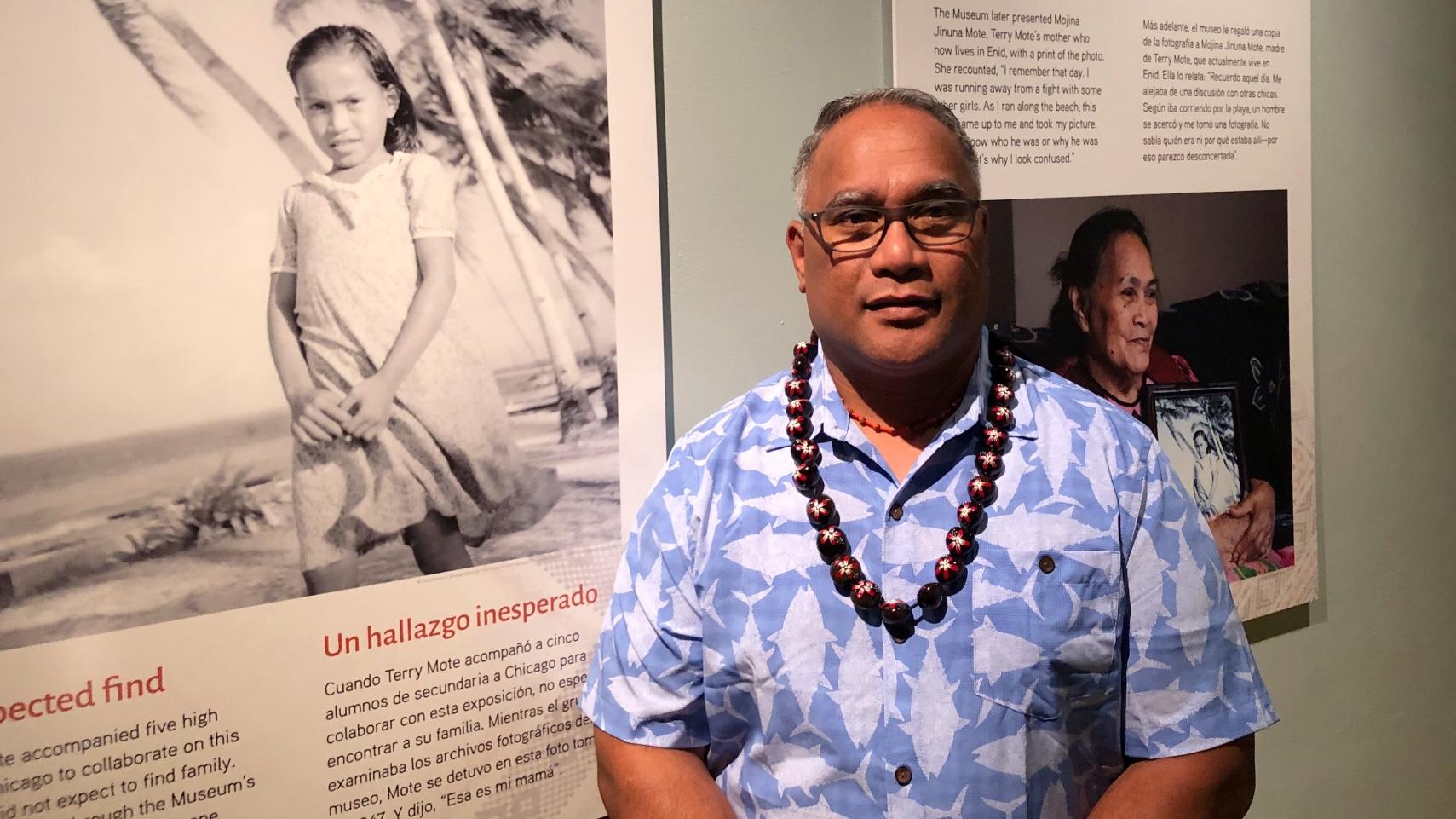

Terry Mote, straddling past and present, as he visits the Field Museum’s exhibit on the Marshall Islands. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Terry Mote, straddling past and present, as he visits the Field Museum’s exhibit on the Marshall Islands. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Two years ago, Terry Mote traveled from his home in Enid, Oklahoma, to the Field Museum as part of a contingent of Marshall Island expatriates tapped to assist curators in developing a new exhibit about their homeland.

