The Bunte Brothers Candy Company concocted confections for generations of Chicagoans. Geoffrey Baer reveals Chicago’s sweet history as a candy capital and more in tonight’s Ask Geoffrey.

Where was the Bunte Candy Company located and what happened to it? When I was a small boy back in the 1930s my dad would get a discount letter from his company at Christmastime, and we would drive to the Bunte factory and buy a five pound box of chocolate candy. It seemed like a huge box. I recall it had the name Bunte on it and a picture of a large cocoa bean. We would open it and have a sample on the drive home.

-Ken Kitzing, Mt. Prospect

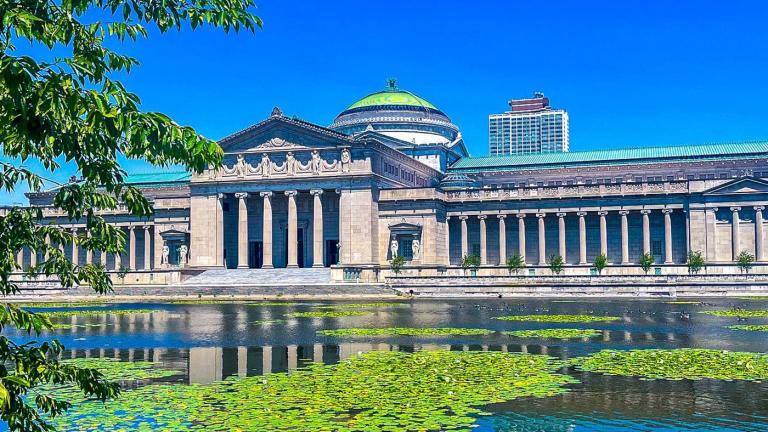

Bunte Factory in 1920

The Bunte Brothers Candy Company was one of the many candy companies that made Chicago the candy capital of the country. Although the plant closed in 1961, it remained standing as Westinghouse High School until 2009.

Bunte Factory in 1920

The Bunte Brothers Candy Company was one of the many candy companies that made Chicago the candy capital of the country. Although the plant closed in 1961, it remained standing as Westinghouse High School until 2009.

Bunte was started in 1876 by brothers Ferdinand and Gustav Bunte and their partner Charles Spoehr. Bunte Bros and Spoehr Candy’s original factory was on South State Street. After a few years, Ferdinand’s son Theodore took charge of the business, and it really began to take off, with annual sales over $3 million and 1,200 employees.

Bunte Brothers had a knack not only for creating delicious and varied types of candy, but also for branding each type with a different name and advertising them separately. According to one article, at its peak Bunte Brothers Candy produced 1,500 kinds of confections.

Bunte Candy Chocolates

They built a reputation for their hard candies, including the fruit-filled hard candy Diana Stuft Confections. They also claimed to have produced the first chocolate covered candy bar. It was the marshmallow and maple Tango candy bar. And the Bunte cough drops were a big seller for “stopping that tickling cough.” In 1917, the company purchased 14 acres on the West Side of Chicago at Franklin and Homan avenues to build a sprawling factory, enabling them to quadruple their production.

In addition to being in a convenient location for transportation, the modern new factory boasted athletic fields, recreation rooms, and shower and manicure parlors for its employees. Bunte made candy there for decades until it was purchased by a Missouri candy company in 1954. Bunte changed hands a few times after that – but through a series of acquisitions it wound up owned by Farley’s and Sathers, which is owned by the same owners as the Ferrara Pan Candy Company of Forest Park, Ill.

The West Side factory remained Westinghouse High School until 2009, when a new facility was built and the site of the old factory became the school’s football field. And while Bunte Brothers Candy may be gone, their legacy lives on in the candy world through a few former employees who went on to create candies we still know and love today. The Oh Henry bar’s creator George Williamson was a Bunte alumnus as was J.R. Holloway, inventor of Milk Duds.

Most notably, Chicagoan Emil Brach founded candy titan Brach’s Candy after his start at Bunte. The massive Brach’s “Palace of Sweets” factory was a fixture on the west side until it was finally shuttered in 2003 after 76 years of candy making.

Fans of the Batman movie, "The Dark Knight," will remember how the old Brach’s factory went out with a bang. The moviemakers dressed up the old parking deck as a hospital which was blown up by the Joker .

The book “The Longest Day” mentions that top secret documents about D-Day plans were revealed at Chicago’s central Post Office. What happened?

-Marc Vitali, Oak Park

D-Day Illustration

The 60th anniversary of D-Day, the Allied landing at Normandy on June 6, 1944 during World War II, was just last week. And Cornelius Ryan’s book "The Longest Day" is the definitive recounting of the events surrounding D-Day.

D-Day Illustration

The 60th anniversary of D-Day, the Allied landing at Normandy on June 6, 1944 during World War II, was just last week. And Cornelius Ryan’s book "The Longest Day" is the definitive recounting of the events surrounding D-Day.

The amphibious landing was an intricately choreographed maneuver called Operation Overlord that had been in planning for many months. As the saying goes, loose lips sink ships, so document access and security was tightly controlled. But it wasn’t tight enough to stop every leak.

We talked to our friends at the Pritzker Military Library, who dug up the details on this incident. In March 1944, a poorly-packaged set of top secret documents burst open on the sorting table at the old Chicago central post office and federal building. The package had been sent by U.S. Army Sergeant Thomas P. Kane, an ordnance supply secretary in London. Sgt. Kane, who was of German descent, sent the package to his sister’s address in a predominantly German Chicago neighborhood.

