In the late 1800s, France was the birthplace of two art genres that transformed the visual landscape. One was impressionism. The other might be regarded as more pedestrian – but that was the target audience. It was the art of posters used primarily for street advertising. And a new exhibition at the Driehaus Museum showcases how those posters were not only eye-catching ads but fine art as well.

Join us for a behind-the-scenes look at the exhibition, “L’Affichomania: The Passion for French Posters.” It’s on display at the Driehaus Museum through January 2018.

TRANSCRIPT

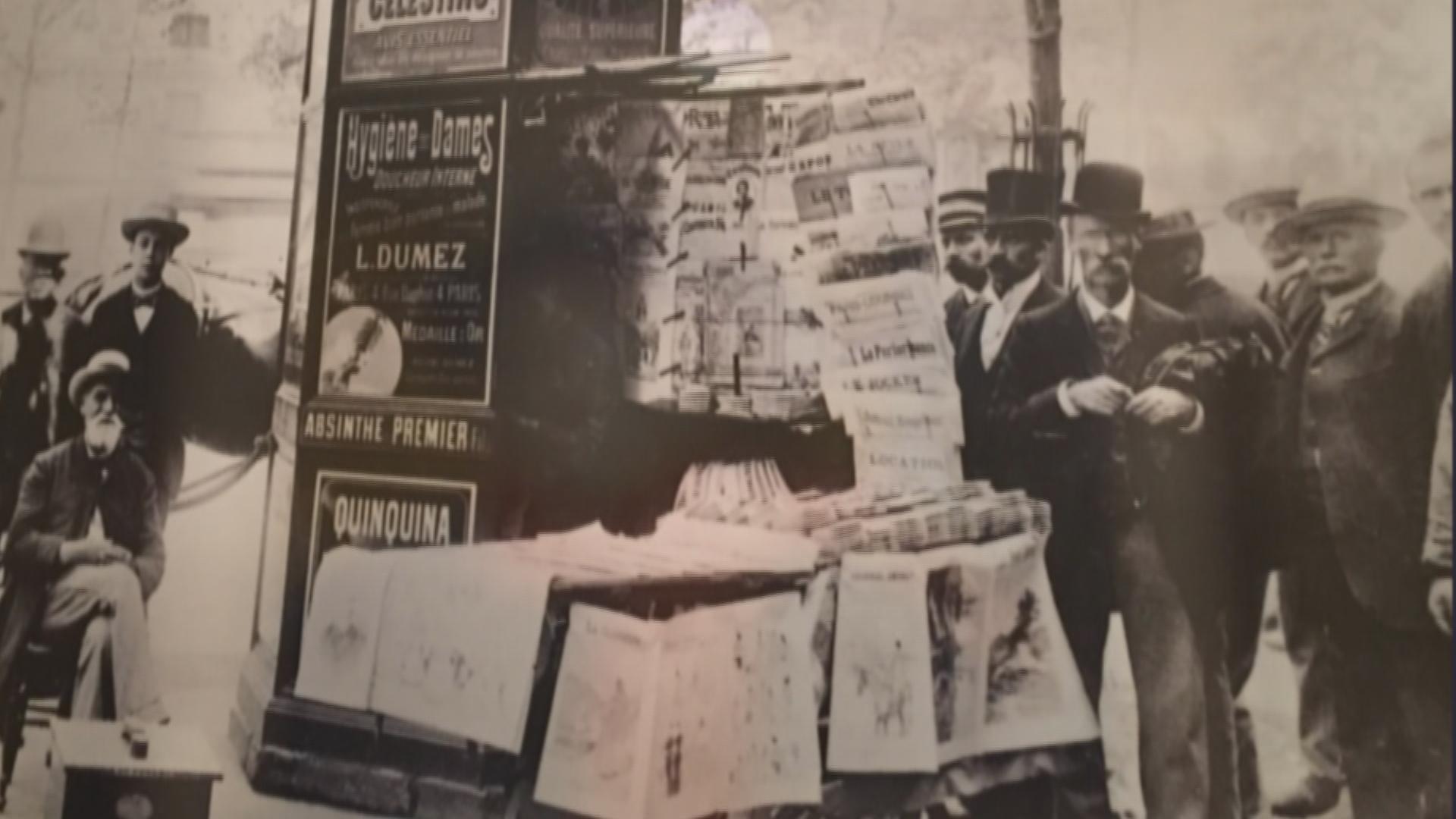

Eddie Arruza: This was Paris at the turn of the 20th century. La belle epoch was at its peak and the City of Light had become the art capital of the world. Art was everywhere in Paris. Along the famed avenues, posters – or affiches – were plastered on walls and kiosks. And they were sensational – in more than one way.

