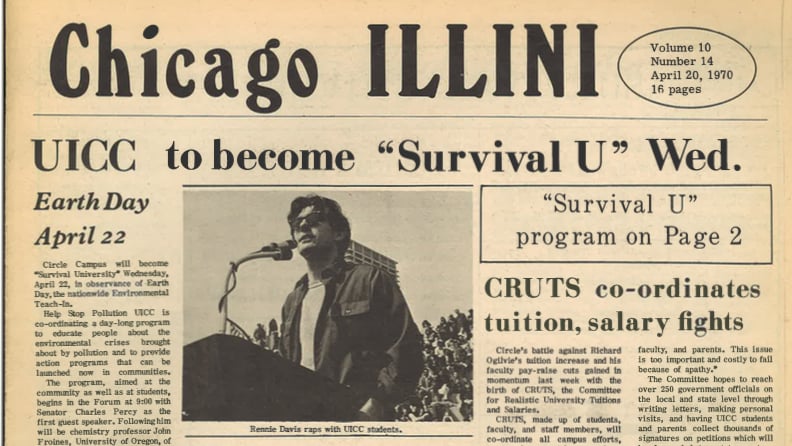

The University of Illinois at Chicago Circle (now UIC) was a hub for the first Earth Day. (Courtesy UIC archives)

The University of Illinois at Chicago Circle (now UIC) was a hub for the first Earth Day. (Courtesy UIC archives)

April 22, 1970, was the kind of spring day Chicago doesn’t enjoy very often.

“It was such a gorgeous day to be outside,” said Karen Furnweger. “It was a beautiful April day.”

A freshman at what was then called the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle (later changed to UIC), Furnweger was the features editor for the school’s independent student newspaper, the Chicago Illini, and had given herself the plum assignment to cover the curiosity known as Earth Day.

“The perfect excuse to take advantage of the event all day,” said Furnweger, who is now the Shedd Aquarium’s editor and content manager.

Billed as a national demonstration/teach-in, Earth Day was founded by Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson, who, as legend has it, was inspired to raise awareness of environmental issues after witnessing the 800-mile oil slick that formed off the coast of California following an oil well blowout.

1970 was still essentially the ‘60s, Furnweger said, and Circle Campus activists embraced the Earth Day cause with the same fervor they had for civil rights, women’s liberation and Vietnam anti-war protests.

Organizers put together a full day of programming, dubbed “Survival University,” and recruited a lineup of speakers that included the Illinois attorney general and Illinois Sen. Charles Percy. Circle faculty from the biology, chemistry, sociology, art and economics departments took part in panel discussions on topics like “Lake Michigan: Too Thick to Drink, Too Thin to Chew.”

“It was a powerful event, it really was a catalyst for people. I know people got charged up, like me, who personally took it to heart," said Furnweger, who took up recycling and made a lifelong commitment to driving fuel-efficient cars. "It was an epiphany for me. I finally felt like there was a movement I belonged to and belonged in.”

Some 600 miles away from Circle Campus in Washington, D.C., the National Mall was the scene of another inaugural Earth Day demonstration. (Twenty million Americans in total would take part in Earth Day activities, or 10% of the population.)

Jerry Adelmann, the longtime president and CEO of the Chicago conservation nonprofit Openlands, was then a student at Georgetown University in 1970.

“I remember kind of going down to the (National) Mall, but I don’t have any clear recollection,” said Adelmann. At the time, he noted, the capital was in a perpetual state of unrest. “There were demonstrations endlessly, one after the other.”

What he is sure of is that Earth Day represented a remarkable moment in American history, one that united fragmented interest groups and cut across political lines. Even then President Richard Nixon got into the spirit of the day, planting a tree on the White House lawn.

“Earth Day kind of brought everyone together,” Adelmann said. “Clearly the ‘70s, that environmental decade, was extraordinary.”

Karen Furnweger bought this pin for a buck at the first Earth Day and wears it every year. "It's the best dollar I ever spent," she said. (Courtesy Karen Furnweger)

Karen Furnweger bought this pin for a buck at the first Earth Day and wears it every year. "It's the best dollar I ever spent," she said. (Courtesy Karen Furnweger)

Immediate outcomes of that first Earth Day included the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and passage of the Clean Water Act. Advocacy and activist groups proliferated: the Natural Resources Defense Council formed in 1970 and Greenpeace followed in 1971.

In Chicago, environmentalists scored an early win when then Mayor Richard J. Daley was forced to scuttle his bid to build a third airport on Lake Michigan. And organizations like Openlands, founded in 1963, dug in to tackle some of the city’s most intractable environmental problems, forming a committee that would eventually become the standalone Friends of the Chicago River.

People today forget how bad things were, Furnweger said.

“Buses were belching black smoke. The air was terrible,” she said. “I think we’ve come a long way. People are driving electric cars now, people are concerned about what they consume. We’ve got river otters in Illinois and fish in the Chicago River.”

Indeed, Chicagoans might be surprised to learn what a global pioneer their city has been in terms of its innovative conservation efforts, Adelmann said.

“Our landscape is subtle, but we have greater biodiversity here than Yellowstone National Park,” he said.

Conservation used to mean fencing off areas and keeping people out, he said. But Chicago’s model, spearheaded by Openlands, which was one of the lead organizers of the city's first Earth Day, has been to connect people to nature, creating green spaces that work for wildlife, plants, waterways and humans.

“There have been a lot of firsts,” Adelmann said of Openlands track record: the first national prairie (Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie), the first heritage corridor (Illinois and Michigan Canal) and even the first inventory of vacant lots, which in turn spawned the creation of the NeighborSpace urban land trust.

Rails-to-trails conversions and wetlands restoration are other areas in which Chicago has taken the lead, he said.

“Chicago has been very creative and also entrepreneurial in responding to challenges,” Adelmann said. “There’s a lot to be proud of. But there’s a lot of work to do.”

Habitat degradation remains an issue, as does air and water pollution, except now the toxins, like nanoplastics, are less obvious, Furnweger said.

And then there’s climate change. That first Earth Day, “we had no clue about climate change,” she said.

Fifty years later, it’s a global crisis in need of a global response. Earth Day 2020 was supposed to galvanize the world in support of saving the planet, instead it got pushed to the back burner by the coronavirus pandemic.

Adelmann, for one, sees the COVID-19 outbreak as both an opportunity for environmentalists to grow their base but also as a danger to the movement’s progress.

On one side of the coin, awareness of the value of the outdoors — nature and open spaces — has never been greater than it is right now, both in terms of physical and mental well-being, he said.

And the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable communities has brought environmental justice — a concept itself pioneered in Chicago by Hazel Johnson at Altgeld Gardens — to the forefront, said Adelmann.

The recent botched demolition of a former coal plant in Little Village, which covered the neighborhood in a plume of dust during the pandemic, gained enormous attention, he said.

“A lot of it was invisible before. Now it’s being talked about, people are getting engaged,” Adelmann said.

At the same time, he said, the Trump administration has chipped away at a host of environmental regulations, with the EPA using the pandemic as justification for giving companies permission to temporarily halt monitoring and recording of pollution. And Adelmann said the push to jump-start the economy is likely to come at an environmental price.

It will be up to organizations like Openlands and a new generation of people like Furnweger to continue the work that Earth Day started: the fight for the planet’s health, which is also the fight for people’s health.

“You see what a natural issue can do, and COVID is tied to nature, it’s not imposed by a dictator,” Adelmann said. “It’s not that hard to say that climate is going to be bigger and we’re not going to have a vaccine.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]