Prairies are characterized by grasses and wildflowers, as well as their unique soil composition. (Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie / U.S. Forest Service)

Prairies are characterized by grasses and wildflowers, as well as their unique soil composition. (Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie / U.S. Forest Service)

Almost as soon as it was dubbed the Prairie State, Illinois began to lose the very features that inspired the nickname.

In short order, millions of acres of prairie that had gone undisturbed since the retreat of the last glaciers were transformed into some of the most productive farmland in the U.S. or churned to make room for cities and ultimately suburban sprawl. In the process, prairie, which once covered 60% of Illinois was all but erased.

What’s left is measured in decimal points. Among conservationists’ most oft-cited stats, only .01 of 1% of high-quality original prairie remains. Indeed, so little prairie still exists in Illinois, most residents of the state have never encountered this rare landscape.

“I don’t think people have a chance to see and understand prairies,” said Kelly Mikenas, assistant professor of biology and director of the environmental studies program at Elmhurst University. “There aren’t that many opportunities to go and visit prairies.”

Whereas the word forest immediately conjures up specific images — people know what trees look like — prairie draws a blank or, worse, the brain serves up uninformed guesses, like faulty search engine results or autocorrect failures.

Unmowed field? Not a prairie.

Rural America? Not a prairie.

Garden plot filled with native plants? Not a prairie.

Swaths of roadside weeds? Not a prairie.

The mistaken association with weeds has been perhaps the most damaging to prairie’s reputation, and is the impetus behind a movement to reference prairie plants by their Latin names instead of common names: Vernonia gigantea, for example, flat out sounds more desirable than giant ironweed.

A lack of familiarity with or connection to prairies has made what’s left of them vulnerable to development. Without a charismatic species to rally around, prairies tend to disappear with little notice. There are no sequoias to stir public sentiment. No dramatic waterfalls, no awe-inspiring cliffs, canyons or snow-capped peaks. No polar bears.

Today, having flown not so much under the conservation radar as completely off it, prairie is one of the most endangered habitats on the planet, according to experts.

To know prairies is to love them, Mikenas said. So here, then, is an introduction.

What is a prairie?

Big bluestem grass creates a colorful burgundy ribbon in a prairie. (Laura Hubers / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Big bluestem grass creates a colorful burgundy ribbon in a prairie. (Laura Hubers / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

A prairie, by another name, is a grassland. Its primary characteristic, as the name implies, is the presence of native prairie grasses.

Not to be confused with the stuff of lawns, prairie grasses go by names like side-oats grama, prairie dropseed and Canada wild rye. Apart from their much greater height, prairie grasses differ from turf varieties in that they tend to grow in bunches (called clump-forming) rather than spreading like sod. Whiskery plumage, unusual seed heads and striking colors are other prairie grass hallmarks.

Big bluestem, the official state prairie grass of Illinois, is among the most dominant. It can grow taller than an NBA center, glows burgundy in fall and terminates in spikes that look like a turkey foot.

But grasses are only part of a prairie’s story. Wildflowers are another (technically: flowering plants, called forbs, typically of a non-woody nature), with hundreds of species ranging from familiar coneflowers to rarities like the prairie fringed orchid. Trees occasionally make a cameo, but their notable absence is another prairie calling card. Traditionally, dry conditions, fire and species such as elk kept trees from establishing in prairies.

Though Illinois prairie no longer supports elk, it does provide food and shelter to a host of wildlife, from the tiniest of insects to small herds of reintroduced bison.

This interconnected web of grasses, forbs, wildlife and microorganisms is literally grounded in prairie soil, a complex stew that’s perhaps the most critical and yet least understood component of what makes a prairie a prairie.

“It’s really the foundation, and yet we know so little about it,” Mikenas said. “We’ve done a lot of studying of soil cores and we can extract DNA, but that science only goes so far. We only have the ability to identify a few species of bacteria and fungi, and there are tens of thousands of bacteria in a gram of soil.”

Trying to replicate an individual prairie’s soil is almost impossible, she said. It’s not just about calculating the exact amount of certain minerals, or the ratios of sand, silt and clay, but unknowable details like the number of air pockets.