Jeannine Falino, curator at the Driehaus Museum: Posters became the rage for collecting and there were people out there tearing them off the walls and trading them secretly and privately and it was indeed a passion.

Arruza: Or a mania, an affichomania. That is the name of a new exhibit of French belle epoque posters at Chicago’s Driehaus Museum; a collection representing five of the most renowned affiches artists of the era.

The most famous of them all is Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the 4-foot-8-inch giant of the Parisian art scene. He was also well known in the bohemian and cabaret scenes which he immortalized in posters for the famed Moulin Rouge. One of his best known featured La Goulou the "Queen of Montmartre" who tended to show a lot of flesh while performing the cancan. It left some viewers dizzy.

Falino: There are these yellow globes in the lower left-hand corner, and those are the lights. So imaging if you’re sort of drinking, and dancing, and drinking and dancing, and things are starting to spin a little bit. That’s the atmosphere he’s trying to create there.

Arruza: Posters had long been used for advertising but they were wordy, black-and-white affairs until about 1870. That’s when technical advancements in printing captured the imagination of the Parisian-born Jules Chéret, one of the pioneers of the modern poster.

Falino: It was Jules Cheret who saw the potential of what was a commercial process called chromolithography – typically used to copy historic images – and he realized that it had true artistic potential.

Arruza: The melding of commerce and art through the new printing method gave birth to modern advertising. Businesses quickly realized how effective eye-catching posters could be, and soon everything from shoe polish to the latest telecommunication inventions were being hawked in glorious ads designed by leading artists.

Jules Chéret received many commissions. One of his most famous posters was of a dancer by the name of Loie Fuller. Fuller was born in what is now Hinsdale, Illinois. But she had ambition and talent that led her all the way to the Folies Bergère.

She also found a wildly successful gimmick: a serpentine dance in which she employed the new invention of multicolored lights. It dazzled Parisians and Jules Chéret.

Falino: Because she was shown in so many different colors you can actually purchase this poster in four different color waves. And Cheret, being a master of color, he knew how to do that really, really beautifully.

Arruza: Alphonse Mucha was born in what is now the Czech Republic. But like many aspiring artists of the belle epoch, he made his way to Paris where he was a starving artist until one fateful day.

Falino: The great Sarah Bernhardt – the great French tragedian actress – came into a shop where he was hanging out, waiting for a job, and said she needed a new poster for the play “Desmonda” and he produced this supersized image that’s very tall – elongated image – that turned out to be a huge hit and it was so successful that she retained him for many years and it really established his claim to fame and led to a very successful career.

Arruza: Mucha’s distinctive style featuring beautiful women with flowing hair and crowned with a halo launched what became known as art nouveau. Parisians loved it and Mucha capitalized on it. Not only did his posters sell like hot crepes, but his works, like other popular affiches artists, were turned into everything from calendars to postcards and even menus.

