Illinois’ much-ballyhooed attempts to attack climate change by moving to 100% clean energy within the next 29 years fizzled Tuesday, leaving uncertain the fate of the state’s burgeoning solar industry and thousands of jobs at nuclear plants Chicago-based Exelon is threatening to close come fall.

“We are disappointed that a comprehensive climate and energy bill that would preserve Illinois’ largest source of clean energy failed to pass, paradoxically putting at risk the clean air and jobs goals that all policymakers rightfully agree are critical to our state,” Exelon said in a statement Tuesday night. “Absent quick passage of legislation, Exelon has no choice but to proceed with retiring Byron in September and Dresden in November, as previously announced.”

Lawmakers couldn’t clinch a deal on a comprehensive energy package before their regular session ended in May, but were called back to Springfield on Tuesday for a special session to try again.

Instead, the Senate once again adjourned without taking action.

“We are this close to reaching that agreement, and I am confident that we will get it done,” Senate President Don Harmon said afterward at a press conference, as he pinched two fingers within an inch. “We came up a little short today, but we will get it done.”

Byron Nuclear Generating Station in Ogle County, Illinois. (Christopher Peterson / Wikimedia Commons)

Byron Nuclear Generating Station in Ogle County, Illinois. (Christopher Peterson / Wikimedia Commons)

