Bell Bowl Prairie, a high-quality remnant of Illinois prairie, located within the boundary of Chicago Rockford International Airport. (Courtesy of Cassi Saari)

Bell Bowl Prairie, a high-quality remnant of Illinois prairie, located within the boundary of Chicago Rockford International Airport. (Courtesy of Cassi Saari)

Conservationists are in a race against the clock to save a five-acre patch of rare Illinois prairie from being bulldozed as part of a 280-acre expansion of the Chicago Rockford International Airport’s cargo operation.

Environmentalists have until Nov. 1 to convince either the airport’s board of commissioners or Illinois elected officials to tweak the site plan for the cargo facility in order to spare the prairie, which has gone undeveloped for thousands of years.

“It’s really overwhelming, having your feet on something that’s never been developed,” said Jennifer Kuroda, president of the Sinnissippi Audubon chapter. “It’s the original land of the state.”

The outcome doesn’t have to be an “either-or” — either jobs and economic development or protecting a vestige of the Prairie State’s namesake landscape — it can be “both-and,” said Kerry Leigh, executive director of the Natural Land Institute, which is leading the conservation charge.

“We are not against economic expansion,” said Leigh. “There’s a win-win here, but only if they engage with us. We’re trying to get the airport to hear us and respond. We want to have a conversation but they have shut us down.”

Airport officials declined, through a spokeswoman, to comment on or be interviewed for this article.

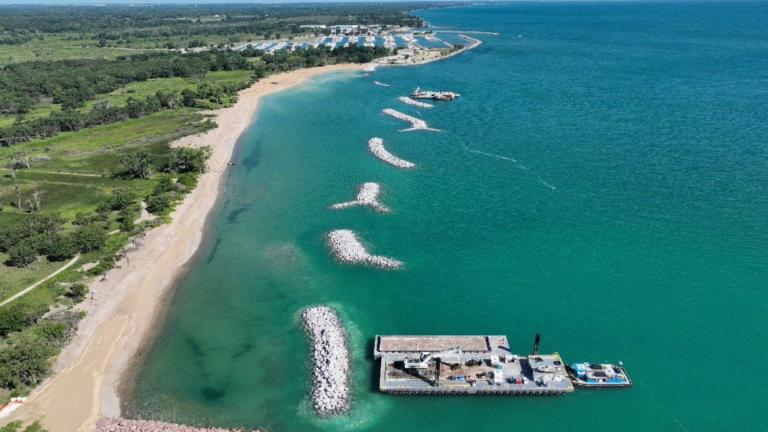

Satellite view of Chicago Rockford International Airport, with prairie area marked. (Google)

Satellite view of Chicago Rockford International Airport, with prairie area marked. (Google)

Bell Bowl Prairie is part of the airport’s nearly 3,000-acre property, but it predates the airport by several millennia, carved by the retreat of the last glaciers.

The bowl’s steep, dry, gravelly slope kept it from being farmed or grazed, leaving its community of plants and wildlife intact.

Humans eventually figured out a use for the prairie: From 1917 to 1946, the land was home to Camp Grant, a U.S. Army training base and prisoner of war camp during World War I and World War II. Then in 1946, Camp Grant was pressed into a different kind of service when the state of Illinois created the Greater Rockford Airport Authority, according to the airport’s own history published online. (This history formerly referenced Bell Bowl Prairie but has lately been scrubbed of all mentions of the natural area.)

The prairie nearly didn’t survive the airport’s construction. Back then, it was George Fell who quite literally faced down earth moving equipment, ultimately convincing officials of Bell Bowl’s value and striking up a management agreement. Fell would go on to establish the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission and to found the Natural Land Institute, which has remained involved with Bell Bowl’s stewardship in partnership with entities such as the Forest Preserves of Winnebago County.

“Our last work day there was in July and no one said a word” about the expansion plan, said Leigh.

The endangered rusty patched bumble bee. (Courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The endangered rusty patched bumble bee. (Courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Birders love Bell Bowl Prairie. Its status as a high-quality natural community means it’s teeming with habitat and food for a diverse range of migratory species, including the secretive black-billed cuckoo.

It was a birder who raised the alarm about a potential threat to Bell Bowl, having spotted construction vehicles near the prairie in August.

That’s when Leigh became aware of the airport’s planned cargo expansion, which had been cleared for takeoff, so to speak, in 2018.

How did the airport’s designs on the prairie escape the attention of its stewards for so long?

Leigh blames a breakdown in communication between Natural Land Institute and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, whose staff, she said, was gutted during the administration of former Gov. Bruce Rauner.

“Normally what happens with any kind of construction or development like this, there’s a consultation process that goes through IDNR,” she explained. “According to DNR, they did the process correctly.”

But no one involved with any local conservation or environmental organization recalls receiving information about the airport’s proposal or notification of a public meeting that DNR said it held, Leigh said.

If people like Leigh and Kuroda had been in attendance at the meeting, they would have been apprised of the results of an environmental assessment in which a field investigation, conducted on a single August day in 2018, turned up no endangered species on the site of what’s been dubbed the Midfield Air Cargo Development. (The assessment describes the site as “primarily agricultural land, open fallow fields, airfield infrastructure and a remnant prairie area, referred to as the Bell Bowl Prairie.”)

Investigators were looking for species like the state-listed endangered large-flowered penstemon and federally endangered or threatened rusty patched bumble bee, prairie bush clover and eastern prairie fringed orchid. According to the assessment: “IDOT (Illinois Department of Transportation) cross-referenced the preferred habitat of each of the listed species with knowledge of the project area and determined that the listed species are not present.”