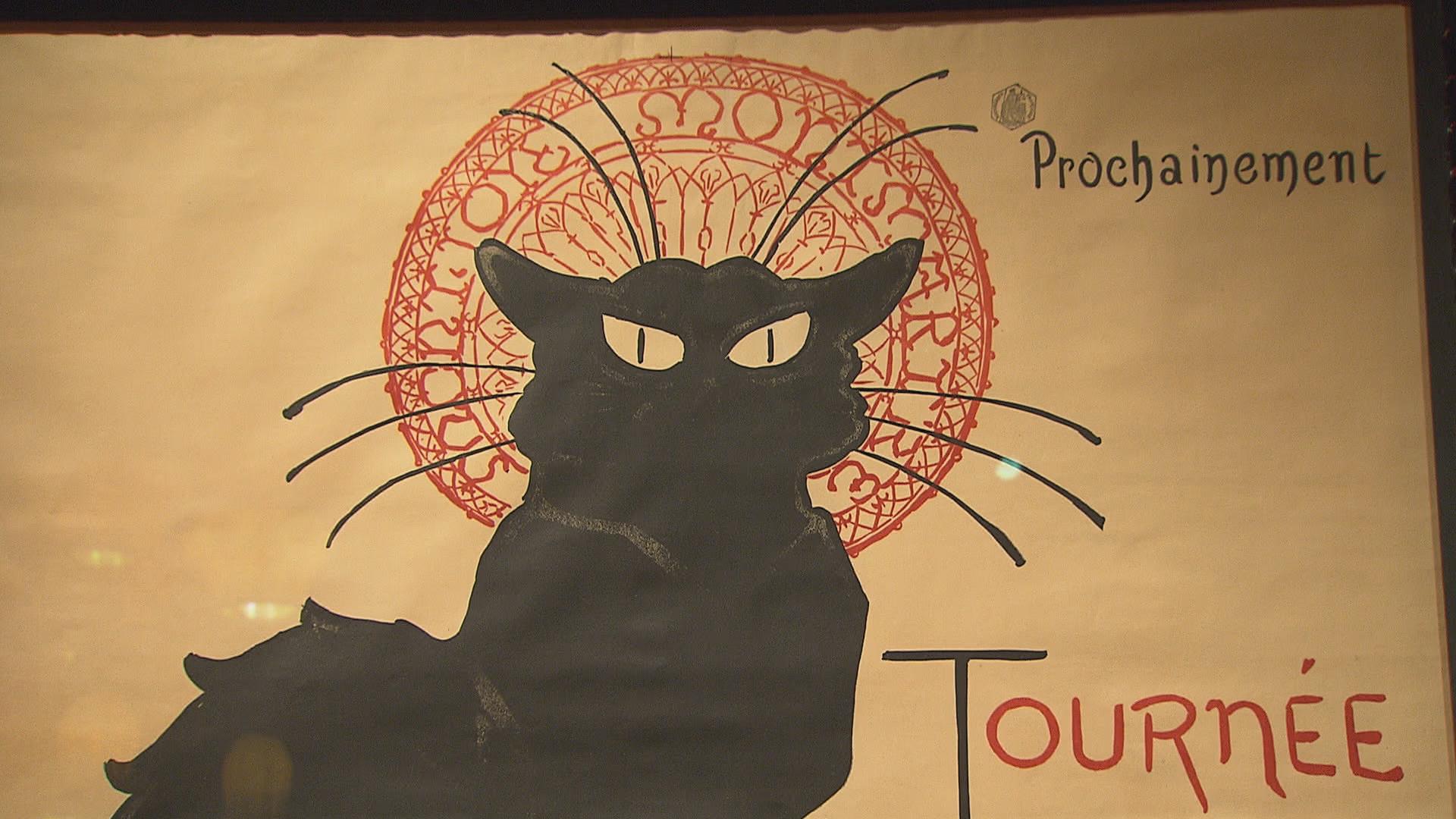

But the French poster that remains a best seller to this day is one by Theophile Steinlen. La Chat Noir – or the Black Cat – was a popular hangout in Paris’ bohemian Montmartre district. But Steinlen also did a little skewering in his famous advertisement.

Falino: This scary black cat who doesn’t look like much of an angel is carrying this halo because Steinlen is making fun of the great Alphonse Mucha.

Arruza: All of the posters in “L’Affichomania” come from a vast collection belonging to the museum’s namesake, Richard Driehaus. He even purchased some just for the exhibit, demonstrating that the mania for belle advertisements has not subsided.

Related stories:

Meet Patsy McNasty, Notebaert Nature Museum’s Alligator Snapping Turtle

Meet Patsy McNasty, Notebaert Nature Museum’s Alligator Snapping Turtle

Jan. 20: Alligator snapping turtle Patsy McNasty moved into a new 300-gallon tank this week at Chicago's Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, where visitors attended a “housewarming” event for the 14-pound turtle.

Kurt Vonnegut Artwork Finds New Home at Chicago Veterans Museum

Kurt Vonnegut Artwork Finds New Home at Chicago Veterans Museum

Jan. 12: We speak with the president of the National Veterans Art Museum about a new exhibition of sketches by the acclaimed author of “Slaughterhouse Five.”

Dec. 30: Beginning Monday, city residents under the age of 18 will no longer be required to pay the $14 admission fee at the museum in Grant Park thanks to a gift from a pair of Kansas donors.