Life in a 6-by-9 cell, 23 hours a day, for more than 40 years. It’s almost impossible to imagine. But Albert Woodfox doesn’t have to imagine it.

He was one of the so-called Angola Three, held in solitary confinement for decades in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola. Initially locked up on an armed robbery charge, he and two other prisoners were convicted of murdering a guard – a charge the men and their many supporters say was a sham.

“It was only a façade,” Woodfox said. “They had already made up their mind that they were going to charge us because we were politically active in the prison. We were organizing inmates, both black and white. We were taking on the guard brutality, prisoner-on-prisoner crime, administrative corruption.”

Woodfox became an activist, organizing protests within the prison and using the court system. He also spent countless hours reading and educating himself. He also educated his fellow inmates, including teaching another prisoner to read.

“I consider that my greatest accomplishment,” Woodfox said. “He said … I had opened the world to him. It was a tremendous feeling. With all the things I have accomplished, as a social activist in and out of prison, I still haven’t matched that emotional feeling.”

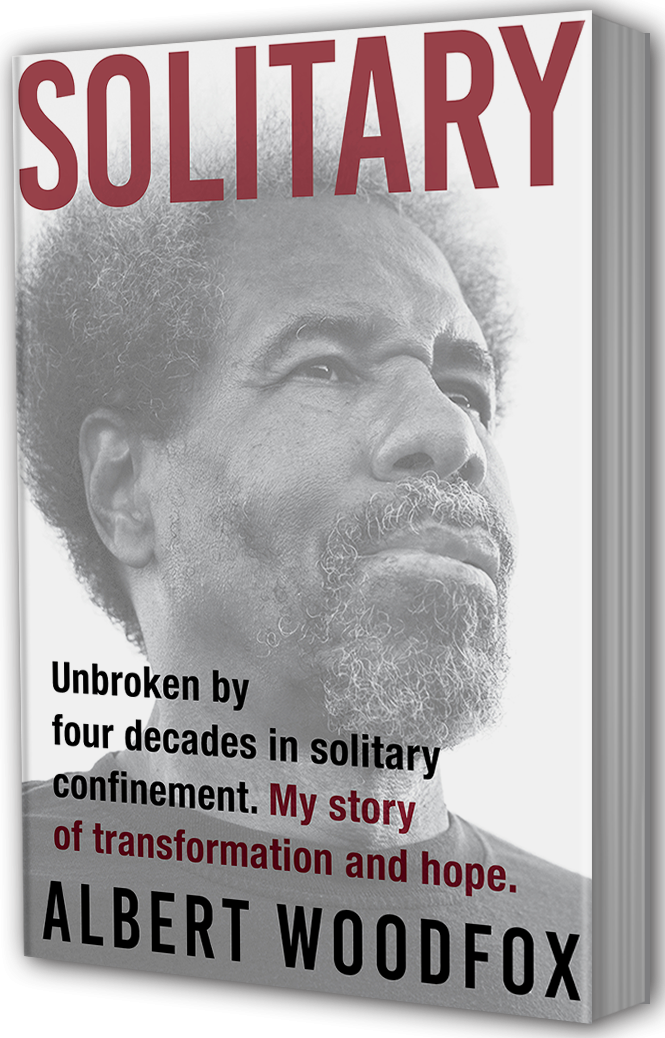

After years of legal wrangling, Woodfox was finally released from prison in 2016. His memoir “Solitary” was published earlier this year. Woodfox says he hopes readers will come away from the book believing “that it is possible to change. That it is possible to reeducate yourself, develop a sense of moral values, principles, sense of self-worth, dignity, pride, self-respect. And to contribute to humanity and society as a whole.”

Below, an excerpt from “Solitary.”

February 19, 2016.

I woke in the dark. Everything I owned fit into two plastic garbage bags in the corner of my cell. “When are these folks gonna let you out,” my mom used to ask me. Today, mom, I thought. The first thing I’d do is go to her grave. For years I lived with the burden of not saying goodbye to her. That was a heavy weight I’d been carrying.

I woke in the dark. Everything I owned fit into two plastic garbage bags in the corner of my cell. “When are these folks gonna let you out,” my mom used to ask me. Today, mom, I thought. The first thing I’d do is go to her grave. For years I lived with the burden of not saying goodbye to her. That was a heavy weight I’d been carrying.

I rose and made my bed, swept and mopped the floor. I took off my sweatpants and folded them, placing them in one of the bags. I put on an orange prison jumpsuit required for my court appearance that morning. A friend had given me street clothes to wear, for later. I laid them out on my bed.

Many people wrote me in prison over the years, asking me how I survived four decades in a single cell, locked down 23 hours a day. I turned my cell into a university, I wrote them, a hall of debate, a law school. By taking a stand and not backing down, I told them. I believed in humanity, I said. I loved myself. The hopelessness, the claustrophobia, the brutality, the fear, I didn’t say. I looked out the window. A news van was parked down the road outside the jail, headlights still on, though it was getting light now. I’ll be able to go anywhere. To see the night sky. I sat back on my bunk and waited.

SOLITARY © 2019 by Albert Woodfox. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Related stories:

In ‘Charged,’ Journalist Looks at Role of Prosecutors in Mass Incarceration

Report: In US Prisons, Women Disciplined More than Men for Minor Offenses

New Partnership Will Give Stateville Inmates a Chance to Earn NU Credits