Chicago has the fifth-highest combined racial and economic segregation of the 100 metropolitan cities studied in “The Cost of Segregation.” (Allen McGregor / Flickr)

Chicago has the fifth-highest combined racial and economic segregation of the 100 metropolitan cities studied in “The Cost of Segregation.” (Allen McGregor / Flickr)

Racial and economic segregation across Chicago impacts economic growth, educational attainment and crime rates—costing the city an estimated $8 billion in annual GDP, according to a report released Tuesday by the Metropolitan Planning Council and Urban Institute.

“It’s not new information that the city of Chicago and the region is segregated. What’s new is that we quantify what it costs everyone, not just those living in predominantly low-income and minority communities,” said Marisa Novara, who helped design and manage “The Cost of Segregation.”

Document: Read the report

According to the report, Chicago has the fifth-highest combined racial and economic segregation levels of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. As a whole, the region would earn $4.4 billion more in income if segregation levels were reduced to the national median.

Document: Read the report

According to the report, Chicago has the fifth-highest combined racial and economic segregation levels of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. As a whole, the region would earn $4.4 billion more in income if segregation levels were reduced to the national median.

Homicide rates would be reduced by 30 percent if the city’s segregation landscape mirrored the national median, according to the report. That equates to 229 lives saved in 2016, and hundreds of millions of dollars in policing and corrections costs, the report states.

High homicide rates have also been linked to dwindling populations in cities. Chicago ranked last in population growth in 2015 among the nation’s 10 largest cities.

In terms of education, the report states that 83,000 more area residents would have bachelor’s degrees if segregation levels were reduced to the national median. This figure represents a $90 billion loss in lifetime earnings, the report finds, based on current earning gaps between those with high school diplomas and bachelor’s degrees.

![]()

“There’s a lot of fear that comes from lack of familiarity that’s driven by segregation.”

–Marisa Novara

Though the region has made improvements in economic and racial segregation between 1990 and 2010, it still lags behind.

The report predicts that if the region continues along the same course, it will take 30 years for the city to reach the national median level of segregation among Latinos and whites. The segregation of African-Americans and whites wouldn’t reach the national median level until 2070.

“When we have the segregation levels that we have, it’s very easy to lump problems that we see to certain populations and make it easy not to interact with those parts of the city,” Novara said. “This leads to a lack of understanding that really forms a lot of what we see today.”

![]()

The report concludes phase one of the Metropolitan Planning Council and Urban Institute’s two-year project, which was conceived when the city re-examined its Affordable Requirements Ordinance in 2014. Novara, who was working on that ordinance, noticed that developers, city officials and housing advocates had different ideas about the profitability and true cost of building low-income housing.

“We didn’t have a good sense of what our status quo cost us,” Novara said.

Along with a group of advisors, the two organizations will now identify and propose policies to accelerate desegregation in the Chicago region.

“I certainly see this as a major part of our work in the future, reframing how we approach policies in this region,” Novara said.

Related stories:

Urban League Research Highlights Ongoing Racial Disparity in Education

Urban League Research Highlights Ongoing Racial Disparity in Education

March 2: A report released this week by the Chicago Urban League shows minority students in the state are still as likely to attend a racially segregated school today as they would have been 60 years ago.

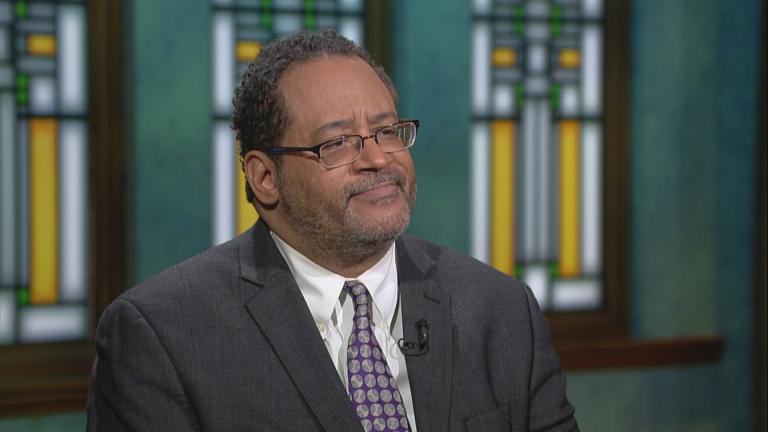

‘Sermon to White America’ Calls for Meaningful Action on Racial Inequality

‘Sermon to White America’ Calls for Meaningful Action on Racial Inequality

Jan. 25: Author Michael Eric Dyson on the challenges faced by black Americans, and why it’s up to whites to address racial inequality.

Segregation and Racial Barriers on Chicago's South Side

Segregation and Racial Barriers on Chicago's South Side

March 23, 2016: A new book by Natalie Moore about the South Side blends personal history with investigative reporting to tell the story of a segregated city and misunderstood neighborhoods.