Charlotte Pavelka and Doug Reitz on bird monitoring duty, June 2022, at Captain Daniel Wright Woods. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Charlotte Pavelka and Doug Reitz on bird monitoring duty, June 2022, at Captain Daniel Wright Woods. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

On a morning in early June, at an hour when most Chicagoans were still hitting the snooze button, Charlotte Pavelka and her husband Doug Reitz had already ventured into the forest at Captain Daniel Wright Woods, some 35 miles northwest of Chicago.

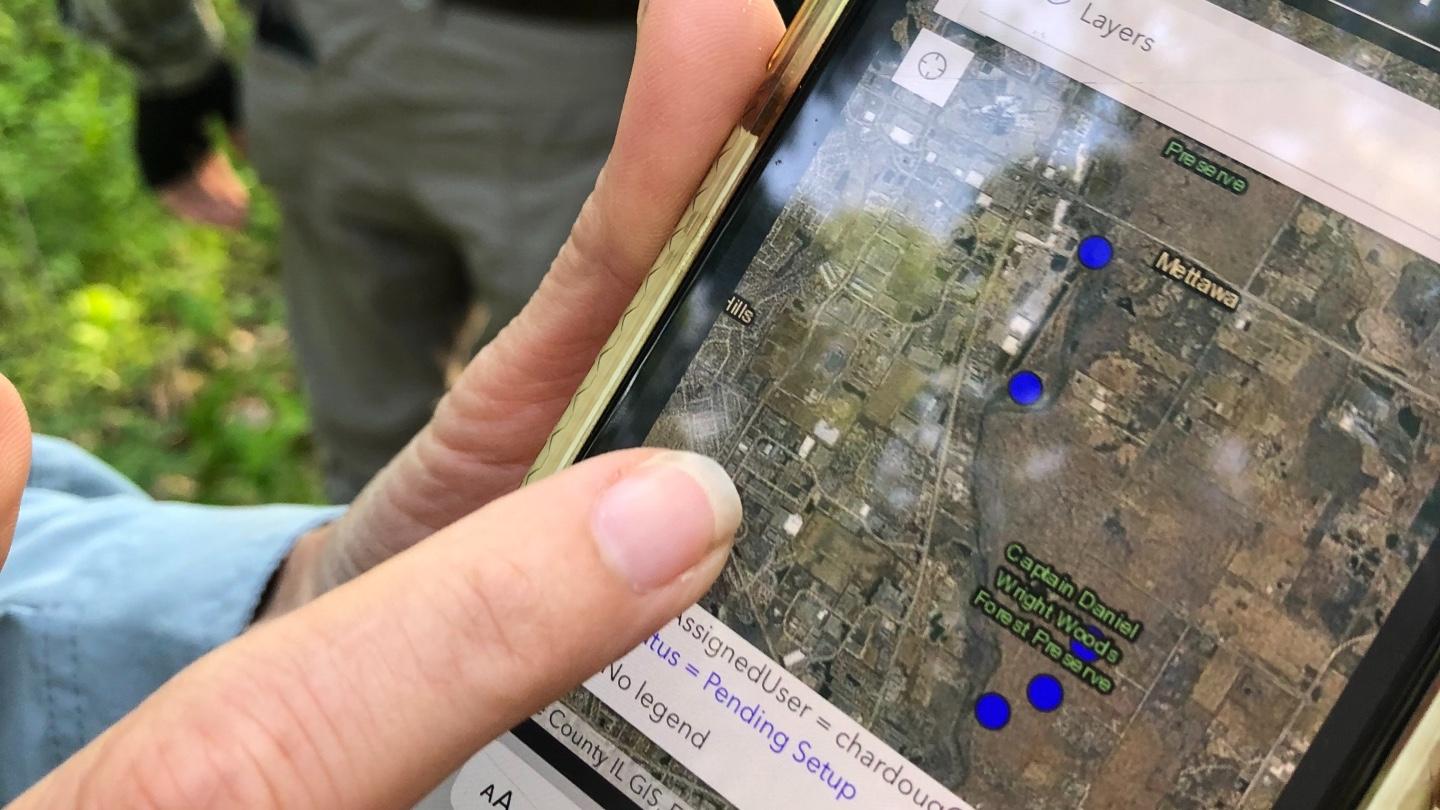

Holding her phone like a compass, Pavelka stepped off the gravel trail, placing her trust in GPS coordinates as she led Reitz through the sun-dappled understory. They were searching for the small flag that marked their destination, and when they spied it, the pair stopped and stood still for 10 minutes.

