A UIC professor has received a grant from NASA to search for "legacy wetlands." (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A UIC professor has received a grant from NASA to search for "legacy wetlands." (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Kimberly Van Meter grew up in Iowa, land of corn and soybeans. But, as the hydrology professor likes to remind people, all that farmland is an illusion.

“The early settlers would talk about being able to ice skate from town to town because there was so much water on the landscape,” said Van Meter, assistant professor of ecohydrology at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The only reason vast swaths of the Midwest aren’t still a swamp today is because a network of underground drainage tiles pulls water out of the land and shoots it down pipes to tributaries and, eventually, the Mississippi River.

“You see farmland and I don’t think we realize what an engineered landscape that farmland is,” said Van Meter.

All that drainage allowed people to grow crops and build cities and houses, but it also came at a cost. Those same wetlands that settlers viewed as an obstacle have benefits scientists only came to understand later, namely their ability to reduce flooding, filter contaminants and, perhaps most importantly, the way they support biodiversity.

“They’re like little Amazon rainforests,” Van Meter said. “There’s a lot of diversity in a wetland.”

The question she’s been asking herself lately is whether there’s a way to strategically reverse-engineer some of the harm drainage has caused to the ecosystem.

NASA, in the form of $374,000 research grant, is going to help her find the answer.

The space agency might seem an odd partner for an earth scientist like Van Meter, but in truth, they’re a natural fit.

“The great thing about NASA is they’re out there on Mars but also they have a big focus on earth research. Those satellites go up and they’re collecting all kinds of data about earth systems,” she said. “We’re in this exciting new period in the hydrology world where we’re thinking about, ‘How can these NASA monitoring projects help us better understand water?’”

What Van Meter’s project proposes is to take NASA’s imaging power and use it to hunt for lost wetlands.

Through a technology known as lidar, NASA has the capability to collect data on topographic shifts across large landscapes. Lidar will not only sense huge mountain peaks, but it will also show subtle depressions in a farmer’s field, which are potential candidates for what Van Meter calls “legacy wetlands.”

Anyone who’s ever driven through farm country has likely noticed these low-lying wet spots from the highway. The thing is, Van Meter is looking for them across the entire upper Mississippi River basin — parts of Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, southern Minnesota and northern Missouri.

“It would be unthinkable to work at this kind of scale without this kind of NASA data,” she said.

Pairing the lidar data on low spots with existing information on an area’s soil composition, “We can say, ‘Those are where those old wetlands are, those wetlands that have drained, that we’ve lost,’” Van Meter said. “We’ve done that in some smaller areas, but in this project, we’ll be creating a map of what all the historical wetlands looked like — their shape, their location — across this whole area.”

The creation of such a map would be exciting enough in itself, but it’s only one aspect of Van Meter’s project.

Her plan is to also use NASA satellite imagery to zero in on how well crops are performing in those legacy wetlands, and compare the yield to adjacent land where there was no wetland.

“Then we can really start saying, maybe it’s not worth it to farm this little piece of land right here. Maybe this is a good place for us to think about restoring a wetland because this farmer isn’t making money from it and it might as well be playing this other role in the landscape,” she said.

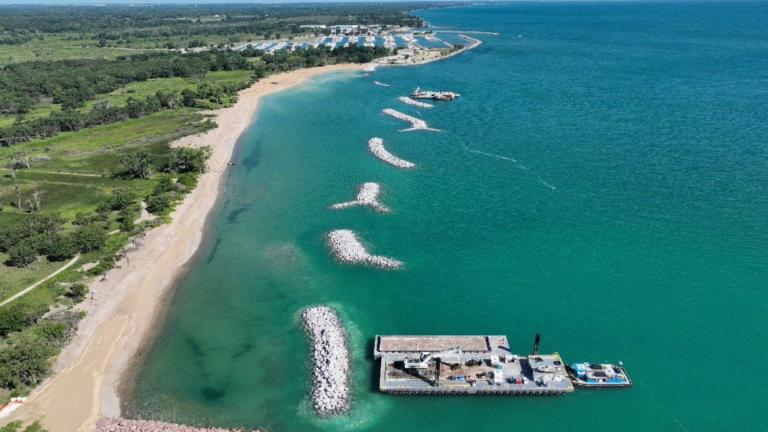

Wetlands were drained to make way for agriculture. In the process, their benefits to the ecosystem were lost, including filtering contaminants and supporting biodiversity. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Wetlands were drained to make way for agriculture. In the process, their benefits to the ecosystem were lost, including filtering contaminants and supporting biodiversity. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

What Van Meter is suggesting is a significant shift in the approach to wetland restoration, much of which is currently ad hoc and often focused on areas that are already fairly natural. Picture instead a systematic, targeted process that zeros in on the nation’s massive agricultural tracts.

“We can be strategic about where wetland restoration happens, and then we can get the most bang for our buck,” said Van Meter.

The added “bang” when it comes to restoring legacy wetlands in the midst of farmland is the impact it can have on water quality, specifically in terms of removing nitrates.

The runoff from nitrogen fertilizer contaminates water locally all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico. Wetlands located in farm fields can filter the runoff, removing the nitrate.

“So not only do you get the benefit of biodiversity — you’re getting more little insects, more pollinators — but you also are getting this water quality benefit,” Van Meter said.

Those benefits are particularly important in the Midwest, with the upper Mississippi River basin contributing the largest amount of nitrate heading down to the gulf, she said. A 20% increase in wetland area could potentially cut the nitrate load pouring into the Mississippi by 40%-50%.

“And that’s huge. That’s huge. We’ve been working on this for decades, and we’re not really seeing any decrease in nitrates going down the Mississippi River basin,” Van Meter said. “I like to talk about, ‘What are the knobs that can be turned?’ And to me, wetlands are a knob that we can turn to actually turn down that nitrate load.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]