“It’s like trying to bake a cake, but you don’t know the ingredients or the proportions,” said Mikenas.

Purple prairie clover. (Jennifer Jewett / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Purple prairie clover. (Jennifer Jewett / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The most iconic type of prairie — and yes, there’s more than one kind — is tallgrass, said Mikenas. Picture covered wagons rolling through wheel-high grasses, she said. That’s tallgrass prairie.

The soil is usually very deep and so are the roots of tallgrass plants, creating a world below ground as rich and diverse as above, and sequestering carbon as the roots extend down into the earth.

And then there’s the color. Grassland may imply an unbroken sea of green, but prairies are rainbow-hued. From spring through fall, prairie flowers bloom in a riot of purples, pinks, yellows, oranges and whites, basking in the full sun that beats down on this almost treeless environment.

All that sun means tallgrass prairies are hot. There’s no shade and very little water, Mikenas said, and the irony is that prairies are often at their most beautiful when conditions are the most brutal for visitors.

“They’re inhospitable ... to us,” but that’s part of what makes them so remarkable, she said. “These scrappy plants can live in these places that might be discouraging, bringing immense beauty to inhospitable areas.”

Apart from tallgrass, there’s mixed and shortgrass prairie, differing in soil moisture, glacial history, topography (spoiler alert — not all prairie land is flat) and soil composition. There are sand prairies, gravel prairies and even dolomite prairies, where the soil is so shallow, bedrock is exposed in places.

That same bedrock, gravel or sand frustrated farmers’ attempts at cultivation and is one reason any prairie remnants can still be found in Illinois.

What is a remnant prairie?