Reitz cocked his head, listening for birdsong. After a short silence, he heard the distinctive call of a warbler.

“That’s a yellow throat,” he told Pavelka, who entered the information into an app.

Pewee, nuthatch and great crested flycatcher followed, Reitz tossing off the names in Pavelka’s direction without taking his eyes or ears off the trees. Occasionally he lifted his binoculars or camera in the hopes of capturing a closer glimpse of something that flickered into view.

“There’s a second pewee,” Pavelka said, as she tapped the observation into her phone.

A timer signaled the end of the 10 minutes. Pavelka punched in new navigation coordinates and the couple started hiking to their next assigned location, where they would repeat the process.

This simple act of monitoring the presence of breeding birds at specified sites across the Chicago region is how the Bird Conservation Network has, over the course of more than 20 years, methodically amassed a data set that would be the envy of any research institution.

Not bad for a community science project.

AN IDEA HATCHES

Judy Pollock, president of the Chicago Audubon Society, has been along for the ride since the project’s inception.

Back in 1999, 21 conservation organizations teamed up to create a survey of breeding birds, following strict protocols for point counts in June and early July. The parameters were specifically aimed at gathering information related to managed lands — forest preserves, park districts, etc. — in Cook, Lake, McHenry, DuPage, Kane and Will counties.

“That’s been the mission — to tell a story of how birds are doing on managed land,” Pollock said. “The counties control a lot of conservation land. We felt there was a role for us to educate people about how important their lands are. Our primary goal is to make those connections with public land managers.”

The network held a number of meetings with land managers prior to setting up the survey, consulting on monitoring locations and asking for feedback on what type of information would be most useful. Though Pollock said the network works closely with and has solid relationships with land managers, it can be an uneasy partnership at times.

“We’re judging their work, in a way,” she said.

Gary Glowacki, for one, welcomes the input.

“We have 31,000 acres and 8 to 10 ecologists spread very, very thin,” said Glowacki, wildlife biologist at Lake County Forest Preserve District. “Staff alone can’t be the eyes and ears. We need volunteers to fill in the gaps to see if our projects are a success and how species are responding.”

Apart from tabulating the species making their home in region’s parks and preserves, a secondary aim of the survey has been to identify trends — which birds are losing population, which are gaining and which are pushing into new territory.

Among the exciting topline findings in the Bird Conservation Network’s most recent report, released in June: Henslow’s sparrow, a grassland bird losing ground nationally, is thriving in northeastern Illinois, where the sparrow has established a stronghold thanks to the restoration and creation of tallgrass prairie.

“It’s nice to have this proof that our natural areas are so important for these declining birds,” said Pollock. “I knew it, but it was nice to have that confirmed.”

Video: The sights, and mostly sounds, of bird monitoring with Doug Reitz and Charlotte Pavelka in Lake County’s Captain Daniel Wright Woods. (Credit: Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Another bird trending in a positive direction is the red-headed woodpecker. Once dropping precipitously in numbers, the bird appears to be on the rebound in the region.

It’s a comeback Pavelka and Reitz have documented at Wright Woods.

“This was chock-full with buckthorn,” said Reitz, motioning to an area of forest. “They cleared it out and there are so many red-headed woodpeckers now.”

Yet a win for the woodpecker might be coming at the expense of other species.

Similar to Wright Woods, understory was cleared at Miami Woods in Morton Grove, on the North Branch of the Chicago River. “And lo and behold, red-headed woodpeckers returned,” said Pollock. “But I didn’t hear one catbird, and no willow flycatchers. Now it’s time to ask, ‘What other critters are using this land?’”

UNDER PRESSURE

And that’s what makes land management so challenging, said Glowacki.

“Our job is to conserve biodiversity, and sometimes there are competing interests,” he said.

It’s not just a matter of woodpecker vs. catbird, either. It could be snake vs. bird, or salamander vs. dragonfly. “There’s winners and losers, and that’s something we take seriously,” Glowacki said. “How do we decide how to play god — what belongs here and what to priortize?”

It’s a responsibility Glowacki feels acutely, with Lake County home to more threatened and endangered species than anywhere else in Illinois, in part because of its geography. The area is situated at the northern boundary of some species’ range and the southern limit for others.

“A lot of these species are conservation-reliant. Without our help, the species would be gone,” he said. “‘Pressure’ is the right word.”