As Mote combed through the Field’s collection of artifacts related to the Pacific Island nation, he came across a photo of an unidentified schoolgirl dating back to the 1940s. The child in the short-sleeved dress, who’d managed a tentative smile as she looked into the camera of a visiting Field anthropologist, would be an elderly woman now, but Mote recognized her instantly.

“That’s my mom,” Mote said. “My younger sister looks just like her.”

Ryan Schuessler, an exhibition developer at the Field, would later travel to Enid to surprise a tearful Mojina Jinuna Mote with a copy of the image, which she recalled posing for but had never seen. A photo of Mote in the present day, clutching the picture of her younger self, was incorporated into the Field’s display, alongside the original from 1947.

The narrative came full circle this June, when Terry Mote and the rest of the 2019 group from Oklahoma returned to the Field to view the exhibit they had helped shape. He stood between the two images of his mother, straddling past and present, with the once-unnamed child no longer anonymous. “My mom’s story was like a book closed for so many years,” Mote said. “Now we can open the book and flip the pages.”

It was a powerful moment for Mote, and one that he hopes to share with his mother and 13 siblings. “I’m planning on bringing my brothers and sisters. We want to do it on Mom’s birthday, Feb. 14,” he said. “One day, mom will be gone, but her spirit will be here. Everything in this room, everyone will feel connected.”

