Chicago Police Department’s stop-and-frisk practices, known formally as investigative stops, could soon have court oversight for the first time.

The city and the Illinois Attorney General’s Office negotiated an agreement to shift oversight of these stops into a consent decree governing the department.

But during a public hearing earlier this week, civil rights and police accountability groups said that deal isn’t enough.

“It potentially could be great because it is going to be in a transparent way,” said Michelle Garcia, deputy legal director at ACLU of Illinois. “But right now, the current stipulation was negotiated without community input. The stipulation doesn’t meet constitutional muster. They have said they’re only prohibiting when a police officer stops someone solely because of their race. Well, the equal protection clause, the constitution says, look, race only has to be a motivating factor, which means that the way the stipulation is working, an officer could say, well, I stopped them because they’re Black and it’s a high crime area, and they could get away with it.”

Eddie Johnson, former Chicago Police superintendent from 2016 to 2019, said police have since moved away from these stop-and-frisk practices.

“You have to look at the victimization of the areas where these cops are patrolling,” Johnson said. “So if I’m a Black man and I’ve been a victim of a crime and I say to the officer, no matter what color that officer is, and I say it was a male Black wearing so and so, then those cops that get that call are going to be looking for a person that matches that description. Now being a former cop myself, I know that sometimes when people perpetrate crimes, they will start discarding clothing or put on different clothing. So that’s what the premise of how these investigative stops are supposed to go.”

The ACLU reached a settlement with CPD in 2015 that resulted in a decline in pedestrians being stopped and frisked but saw an uptick in traffic stops.

“As a result of the monitoring of the settlement agreement, the numbers went down to about 69,000 stop-and-frisks in 2022,” Garcia said. “It’s still too high. The data is telling us that what CPD did is they switched their practices when they were being monitored to stopping cars and pulling drivers. That number has gone up to the hundreds of thousands.”

Meanwhile, the consent decree that CPD is still under was reached after a 2016 U.S. Department of Justice investigation determined a pattern of racial bias in CPD’s practices, following the release of video of Laquan McDonald being fatally shot by a Chicago officer.

Darrell Dacres, who was elected to the 20th Police District Council, said he’s been stopped two to three times per week on average from his youth all the way to adulthood.

“I was pulled over for stop-and-frisk when I was leaving from grammar school, to high school as a young adult, before I became a working professional in a violence prevention program,” Dacres said.

Dacres is program manager for Communities Partnering 4 Peace and violence prevention director at One North Side.

He said the police encounters he’s been in have normally been nothing short of physical.

“I remember situations where they threw all of my bookbag, all my homework and school supplies on the floor, basically told me to get it, told me to spread my legs, and touched me inappropriately,” Dacres said. “And that was common practice as a child. I didn’t even know that that was illegal, some of the things they did. It was demeaning in a way that was irreparable.”

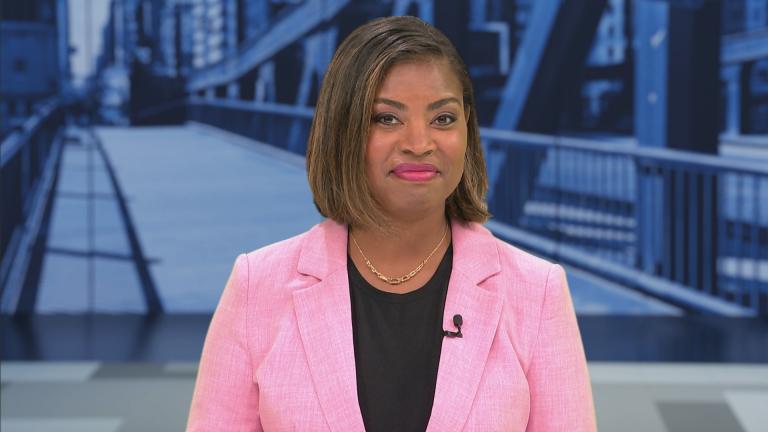

The Rev. Waltrina Middleton, executive director of the Community Renewal Society, spoke at the virtual hearing this week before U.S. District Judge Rebecca Pallmeyer, chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois.

Similar to Dacres, Middleton said these stop-and-frisk encounters have been traumatizing for people in her community.

“We have to think about the whole person and the sanctity of life,” Middleton said. “I think that’s the heart of what we’re trying to get at here when people are afraid to walk in their communities, when they’re afraid to get in the car and actually have a nice car and drive. They’re afraid to sit on their front porch, they’re afraid to just be human. It’s really important for us to really consider the voices and the narratives especially when they’re saying that this is supposed to be a tactic that will be preventative. But if it’s not resulting in finding guns and finding drugs, then why is this practice necessary when it’s actually creating more harm than good.”

Pallmeyer could approve the proposal to merge the stop-and-frisk settlement with the consent decree as is, or she could direct the parties to renegotiate. Pallmeyer did not provide a timeline as of the taping of this interview.