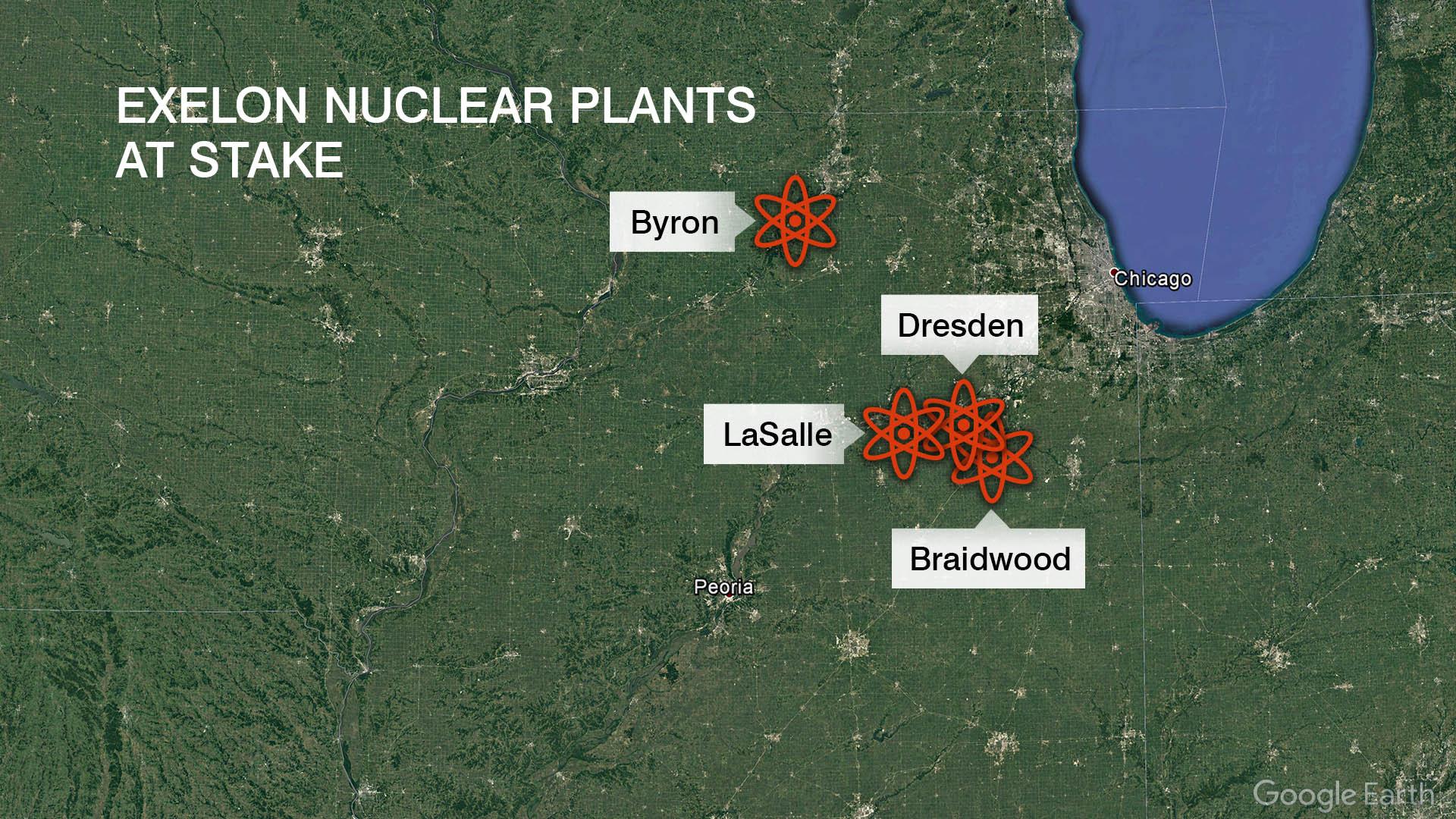

After more than a year of negotiations that ramped up in recent months, major tenets of the package appear set: electric ratepayers will pay $694 million over the next five years to Exelon in charge for keeping online the Braidwood, Byron, Dresden and LaSalle nuclear plants; state regulators on the Illinois Commerce Commission would regain more control over how much Exelon subsidiary Commonwealth Edison can charge customers for delivering electricity to their homes and businesses; the ICC would likewise be empowered to investigate if and how ratepayers were bilked in relation to a long-running bribery scheme that ComEd admitted to in federal court documents last summer.

But a standoff between two of Democrats’ biggest allies is preventing a deal, said Sen. Bill Cunningham, a Chicago Democrat who has led a legislative working group on energy issues.

“There’s a very simple explanation for why we’re here right now. Two of the most important Democratic constituency groups are in disagreement: environmental activist and organized labor,” he said. “That creates problems for Democratic legislators. The second we bridge that gap I think we’ll have a bill and I think we’ll have that bill before the summer’s up.”

Several legislators involved in energy talks told “Chicago Tonight” on Tuesday, just after it became clear that a consensus was out of reach, that they were likewise optimistic an omnibus package will move in the coming months.

“It needs to happen,” said Rep. Ann Williams, D-Chicago, a leader of the environmental caucus. “We are poised to pass one of the most nation-leading, comprehensive climate bills that’s been seen and it has to happen for climate, for jobs, for recovery from COVID.”

Sen. Michael Hastings, D-Tinley Park, said while there are “hang-ups” he’s hopeful an agreement will be reached in the next several weeks that will “make one of the largest investments not only in renewable infrastructure here in Illinois but saving tens of thousands of jobs across the state as well.”

Video: Watch part two of our roundtable discussion with lawmakers.

But with a compromise so far elusive, there’s a blame game of finger-pointing over who’s at fault – the governor? Harmon? — and swirling assertions of key interests moving their goal posts.

The Illinois Clean Jobs Council, an organization composed of 200 member groups including the Illinois Environmental Council, NRDC, League of Women Voters and the Chicago Teachers Union, released a statement Tuesday that seemed to pin the impasse on Harmon, while applauding Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s efforts.

“On May 31, there was a tentative deal on a comprehensive energy bill, but it was stopped at the last minute. On June 1, Senate President Harmon said he ‘stand[s] with the Governor on de-carbonization targets that need to be in a final deal,’ but now the Senate is headed home without action on that plan,” the statement reads. “Thousands of union workers and solar installers may now lose their jobs, while the climate crisis worsens and Black and Brown communities continue to struggle. We are deeply disappointed the Senate adjourned without taking action on a carbon-free energy future, but stand ready to enact the Governor’s plan as soon as possible.”

Meanwhile, union leaders huffed behind the scenes with frustration at the governor.

State Sen. Sue Rezin, R-Morris, whose district includes some of the nuclear plants at stake, blamed Pritzker for setting “unrealistic demands.”

“Proposals that would cost thousands of jobs and potentially increase our electric bills up to 20 percent, were the reason the Illinois Senate did not take a vote on any energy legislation. There simply was not enough support for the Governor’s plan, and he was not willing to negotiate with the unions,” Rezin said in a statement.

