Late last month, 26 current and former employees of a Joliet Amazon warehouse accused the company of allowing a racially hostile work environment. They’ve since been joined by a dozen more workers, who’ve filed charges with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that outline racist death threats against Black employees – and some of those employees also say they’ve faced retaliation from Amazon since speaking out.

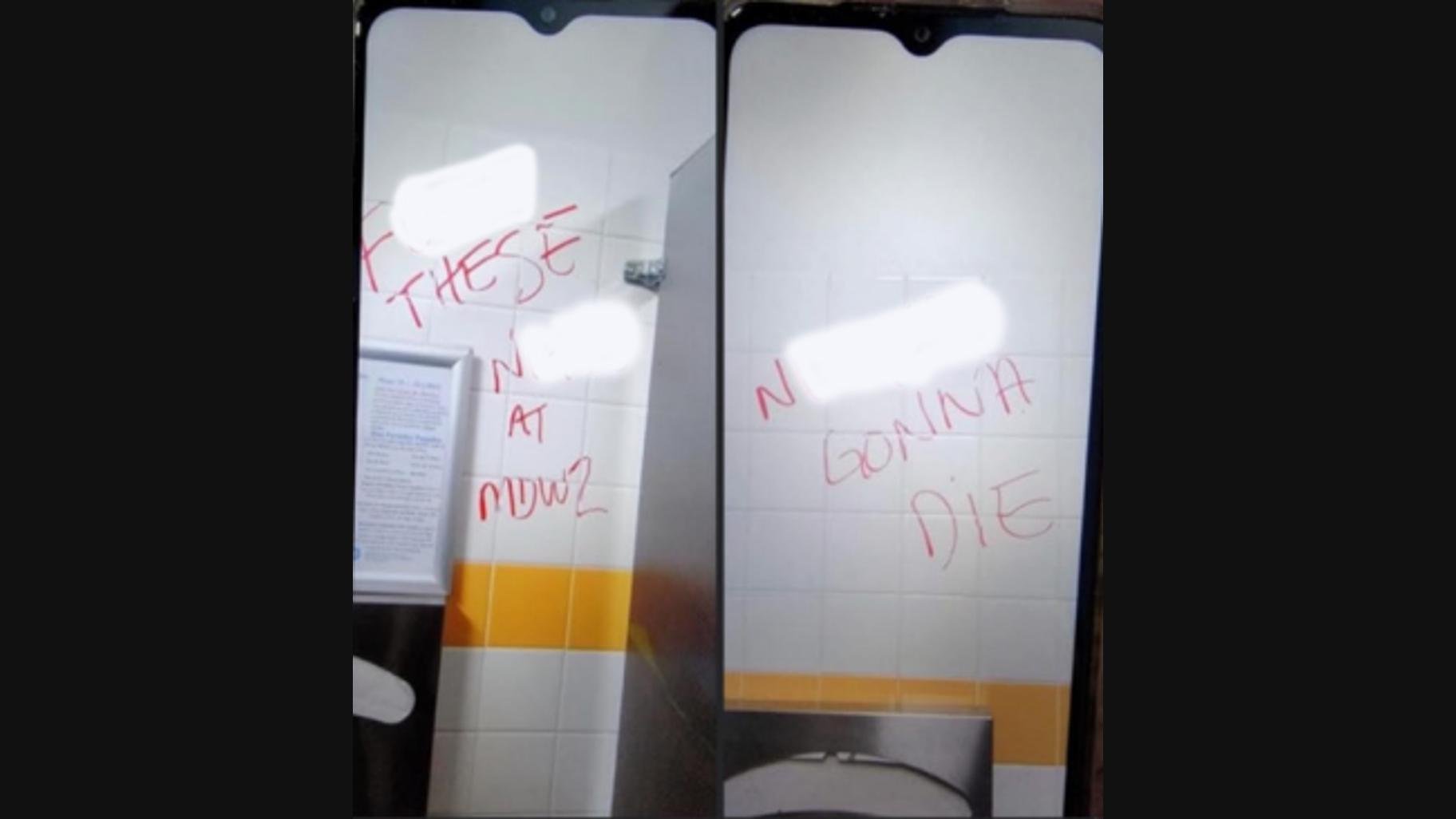

On May 25 – just days after the grocery store mass shooting in Buffalo that’s believed to have targeted Black residents – employees at Amazon’s MDW2 distribution warehouse in Joliet say they found graffiti threatening the lives of Black workers.