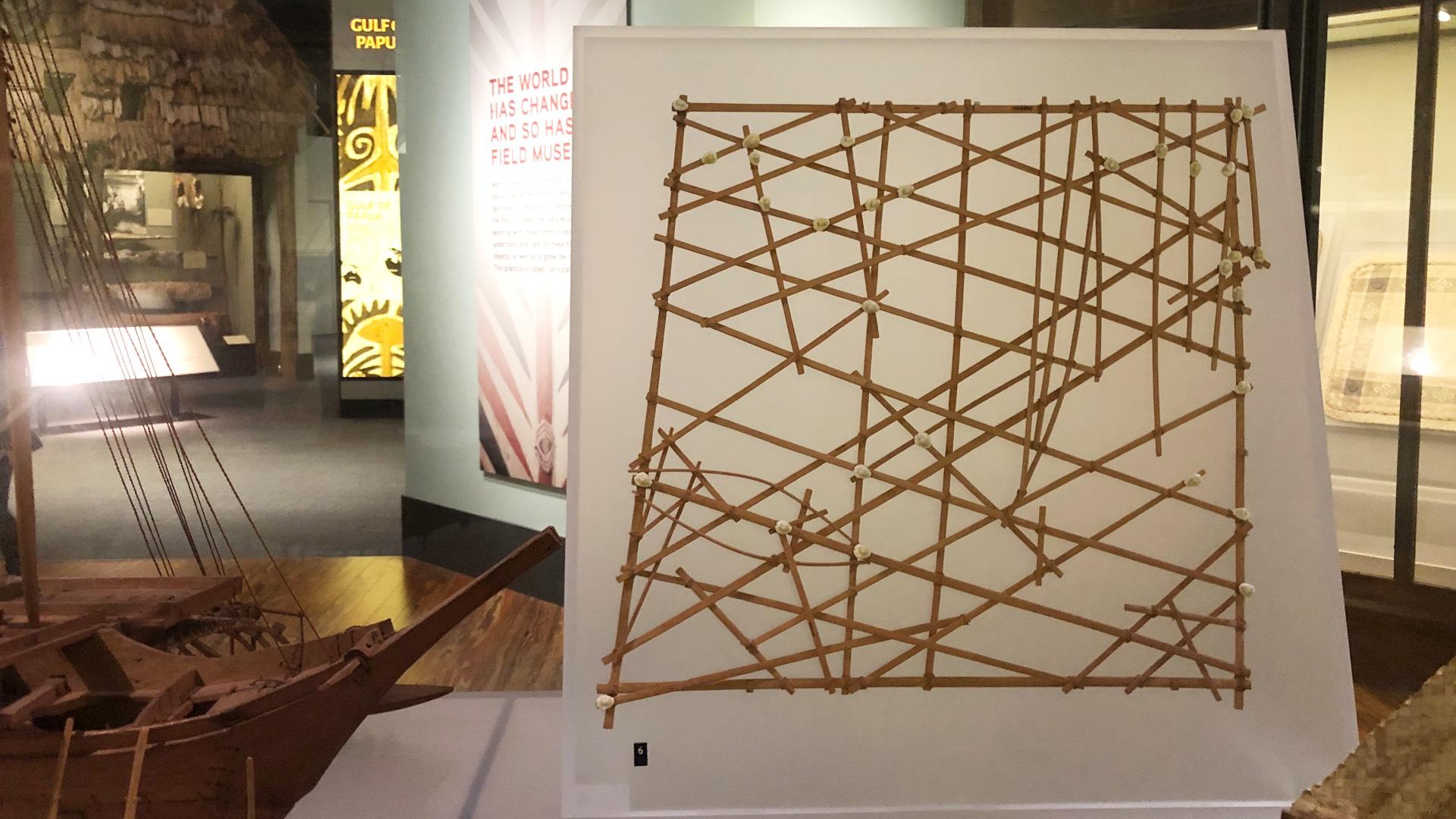

The Marshallese are masterful navigators, using stick charts to map the nation’s islands and ocean currents. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Marshallese are masterful navigators, using stick charts to map the nation’s islands and ocean currents. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field’s Regenstein Halls of the Pacific explore the culture and history of the Pacific Islands, which include New Guinea, New Zealand, Hawaii, the Marshall Islands and the Philippines, among others.

Many of the objects on display — representing a small fraction of the museum’s holdings — date to the 1890s or early 1900s and were collected decades ago. In the past, the Field would have taken a top-down approach to mounting an exhibit in the halls, determining with institutional authority which objects to place on view, how to characterize them and what to say about the people to whom they once belonged.

Misrepresentation was common.

Leilani Lee, executive director of the Aloha Center Chicago, remembered once seeing a display of tikis at the Field all grouped in a single case, despite being from different cultures, nuanced differences lost in the jumble. “Where are the stakeholders?” Lee pointedly asked the Field.

She credits John Terrell, Regenstein curator, with promoting the practice of co-curation, in which Field staff collaborate on displays with the people whose culture is being showcased. Today, the entrance to the Regenstein Halls has been designated a co-curation gallery, and that’s where the Marshall Islands exhibit can be found.

Lee served as a liaison on the project. “I’m happy I’ve been here long enough to see great progress,” she said.

Centering native peoples in the telling of their own story represents a marked departure within the field of anthropology, which long discounted the knowledge and voices of non-Westerners.

There’s a sense now of “you don’t talk about us without us,” said Schuessler. “The Marshallese have the perspective, they should be the ones to present their culture.”

For the Marshall Island exhibit, the community group — the Enid Micronesian Coalition — chose the themes and the items to be shown. Field staff spent time in Enid and also went to the islands themselves to gain a better understanding of the objects in its collection — how they’re used and in what context — as well as to study contemporary Marshallese life.

“We try to get as holistic a view as possible, to fill in gaps, to see what we might be missing,” said Monisa Ahmed, exhibition developer. “You’re talking about people’s culture, these objects hold spiritual weight. It’s important to learn from the people on the islands, and to see how these traditions keep going.”

Evencilla Malolo was among the students from Enid, Okla., who collaborated with the Field Museum on the Marshall Island exhibit. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Evencilla Malolo was among the students from Enid, Okla., who collaborated with the Field Museum on the Marshall Island exhibit. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Teenager Evencilla Malolo was among the Enid delegation of Marshallese that consulted on the Field exhibit.