If habitat weren’t so fragmented, each decision made by land managers wouldn’t be so fraught with life or death consequences, Glowacki said. There would be room and natural resources for all creatures, enough so that if a species found conditions suddenly not to its liking in one forest or prairie, it could shuffle off to a neighboring habitat. Today’s wildlife may have nowhere else to go, which ups the ante whenever a change is made to the landscape.

At Wright Woods, red-headed woodpeckers, which prefer open forests, have benefited from the removal of invasive buckthorn. But the absence of a shrub layer has been detrimental to other species, demonstrating the complexity of habitat management. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

At Wright Woods, red-headed woodpeckers, which prefer open forests, have benefited from the removal of invasive buckthorn. But the absence of a shrub layer has been detrimental to other species, demonstrating the complexity of habitat management. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Bird Conservation Network survey can help land managers determine which species are in need of attention. What it can’t tell them is how to achieve the desired outcome.

For example, the most recent report shows that birds reliant on shrubs for habitat appear to be struggling.

The theory is that while agencies like the Lake County Forest Preserve District have been successfully clearing their forests of invasives such as buckthorn and honeysuckle, they’ve created a void that hasn’t been filled (picture natural areas with “small” and “tall” habitat, but no “medium”). And that’s a problem for shrub-loving wildlife.

Ideally native shrubs and understory trees would be planted in place of the invasives — Glowacki named button bush, ironwood and muscle-wood as candidates — but establishing native shrubs isn’t easy for a numbers of reasons, he said.

Nurseries and other suppliers don’t stock many native shrubs, for starters, he explained, and what they do carry tends to be expensive because there isn’t a whole lot of consumer demand for them.

“Homeowners don’t buy (native shrubs), they buy trees,” Glowacki said.

The forest preserve district has explored contract growing, he said. The obstacle with that solution is it would require grant funding, and grants rarely are offered for the lengthy timeframe it would take to establish a supply of shrubs.

Those are the sorts of complexities ecologists are dealing with as they attempt to restore some semblance of natural order to the region’s forests, prairies and wetlands. It’s a job that never ends.

“When can you sit back and say, ‘We’re done?’” Glowacki asked. “It’s always a continual process.”

Now there’s a new challenge to contend with: climate change.

“We’re just figuring out what is working here and there’s this monkey wrench of climate change,” said Pollock.

Already the breeding bird survey has documented a seeming shift in the range of the acadian flycatcher. It’s a species more commonly found in southern and central Illinois, but Pavelka and Reitz know of one nesting at Wright Woods.

Pollock predicts that in the next 20 years, the survey will record a greater pace of change — winners, losers and range shifts — than it’s charted to date. It’s impossible to say how conservationists will need to adapt current land management practices in response.

“There’s so much we don’t know,” Pollock said. “We’re going to have to take our inadequate knowledge and do the best.”

TECHNOLOGY, BIRDERS' SURPRISING BEST FRIEND

Charlotte Pavelka checks the coordinates of her monitoring sites. Advances in technology have been a big boost to the bird survey, from GPS to apps like eBird. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Charlotte Pavelka checks the coordinates of her monitoring sites. Advances in technology have been a big boost to the bird survey, from GPS to apps like eBird. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Forget the image of a seasoned birder flipping through a field guide to identify an unusual species.

Pavelka and Reitz estimate that 80% to 90% of their observations come from hearing, not seeing. They’ve honed their skills through repeated listenings of birdsong CDs and have gradually gained the ability to name scores of birds just by the patterns of their trills and tweets.

“When you learn bird songs, it changes everything,” Pavelka said.

Today it’s all about apps like eBird and Merlin, which immediately narrow search results from “every bird in the world” to “likely birds at your location.” Some of the latest technology even allows birders to hold up their phone and the app will distinguish bird species from ambient sounds.

These advances have significantly lowered the barrier for newcomers to join the Bird Conservation Network’s volunteer corps.

“It expands the pool of who can monitor,” said Pollock, who noted that it takes roughly 250 people to collect data from the survey’s 2,700 monitoring points. They range in age from early 20s to late 80s.

Indeed, it’s technology that’s enabled the survey to exist at all, she said.

When the project first began in 1999, it was the early days of the Internet. The Field Museum set up an online interface for monitors to input data, but the museum couldn’t sustain the survey in the long term.

“There’s just no money for monitoring,” Pollock said.

The Field handed off the project to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, where the survey ultimately led to the creation of eBird in 2002, said Pollock.

“It was the same thing with GPS,” she said. “Whatever the early GPS was, we were using it.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]