesy of Field Museum)

Specimens of the extinct Xerces blue butterfly, in the Field Museum's collection. (Courtesy of Field Museum)

It hasn’t been seen since the 1940s, but the delicate Xerces blue butterfly, famed for its iridescent periwinkle wings, can still get folks to wax poetic.

“When the tiny wings of the last Xerces blue butterfly ceased to flutter, our world grew quieter by a whisper and duller by a hue,” Mark Jerome Walters wrote In an oft-quoted essay mourning extinct species.

Was the elegy misguided?

The Xerces status as a distinct species, as opposed to being a sub-population of another non-extinct butterfly, has been questioned by some for decades.

In a new study published in Biology Letters, researchers at the Field Museum were able to put a definitive end to those doubts, confirming that the Xerces blue was indeed a unique species, albeit one now also confirmed as extinct.

“It’s interesting to reaffirm that what people have been thinking for nearly 100 years is true, that this was a species driven to extinction by human activities,” said Felix Grewe, co-director of the Field’s Grainger Bioinformatics Center and the lead author of the Biology Letters paper on the project.

Grewe collaborated on the study with Corrie Moreau, director of the Cornell University Insect Collections and a former researcher at the Field. Moreau pinched off a piece of abdomen from a 93-year-old Xerces specimen held in the Field’s collection, and the DNA was then sequenced and analyzed at the Field’s labs.

“When this butterfly was collected 93 years ago, nobody was thinking about sequencing its DNA,” Grewe said in a statement. “That’s why we have to keep collecting, for researchers 100 years in the future.”

Why go to such lengths to prove a widely accepted, nearly 100-year-old theory?

Because science matters, and there’s a lot riding on the story of the Xerces.

The Xerces blue, despite its diminutive size, is a giant within the conservation movement, cited as the first case of an insect extinction that can be attributed to urban development.

The butterfly flourished along a patch of sand dunes in the San Francisco Bay area, near the Presidio and what’s now Golden Gate National Recreation Area. As the city grew, the habitat of the Xerces blue was dramatically altered — new foliage introduced in some sections, pavement poured in others — and the butterfly vanished.

In 1971, lepidopterist Robert Michael Pyle founded the Xerces Society, devoted to invertebrate conservation, with the blue butterfly as both its inspiration and literal poster child.

“If we’d found that the Xerces blue wasn’t really an extinct species, it could potentially undermine conservation efforts,” said Moreau. “It’s really terrible that we drove something to extinction, but at the same time what we’re saying is, OK, everything we thought does in fact align with the DNA evidence.”

While the Field team used advances in DNA technology to settle the question over Xerces blue’s extinction, another team of scientists on the West Coast is attempting to resurrect the butterfly.

In recent decades, the Presidio Trust has restored a portion of the Xerces’ native habitat, leading Pyle to speculate about how a butterfly genetically similar to the Xerces might “re-evolve” if it were set loose upon the restored landscape. This “relocation” model, which has succeeded elsewhere, is one way of pulling a low-key “Jurassic Park.” Genetic editing is another option.

The Field team addressed the possibility in their paper.

“Before we start putting a lot of effort into resurrection, let’s put that effort into protecting what’s there and learn from our past mistakes,” Grewe said.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]