Critics have pointed out several flaws in the field study, not the least of which being its reliance on a lone day of observation. On Aug. 8, 2021, the rusty patched bumble bee was seen at Bell Bowl and conservationists confirmed, via uploads to iNaturalist, that large-flowered penstemon (which blooms not in August but in late spring or early summer) was spotted by multiple visitors to the prairie in 2021.

The presence of the rusty patched bumble bee, in particular, brought expansion work at the airport to a halt, at least in the Bell Bowl vicinity.

IDNR recommended “any work related to construction that disturbs the ground or may remove flowering plants be done between Nov. 1 and April 1 to prevent impacts to foraging (rusty patched) bees,” a department spokesperson told WTTW News. (Though the rusty patched bumble bee is protected, its habitat isn’t, a loophole that’s the subject of an ongoing lawsuit.)

The department has further recommended “impacts to the site be avoided to the extent practicable. If impacts cannot be avoided, the IDNR requested the opportunity to collect seeds and translocate plants and prairie materials to a department-approved site,” the spokesperson said. “The IDNR is working with the airport regarding that request.”

Leigh called the option of translocation “a complete failure.”

“That’s not this place that’s existed for 8,000 to 9,000 years. It’s like scraping a few skin cells and saying, ‘We’re going to recreate this person,’” she said. “If DNR thinks that’s saving the prairie, I’m deeply disappointed.”

In September, John “Jack” White drove 183 miles from Urbana to Rockford to attend a meeting of the airport’s board.

White is the botanist George Fell hired out of college to work for the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission. In the 1970s he led the Illinois Natural Areas Inventory, a comprehensive survey of the state’s high-quality prairies, wetlands, forests, savannahs and other natural areas. Bell Bowl Prairie was identified as “outstanding” by the inventory.

In a lengthy statement, White made an impassioned plea for Bell Bowl’s survival — in place, as-is — calling parts of it “pristine and primeval” and argued against the translocation alternative.

“Transplanting any part of Bell Bowl Prairie would be an exercise in futility, not a viable option,” White said. “It would be taking the living equivalent of the most intricate, exquisite stained glass church window, shattering it, casting the shards on the ground and then hoping that it will reassemble itself.”

The prairie is so much more than just a collection of plants, he said. It’s the birds, animals, insects, fungi and microorganisms that all exist in an interrelated web. They can’t be separated from one another and still be considered Bell Bowl Prairie, White said.

‘What We’re Going To Lose’

Cargo is king at the Rockford airport, which ranks among the top 20 in the nation for the movement of goods.

Even during the pandemic, when passenger service plummeted, Rockford still experienced growth in its cargo traffic, fueled in large part by e-commerce. For 2020, airport officials reported the “largest year-to-date landed cargo weight in the organization’s history,” totaling 2.7 billion pounds, up 15% percent over 2019.

Amazon is an easy target for conservationists to pin the blame on for the potential loss of Bell Bowl and they’ve been hashtagging the company’s founder Jeff Bezos on social media as part of their grassroots campaign to save the prairie. But the boom in Rockford’s cargo business, which the airport has strategically been building toward for years, is bigger than any one company or person.

Along with an Amazon Regional Gateway, Rockford operates the second-largest North American hub for UPS, and also serves air cargo carriers from and destinations in Germany, Belgium, India, China, South Korea and more.

“We have been working very hard over the last several years to bring in what we call heavy freighters from all over the world,” Mike Dunn, the airport’s executive director told an airline industry publication in 2020 as he touted the planned cargo expansion.

Illinois Sens. Dick Durbin and Tammy Duckworth have helped funnel tens of millions of federal dollars toward the airport, including funding in 2021 allocated for expansion of the cargo apron.

Against this backdrop, the bid to save Bell Bowl would appear to be an uphill battle. Supporters of the prairie are planning rallies, investigating legal options, bombarding Gov. J.B. Pritzker with emails and trying to get people to care about a piece of land that even its fans admit could easily be mistaken for weeds.

Where mountains will make a person’s jaw drop, prairies are an acquired taste and only reveal their wonders and charms on close inspection. Even then a person needs to know what they’re looking at.

For Jennifer Kuroda, who’s been birding at Bell Bowl for years, it took a visit to the prairie with John White and seeing it through his eyes to truly appreciate its beauty.

“Before, I just knew it as a good birding location,” she said. “I just learned so much from Jack. The way he talked about the plants, I got choked up. You get a sense of what we’re going to lose.”

Test of Political Will

“Humans are always trying to turn prairie into something else — cropland, houses — and almost always those alternatives win out,” said Don Miller, a longtime steward of Rockford’s Severson Dells Nature Center, who spoke at a recent meeting of Bell Bowl advocates.

The North American prairie is one of the most endangered ecosystems on earth and continues to lose ground. If there’s one card for conservationists to play with officials, the rarity one is it.

In August, Gov. Pritzker signed the Illinois Thirty-by-Thirty Conservation Task Force Act, which authorizes the formation of a task force designed to determine ways the state can protect 30% of its land and water resources by 2030.

The act states: “Rapid land development in Illinois has led to the loss of historical and archaeological sites that embody the heritage of the state ... In order to support national efforts and provide state leadership to address the deterioration of natural systems, loss of biodiversity, and rapid land development, Illinois must establish a bold goal for the amount of land to be protected by the year 2030.”

Conservationists say Bell Bowl Prairie offers a test of whether “30 by 30” is just a catch phrase or whether there will be action beyond the rhetoric, especially when the going is rough.

If one of the few remaining high-quality prairie remnants in the Prairie State doesn’t embody the heritage of the state and merit protection, they ask, what does?

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]