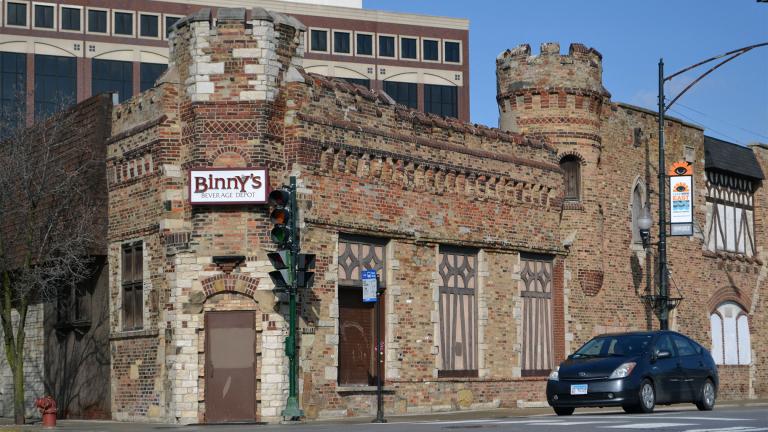

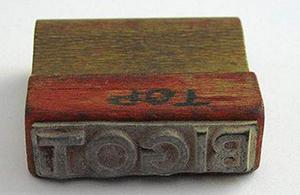

BIGOT Stamp

A number of sorters saw the papers, which were stamped Top Secret and BIGOT. BIGOT stood for British Invasion of German Occupied Territory and was used to stamp all papers and files connected to Operation Overlord. The BIGOT papers in question included the target date and landing beaches of the invasion as well as a schedule for the build-up and breakout. The alarmed postal supervisors called the FBI, which brought a horde of federal investigators to the post office to question the sorters and tell them to forget they saw anything. They were also kept under surveillance.

BIGOT Stamp

A number of sorters saw the papers, which were stamped Top Secret and BIGOT. BIGOT stood for British Invasion of German Occupied Territory and was used to stamp all papers and files connected to Operation Overlord. The BIGOT papers in question included the target date and landing beaches of the invasion as well as a schedule for the build-up and breakout. The alarmed postal supervisors called the FBI, which brought a horde of federal investigators to the post office to question the sorters and tell them to forget they saw anything. They were also kept under surveillance.

The investigators also questioned the sergeant’s sister, who of course knew nothing about the papers or why they had been sent to her, but she did recognize the handwriting on the envelope as that of her brother’s. Kane had sent the package to the Ordnance Division, G-4, but for some reason used his sister’s address. The only explanation he could give was that his sister had been ill and she was on his mind.

While it was quickly determined that the sergeant was not a spy, Sgt. Kane was still kept under observation, had his phone tapped, and was confined to quarters for the following six weeks until D-Day was over. And the rest, as they say, is history.

I heard that there used to be a sausage factory in Lakeview, and the owner murdered and cut up his wife and made her into sausages. Is this true?

-Alan Snopek, West Dundee

Well, this one is mostly true.

Adolph Luetgert's Mugshot

There was a sausage factory in Lakeview where the owner, Adolph, did murder his wife Louisa in 1897. But he didn’t make her into sausages, thankfully. The grisly story is documented in Robert Loerzel’s book “Alchemy of Bones.”

The murderer was a German immigrant who came to the U.S. as a teenager in the 1860s. After working various jobs for a few years he had saved up enough money to open his own business, the A.L. Luetgert Sausage and Packing Company, located at Diversey and Hermitage. Louisa was his second wife, whom he married in 1878 just months after his first wife died.

In May 1897, Louisa Luetgert disappeared. Adolph told their children that their mother had gone to visit her sister but had never come back. A few days later, Louisa’s brother reported the disappearance to the police, and Adolph claimed she had run off with another man.

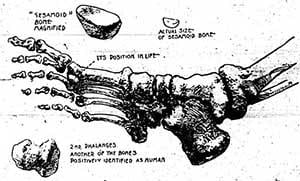

Evidence

The police quickly learned that the Luetgerts fought frequently, sometimes physically. Then it came to light that Louisa was seen going into the factory with Adolph the night she disappeared. The additional discovery of Luetgart’s purchases of arsenic and potash the day before the murder was even more damning, particularly since the factory had been closed for several weeks for reorganization. Police searched the furnaces of the factory, where they found two of Louisa’s rings – one initialed L.L. – and bone fragments in a vat.

Evidence

The police quickly learned that the Luetgerts fought frequently, sometimes physically. Then it came to light that Louisa was seen going into the factory with Adolph the night she disappeared. The additional discovery of Luetgart’s purchases of arsenic and potash the day before the murder was even more damning, particularly since the factory had been closed for several weeks for reorganization. Police searched the furnaces of the factory, where they found two of Louisa’s rings – one initialed L.L. – and bone fragments in a vat.

Adolph was arrested for murder and brought to trial. The first trial ended in a hung jury.

But Adolph was convicted on retrial in 1898 when the prosecution used an anthropologist from the Field Museum to present forensic evidence that the bones found in the vat were human, making it one of the earliest trials to use forensic experts. Adolph Luetgert was sentenced to life in prison, he died there just a year later in 1899 at age 54.

The sausage factory is still standing, though – and people live there!

A 1904 fire destroyed the inside of the building, but the external structure remains and the interior has been rebuilt as condominiums. Some even say that Louisa’s ghost still haunts the area.