In written testimony for a Senate committee, Deputy Gov. Christian Mitchell said the administration had “moved substantially. The other side has not moved much.”

“Everything we were told was necessary for an agreement – including a carbon capture exemption that gives both the Governor and environmentalists heartburn – is now present,” Mitchell’s testimony reads. “And at some point a progressive climate bill is no longer a climate bill.”

Later in a statement, Pritzker’s press office said the administration had presented “a comprehensive energy package that makes substantial progress on climate change and preserves union jobs” that “doubles the state’s commitment to renewable energy, puts Illinois on a path to 100 percent clean power by 2050 … and would have made Illinois the best place in the country to manufacture an electric car. On top of all of these critical climate proposals, the bill leads with needed ethics and transparency reforms. The Senate chose not to take up that bill today.”

Rep. David Welter, R-Morris, whose district encompasses the Dresden, Braidwood and LaSalle nuclear plants, said that while Democrats are looking for GOP votes to support a package, his party has a different philosophy on how to get to a green energy future.

“A one-size-fits-all for Illinois is not going to work in this situation. What works in the PJM (a regional transmission organization that coordinates wholesale electricity movement) market in northern Illinois is not going to work in southern Illinois and that’s what I don’t believe we’re necessarily respecting or taking into account,” Welter said.

It was originally presumed that the Exelon subsidy – critics term it a “bailout” – would be the biggest hurdle, given that it would directly hit customers’ pocketbooks, Exelon and ComEd’s ignominious reputation at the statehouse, and a hundreds of millions of dollars chasm between the amount of financial assistance Exelon had originally wanted in exchange for not retiring the reactors and what Pritzker was willing to give.

Instead, widespread agreement that Illinois’ carbon-free future depends in the short term on nuclear energy coupled with Exelon’s weakened bargaining position due to the corruption scandal helped key stakeholders agree that ratepayers will see subsidies on their electric bills worth nearly $700 million over the next five years.

Still, the General Assembly’s inaction means several Exelon plants remain imperiled.

“We are mindful and appreciative of efforts by environmentalists and labor leaders to continue negotiating on the remaining issues and we hope that legislative leaders are right in expressing optimism that this stalemate may be resolved in time to preserve Illinois’ nuclear fleet,” Exelon said in its Tuesday night statement.

In recent weeks, how and when to phase out coal as a source of energy became the major sticking point.

Environmental advocates wanted a total ban on fossil fuels by the decade’s end, while operators of Springfield’s City Water, Light, and Power plant and the Prairie State Energy Campus (a coal-fired power station built near East St. Louis less than a decade ago, and which has contracts to provide power to several Chicago suburbs) argued that premature closures would be financially devastating for their respective municipalities.

That hurdle appeared to be breached, with a late-breaking compromise offer from Pritzker’s administration that would force most of Illinois’ existing coal plants to close by 2035 while the Prairie State and CWLP plants could stay open an extra 10 years if by 2034 they’re able to use developing sequestration technology to capture 90% of carbon emissions.

“I think everybody has digested the fact that coal is going to have to go offline in 2035 unless some significant technology improvements become available and affordable and I think people are coming to terms with that,” Harmon said. “Really the conversations over the last 36 hours have revolved around this newfound emphasis on the pace of decarbonization in the natural gas space.”

The holdup now, Harmon said, is over the elimination of another fossil fuel. Environmentalists want natural gas capped until it’d be gone in Illinois come 2045, a deadline that labor organizations contend is a job-killer.

Meanwhile, Illinois’ burgeoning solar industry is standing at a so-called cliff, as the lack of an omnibus energy law means structural and financial problems with an existing law meant to prop up renewable energy via state-backed credits remains unfixed.

Rep. Jason Plummer, R-Staunton, said he’s concerned that the legislation as proposed thus far will create a “new ethics nightmare in Springfield” because wind and solar energy companies would be in line for state assistance without enough checks.

Video: Part two of our roundtable with Illinois Sens. Michael Hastings and Jason Plummer; and state Reps. Ann Williams and David Welter.

Follow Amanda Vinicky on Twitter: @AmandaVinicky