“It was very surreal,” said the high schooler. “I didn’t think they’d ask my opinion.”

As a group, the Marshallese agreed they wanted to highlight items that typically would be found in a home every day, chief among them the jaki, a hand-woven floor mat no historical or contemporary Marshallese household would be without.

For Malolo, who was born in the U.S., the jaki is a tangible tie to a homeland she may never see. Though her mother was born and raised in the Marshall Islands, the family came to the states long ago in search of jobs, better education and access to health care.

“My mom misses it. It was their home,” Malolo said. “I feel sad I didn’t get to experience it.”

Working on the exhibit was a way for the teen to bridge that divide and gain an understanding of her roots. How she and other Marshallese who’ve been assimilated into American culture will keep that spirit alive with successive generations is a question mark. “I’m still figuring it out myself,” said Malolo.

In some ways, the exhibit at the Field is as much for Marshallese like Malolo as it is for the general museum audience, said Mote, who grew up on the islands and moved to the U.S. in 2007.

“The younger generation, they don’t have the connection to our culture. Every time I speak English with them, I feel guilty. The kids are forgetting how to speak Marshallese,” he said. “When they walk through this display, they feel like they belong, they share in who we are. The artifacts, the handicrafts, they are the DNA of the ancestors.”

KNOWLEDGE IS EVER CHANGING

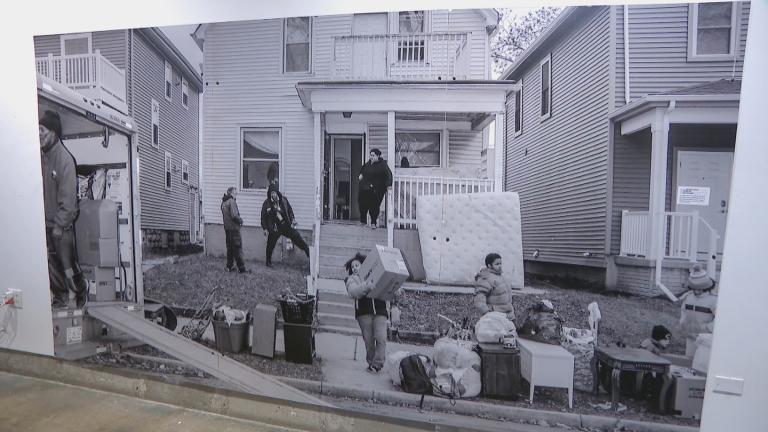

The Field Museum reworked its treatment of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands based on feedback from the Marshallese. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum reworked its treatment of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands based on feedback from the Marshallese. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Marshall Islands, situated roughly halfway between Hawaii and Australia, is an island nation spread across 29 coral atolls comprising nearly 1,200 low-lying islands and islets. It has a population of approximately 60,000 people, with another 30,000 Marshallese living in the U.S. where they hold a unique status — neither immigrants, refugees nor citizens, but allowed to live, work and study in the States without a visa. (Some 3,000 Marshallese live in Enid. The largest community is found in Arkansas.)

