Pot is female. The industry isn’t. (Martijn / Flickr)

Pot is female. The industry isn’t. (Martijn / Flickr)

Did you know that pot is female? It’s true: Cannabis plants have a gender — male and female — and only the females produce large THC-filled buds. The males just sprout little pollen sacs.

So marijuana is female, but the cannabis industry most decidedly is not. In fact, even as more and more states are legalizing recreational use of marijuana, the percentage of women holding executive-level roles within cannabis-related businesses is falling.

In 2015, women could be found in leadership positions at 36% of companies within the industry. Just two years later, that figure had dropped to 27%, according to Marijuana Business Daily. In 2019, women lost even more ground, holding executive positions at just 17% of companies.

Chicago has been no exception.

In November, the first round of “adult use” cannabis licenses were awarded to operators of the city’s medical marijuana dispensaries, and the recipients were overwhelming male and white, prompting outrage from leaders within Chicago’s minority communities.

With the next round of licenses due to be announced by May 1, Ald. Leslie Hairston (5th Ward) called for a hearing, convened Tuesday by City Council’s Committee on Workforce Development, to discuss ways to increase the participation of women in an industry that reported $40 million in sales statewide its first month of legalization.

“It is imperative we expand the role of women, especially women of color,” Hairston said at the hearing’s outset. “How do we change traditional power structures? What are the policies that would encourage women to enter and flourish? What are the barriers? We want this hearing to be the start of the conversation.”

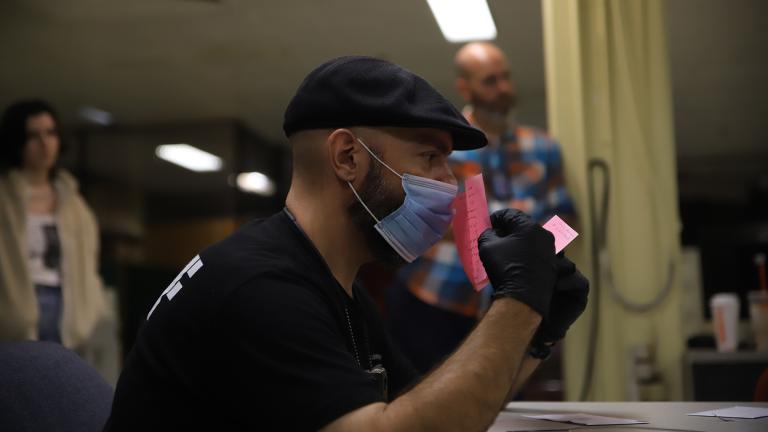

During the course of the three-hour session, committee members heard testimony from a number of women either employed in the industry or attempting to gain a license, and the picture they painted suggests that while legalized cannabis may be an emerging industry, it’s already become as much an old-boys’ network as more established avenues of commerce.

When she first entered the industry on the sales side, Nicole Cordero said she was valued less for her expertise and more for her appearance.

“It’s a common issue,” she said. “Women are oversexualized in order to sell a commodity.”

Cordero has since moved on to become the director of brand strategy for Mission Dispensaries, which operates in South Chicago, but noted that Mission’s hiring and promotion of women is a rarity in the business. In the absence of more female owners, Cordero said, “white, cis male investors will continue to mold cannabis culture.”

Other speakers testified to cultural norms that continue to stigmatize marijuana, and the lack of education not only about its health benefits but the business opportunity presented by the legalization of recreational pot use in Illinois. To borrow a phrase from “Hamilton,” women, particularly women of color, aren’t in the room where discussions about the economic potential of the cannabis industry happen.

“I think a lot of women don’t realize how important this is. This opportunity is once in a lifetime,” said Eva Hernandez, a license applicant from Little Village.

As executive director of Chicago NORML (a chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws), Edie Moore has been spreading the word about cannabis via the kinds of workshops and info sessions she wishes had been available back in 2014, when Illinois issued its first medical cannabis dispensary licenses.

“Cannabis was not on my radar (in 2014),” said Moore, who eventually went on to become one of the original owners of the only majority minority-owned firm to receive an Illinois medical cannabis license. “I have a pretty wide, diverse circle of friends and no one knew.” It was only by “happy circumstance,” she said, that “I realized our state was on the verge of legalizing this.”

Some progress is being made on the education front — Olive-Harvey College has introduced a cannabis dispensary operations curriculum, for example — but the biggest barrier to women holding positions of power in the cannabis industry is the same obstacle they and other minorities have faced since time immemorial: they don’t have the funding.

“It’s not that women aren’t interested in being operators, they lack access to capital,” said Seke Ballard, CEO and founder of Good Tree Capital, which is solely focused on providing loans to cannabis companies.

Cannabis is an incredibly capital-intensive industry, Ballard said, but banks, which provide lending capital to 70% of small businesses, are sitting on the sidelines, creating a gaping funding hole.

Unless a person has wealth of their own to draw on, they need to turn to private lenders, many of whom aren’t interested in financing operators of color or women, said Ballard. Other private financiers often charge predatory interest rates or insist on an equity stake in the company, knowing they have a desperate, captive audience, he added.

Amanda Fox, who co-owns a number of dispensaries in Colorado, told the committee she and her husband had to present their business plan more than 200 times before reeling in a single deep-pocketed investor.

“Raising money is a full-time job,” she said, and that was for a pair of seasoned entrepreneurs with a track record of successful startups.

Coming from a state with a head start in the cannabis industry, Fox shared a pair of sobering statistics: only 2% of marijuana growers in Colorado are women, and only 10% of cannabis executives are female.

“Women have struggled. When I first started, there were a lot of females in the business,” she said, but today there are virtually none. “Cannabis is quickly becoming a male-dominated space.”

What gets lost is the same thing that gets lost every time women are excluded, she said: the female perspective.

“Men and women are different,” Fox said, down to the way they react to strains of cannabis. “Women need to have a seat at the table and we need to be at the head of the table.”

Getting the seat is just the first hurdle to clear. Keeping it will be perhaps the greater challenge.

Illinois’ law was written in such a way to give “bonus points” to social equity license applicants — those who either live in a designated “disproportionally impacted area,” have a low-level drug record or have a close relative with one, or are able to prove that employees hired meet those criteria.

Hundreds of social equity applicants, many of them with women at the helm, are in the running for the next round of licenses to be awarded in May. But how many of those women and minorities are being used as “fronts” for companies that will eventually wind up in the hands of white men? That’s the question council members asked of nearly every speaker at the hearing, a question no one could sufficiently answer.

At the end of hours of testimony and public comment, only one of the hearing’s initial goals had been met, in that barriers had been thoroughly identified. But solutions were scant. Should the council propose a public bank to provide low-interest loans? Clear the way for cannabis street vendors in order to decrease the price of entry? Mandate licensees maintain diversity in their executive staff? Action isn’t likely to come soon enough to assist this first wave of applicants.

Meanwhile, women like Eva Hernandez — “Strong women who are prepared and capable, women who aren’t merely a front,” she said — wait.

They wait to see whether they’ll have an opportunity to prove themselves, or whether the most powerful female force in the cannabis industry remains the plant itself.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]