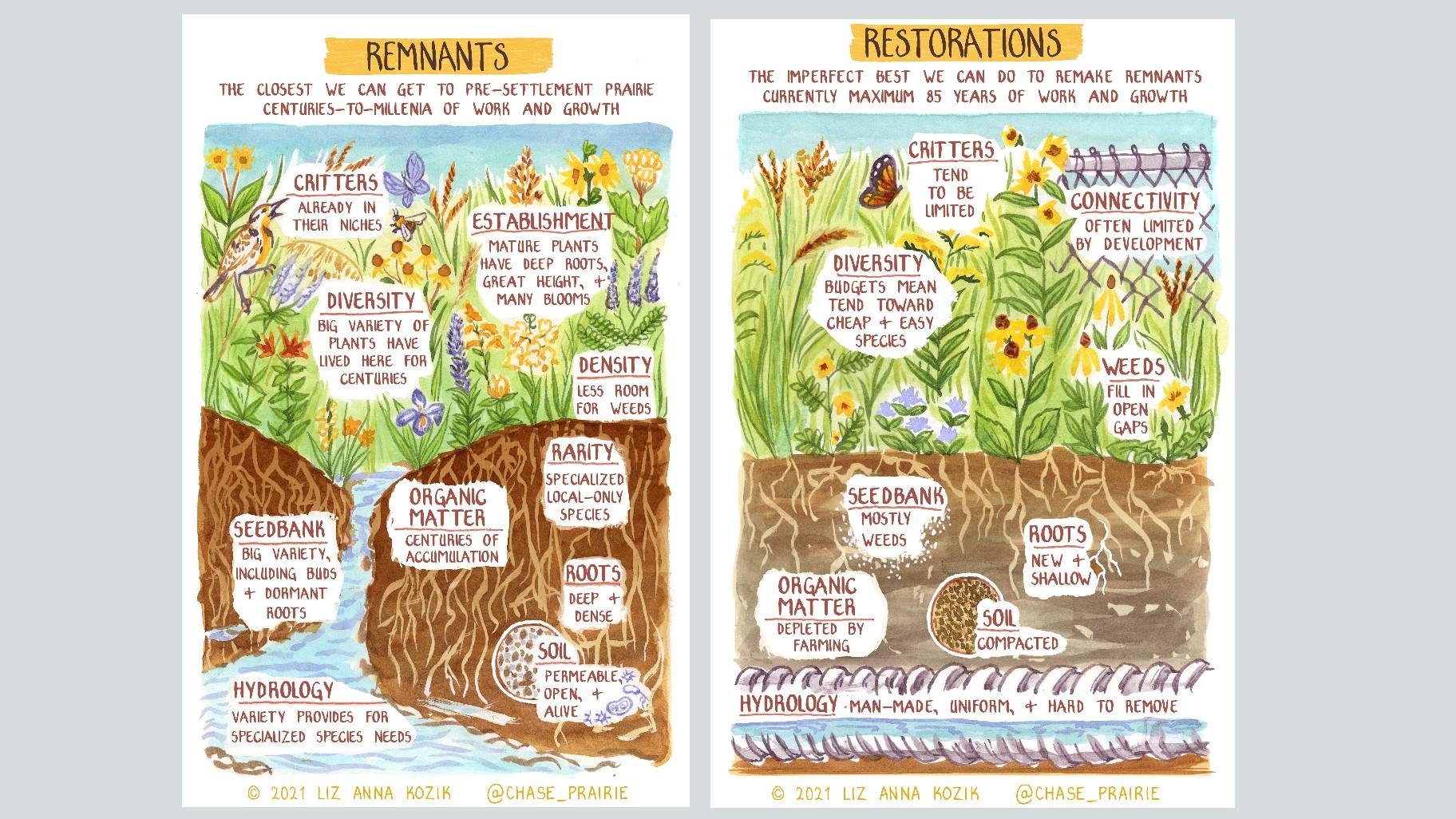

Environmental studies scholar Liz Anna Kozik creates comics that depict and explain the history of prairies and their restoration. Here she illustrates the differences between prairie remnants and restoration. (Courtesy of Liz Anna Kozik)

Environmental studies scholar Liz Anna Kozik creates comics that depict and explain the history of prairies and their restoration. Here she illustrates the differences between prairie remnants and restoration. (Courtesy of Liz Anna Kozik)

One definition of a remnant is that it’s never been plowed, said Becky Barak, a conservation scientist at the Chicago Botanic Garden and an adjunct professor in Northwestern University’s plant biology and conservation program. Once land has been plowed, “everything in the soil that marked it as prairie is gone,” she said.

There are some 2,000 acres of remnant prairie in Illinois, which is as close as we can get to the state’s ancient post-glacial landscape. But to think of remnants as pristine prairie is a bit of a mischaracterization.

Not even remnants have escaped the influence of human activity, including exposure to light pollution, air pollution and herbicides applied to adjacent properties, according to Mikenas. There’s also no getting around the isolated, patchwork nature of remnants compared with what was once an unbroken vista as far as they eye could see.

All remnants have undergone some level of change, Barak said, but the degree of that disturbance varies widely. There are high-quality remnants, the rarest of the rare, which are as intact as a landscape can be considering centuries of proximity to agricultural or urban development. Other sites are so degraded, they’re scarcely recognizable as prairie. Still with care and management they can be brought back from the brink.

What all remnants have in common, regardless of quality, is that the key elements of original prairie, an ecological memory, are still present: seeds, roots and soil that have evolved together over thousands of years.

How is it possible, people might wonder, to know whether a remnant has never been plowed, grazed or otherwise tampered with? Land use records only go back centuries, not millennia.

In some cases, paleoecological studies have been conducted, Barak said, showing evidence of prairie plants dating back 10,000 years.

A far more analog method is the hands-on evaluation of a site. Scientists look for certain markers, Barak said, such as the really deep plant roots characteristic of a remnant. They’ll also catalog species, with biodiversity distinguishing a bona fide prairie remnant from a wannabe. Remnants will contain hundreds of different species in even a small section versus mere dozens in areas that have been altered.

Other indicators include the presence of rare species.

“Flora of the Chicago Region” is a 1,300-page plant book scientists like Barak and Mikenas use to assess a site. “We know there are some species only found in remnants. They need this intact environment,” Mikenas said.

Those are the species most at risk of going extinct if remnants are lost, and often the most difficult to successfully establish in a prairie restoration project.

What is a prairie restoration?

Restoration work can involve reintroducing native species to a landscape being reclaimed from agricultural, industrial, residential or commercial use. (Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service)

Restoration work can involve reintroducing native species to a landscape being reclaimed from agricultural, industrial, residential or commercial use. (Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service)

In some cases, restoration refers to rehabilitating a remnant, one that may have become overgrown with invasive species, for example.