“We were told that we could go home with no pay … or we could stay there and keep working,” said former Amazon employee Tori Davis. “We were put in a predicament where we still were in fear every day.”

Workers say Amazon didn’t send a message to employees until nearly 24 hours after the threat was found. And Tori Davis says she was fired after talking with coworkers and demanding action from management.

“We’re not going away until they take this seriously,” said attorney Tamara Holder, who represents the workers in their complaint to the EEOC. She’s since taken on clients at an adjacent Amazon facility in Joliet, MDW4. The graffiti isn’t the only instance of discrimination alleged in the charges.

“Men wearing Confederate flag outfits in the workplace with impunity. Complaints from workers about other workers using the N-word with impunity,” Holder said.

An Amazon spokesperson told WTTW News, “Amazon works hard to protect our employees from any form of discrimination and to provide an environment where employees feel safe. Hate or racism have no place in our society and are certainly not tolerated by Amazon.”

An image included in an EEOC complaint against Amazon shows racial slurs written in a bathroom of the Joliet facility. The racial slurs have been blurred out by WTTW News. (Complaint Provided)

An image included in an EEOC complaint against Amazon shows racial slurs written in a bathroom of the Joliet facility. The racial slurs have been blurred out by WTTW News. (Complaint Provided)

Holder also says Amazon has threatened and fired workers who have spoken out, saying they violated a confidentiality agreement they signed upon hiring.

“The contract is written for somebody who would have trade secrets,” Holder said. “This confidentiality agreement was not made for low-wage warehouse workers. But I believe it’s a tool to silence those workers.”

Nicole Porter, a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law, says confidentiality agreements are a widely used method for companies to protect their trade secrets from competitors.

“If (they) have special procedures that have turned out to be very efficient and effective, you’re not allowed to talk about any of that,” Porter said. “Lots of employers do have employees sign confidentiality agreements, that’s actually quite common.”

But Porter says they can’t be used to stop employees from speaking out about their workplace. As for the EEOC charges, among other things the plaintiffs have to prove the racism was pervasive, unwelcome, and that the company failed to act. But it could be a long legal road ahead.

“The EEOC has the opportunity to investigate – and something, I think, like this where it’s several plaintiffs complaining about it, the EEOC will take that more seriously than they might just one individual employee bringing a claim,” Porter said.

The EEOC might file a lawsuit, it might call for mediation, or it might leave it to the plaintiffs to sue. As for the threats workers say they’ve faced for speaking out: “The employer cannot retaliate against any of the employees that filed the charge simply because they filed a charge, (but) proving that causation piece is sometimes difficult,” Porter said.

“Workers want to do this work, they want a good paying job, (and) they want to get home safely at the end of day,” said Marcos Ceniceros, executive director of the Will County-based nonprofit workers center Warehouse Workers for Justice. “But we need to see some accountability from these companies.”

After the death threats, Warehouse Workers for Justice worked with Amazon employees to publicize the incident and bring their concerns to management.

“Talking to more workers at MDW2, (we discovered) a whole host of health and safety issues workers had concerns about, and what workers felt was inadequate pay,” said organizer Tommy Carden.

Given the explosion of Amazon facilities and other warehouses in recent years, Ceniceros says his organization has a lot to tackle.

“Warehousing is the number one employer in the region, but we see that what does not get better are the working conditions – in fact, they’re getting worse,” Ceniceros said. “It’s important for us to do this work.”

And when it comes to the EEOC charges, Holder says: “We are going to continue to gather as much information as it takes to make sure Amazon listens to us and fixes this work environment.”

An Amazon spokesperson did not respond to follow-up questions about worker claims of retaliation or the company’s confidentiality agreement.

Contact Nick Blumberg: [email protected] | (773) 509-5434 | @ndblumberg