The Chicago Police Department documented 72 hate crimes in 2016 – a 20-percent spike compared to 2015 and an overall five-year high, according to reporting by the Chicago Tribune.

That increase falls in line with an uptick in hate crimes in other large U.S. cities, such as New York City, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., according to a study released in March by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.

In making sense of the increase, some have pointed to the at-times inflammatory campaign rhetoric of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Betsy Shuman-Moore, director of the Hate Crimes Project at the Chicago Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights, thinks Chicago’s hate crime tally might be even higher due to underreporting by victims or bystanders.

Shuman-Moore has worked for the nonprofit association for 27 years.

“Right now there’s a particular fear and distrust of government and law enforcement,” Shuman-Moore said. “There’s a real reluctance and fear that victims might be punished, or even deported, because of simply reporting a crime.”

The FBI’s latest data on hate crimes is from 2015. That year, the FBI documented 5,850 hate crime incidents throughout the country reported by law enforcement agencies – a 6-percent increase from 2014.

Radio show host and political pundit Charles Butler said the media is to blame for over-reporting hate crimes.

“I see the media selectively talk about hate crimes and try to identify what a hate crime is,” Butler said. “They tried to label Trump as a racist. I know that he’s not a racist. They put all these labels on people that are untrue.”

Since the presidential election, college campuses have emerged as free speech battlegrounds and zones for people to peddle offensive and insensitive ideas.

Last March, several anti-Semitic fliers referencing “Jewish privilege” were distributed inside buildings at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

University of Illinois history professor Adrian Burgos said the individuals who commit such acts have two distinct objectives in mind.

“Spaces of students are targeted both as a way of recruiting students and to intimidate other students,” Burgos said. “They feel the freedom and exercise the freedom to do this. Ultimately, what we don’t know fully is how many individuals are enrolled students, former students and individuals passing through trying to organize.”

Shuman-Moore, Butler and Burgos join host Phil Ponce to discuss the current state of hate crimes and race relations in America.

Related stories:

Vandalism and Bomb Threats Mark Spike in Anti-Semitism

Vandalism and Bomb Threats Mark Spike in Anti-Semitism

March 2: Jewish community centers around the United States have been forced to evacuate in recent weeks after being targeted by bomb threats. What’s behind the uptick in anti-Semitism?

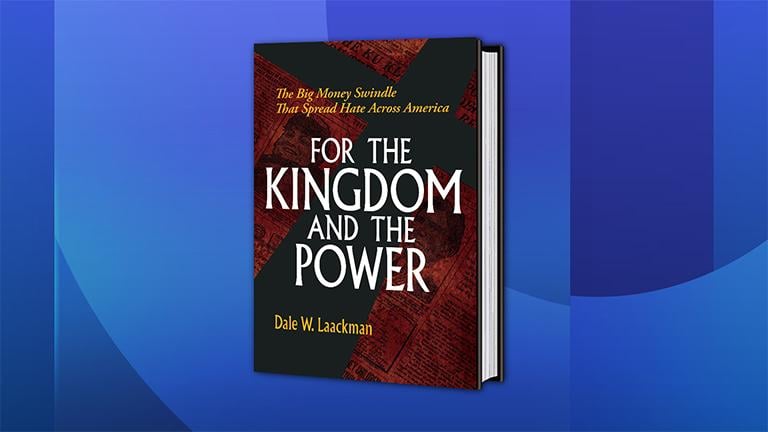

Book Uncovers Story of Spreading Hate Across America

Book Uncovers Story of Spreading Hate Across America

March 31, 2016: In 1920, the Ku Klux Klan was a small, disorganized group with just 3,000 members in Alabama and Georgia. Then a public relations firm saw an opportunity to make a bundle by building the Klan. Dale Laackman's book tells the little-known story.

Former Skinhead Leader Reflects on Personal Transformation

Former Skinhead Leader Reflects on Personal Transformation

May 6, 2015: Christian Picciolini was once a neo-Nazi skinhead leader in Chicago. Today he runs an organization called Life After Hate. Jay Shefsky tells the story of this remarkable transformation.