In those instances, “restoration can be an exercise in removal” by peeling back layers, said Barak, and reintroducing natives.

More typical are situations where agricultural, industrial, residential or commercial acreage is reclaimed as a natural area, such as a farmer donating or selling their property to a land trust. Another example could be the demolition of a factory, where the site is topped off with soil and prepped for native plants, slated to become a preserve.

In these scenarios, prairie restoration is akin to historical recreation — the equivalent of presenting a reasonable facsimile of the cabin Abe Lincoln grew up in because the original no longer exists.

This sort of restoration isn’t prairie in the same sense as a remnant, most notably because restored prairies are engineered by human hand. “They’re created by us,” Mikenas said. “And there’s so much about these habitats we don’t know. Restoration is a scientifically informed field, but we’re only doing the best we can with what we have.”

In a way, restoration specialists are aiming to unlock the key to nature’s secret sauce recipe. And there’s been a lot of trial and error.

“People talk a lot about the ratio of grasses to forbs,” Barak said, as an example. Early restoration projects would typically include big bluestem — the granddaddy of prairie grasses — in their planting schemes. But big bluestem doesn’t behave the same way in a young restoration as it does in an established remnant, displaying a tendency to overwhelm forbs. Today, big bluestem is planted sparingly, if at all, she said.

Perhaps one of the biggest constraints facing restoration ecologists, Barak said, is the availability of seeds for prairie plants (not cultivars or even nativars). These need to be collected from remnant prairies, where some plants are so rare and few in number, it’s not possible to gather enough seed to sow elsewhere. Seeds of spring blooming species are also harder to collect, Barak said, and cost is another factor.

As scrappy as prairie plants are, they can also be finicky. Some have proven downright obstinate, refusing to germinate in greenhouses or at restoration sites.

Among restoration’s “white whales” are plants called hemiparasites — they’re capable of photosynthesis but they obtain water and other nutrients from a host plant. Bastard toadflax is an example of a hemiparasitic prairie plant that’s yet to take hold in restorations, according to Barak, but not for lack of trying.

In some cases, hemiparasites can help keep dominant plants under control, Barak said. That and any other benefits they provide — benefits scientists, perhaps, have yet to uncover — are among the missing puzzle pieces in any restoration.

Given all of the aforementioned constraints, prairie restoration projects tend to rely on a short list of plants that are the easiest to establish and most adaptable to non-prairie soil — think of them as restoration’s greatest hits — resulting in far less diversity than would be found at a remnant, not just in terms of flora but also the fauna.

Think of the relationship between milkweed and the monarch butterfly — without the former, the latter disappears. “That kind of close relationship between species exists many times over in a prairie,” Mikenas said.

Milkweed seed scattering at a Chicago Park District natural area. Prairie remnants and restoration projects go hand in hand in preserving biodiversity. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Milkweed seed scattering at a Chicago Park District natural area. Prairie remnants and restoration projects go hand in hand in preserving biodiversity. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Gradually a restoration’s soil and processes will come to resemble a prairie, but the emphasis is on gradual, said Barak. Progress is measured not in years but over the course of multiple generations of human lifespans.

The suggestion that a prairie can be translocated — uprooted from a site where it’s existed for thousands of years and plunked down on a plot of land elsewhere — manages to both vastly overestimate what restoration can accomplish and vastly underestimate the complexity of a prairie ecosystem, according to experts.

“Even if you dug down 10 feet and could scrape up and move a prairie, you’re not going to have the micro-topology,” said Mikenas. “There are all of these tiny differences. It matters and it does have influences.”

Restoration isn’t a substitute for remnants but rather the two go hand in hand, according Mikenas. Creating new habitat is as vital as holding onto existing ecosystems, making restoration one of the most important tools in a conservationist’s toolbox, she said.

The great and critical challenge of our time is the preservation of biodiversity in support of a healthy, functioning planet, Mikenas said.

“You may say, ‘This one little habitat doesn’t matter.’ But they all add up,” Mikenas said. “That’s what led us to this situation now, where we have this patchwork.”

The question for humans weigh is whether we can live without prairie. And if we can, do we want to?

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]