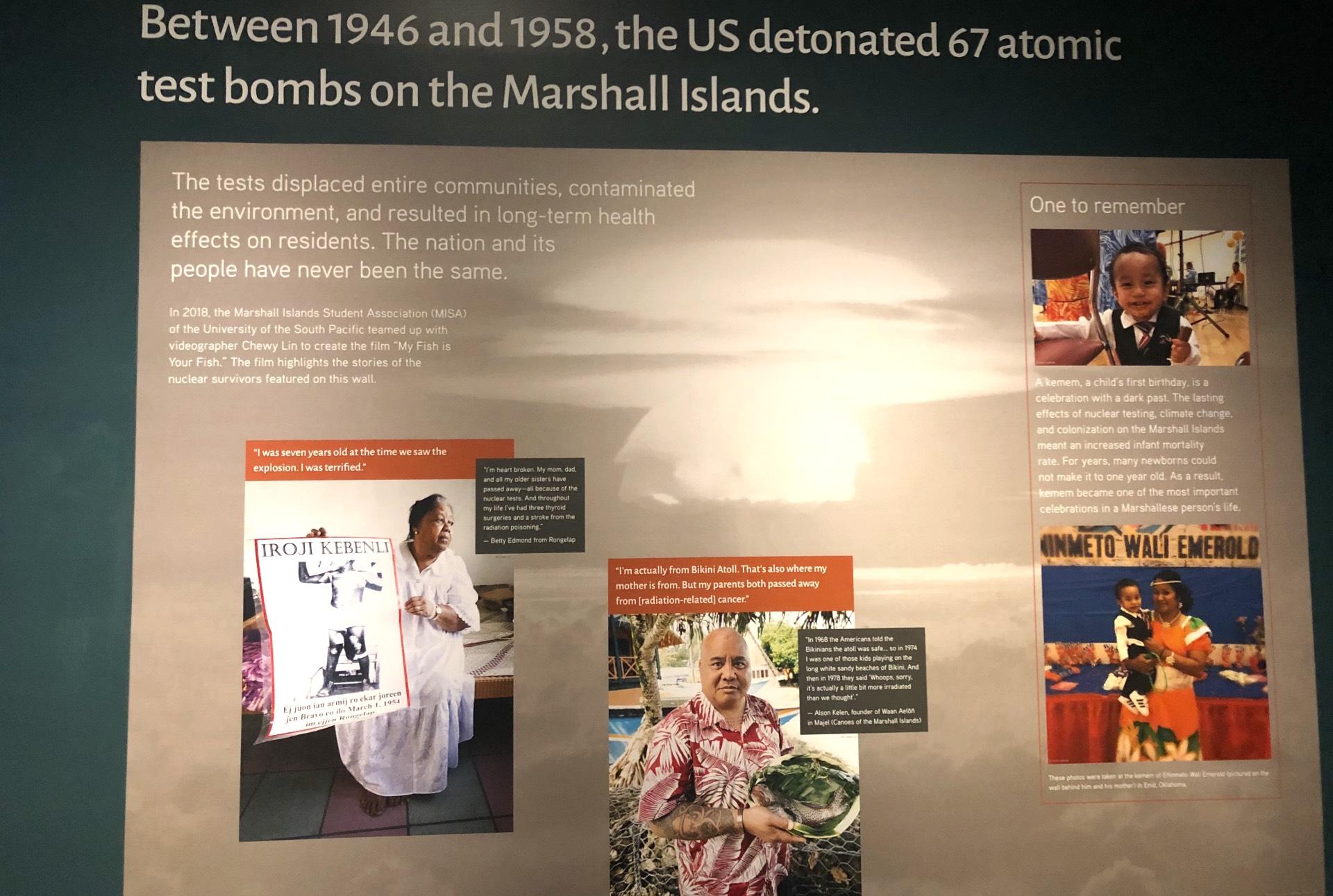

Colonization, nuclear testing and now climate change have all taken their toll on the Marshallese, points the Enid coalition wanted the Field Museum to revisit in its permanent Halls of the Pacific exhibits.

Students were asked to walk through the halls and make note of what they liked and what they didn’t, and returned with one page of positive comments and six pages of negatives, said Monisa Ahmed.

“They all felt it was inauthentic and deeply impersonal,” she said, particularly when it came to nuclear testing.

Though the Field hadn’t shied away from the subject — the U.S. detonated 67 bombs over the islands in the 1940s and ‘50s, rendering areas like the Bikini Atoll uninhabitable — the Marshallese felt the museum’s treatment was lacking in terms of how much displacement the blasts and subsequent fallout caused. And the human component was utterly absent.

“The students asked, ‘Where are the people affected by nuclear testing?’” Ahmed recalled.

The Field listened and acted on the complaints. Text was revised in several instances and the entire display surrounding nuclear testing was reworked to incorporate photographs of and quotes from Marshallese.

“That’s the new way of looking at exhibit production,” Ahmed said. “Knowledge is ever changing. When you make a mistake, correct it. If a museum isn’t going to listen to an Indigenous community, who is?”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]