Paul Eberhart, a lead animal care specialist at Brookfield Zoo, spends some time with the Nigerian dwarf goats. (Jim Schulz / Chicago Zoological Society

Paul Eberhart, a lead animal care specialist at Brookfield Zoo, spends some time with the Nigerian dwarf goats. (Jim Schulz / Chicago Zoological Society

Chicago’s museums have shut down twice now due to the coronavirus pandemic, bleeding revenue as they closed their doors to visitors in the spring before reopening with drastically reduced capacity in the summer and locking up again as COVID-19 cases spiked in the fall.

As a unique class of museum, the city’s zoos and aquariums have suffered along with their arts and culture counterparts, with one significant difference.

For institutions with “living collections,” the term “shutdown” is something of a misnomer. The thousands of animals at places like Brookfield Zoo and Lincoln Park Zoo, as well as the fish and mammals at the Shedd Aquarium, need to be fed and cared for, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, regardless of what’s going on in the human population.

Which means employee furloughs and budget tightening can only cut so deep.

“Every day we have to provide husbandry for animals. That can’t change,” said Bill Ziegler, senior vice president of animal programs at Brookfield Zoo. “We have been very, very efficient to keep operational costs down, but animals aren’t pieces of equipment you can park someplace and let sit there.”

There’s really no such thing as a low-maintenance animal, Ziegler added. While it’s true that every individual in a school of fish isn’t having one-on-one contact with a keeper in the same way as, say, a lion, there are filters, water heaters, aerators, lighting and food to consider.

“The reality is, every animal is taken care of every day,” he said.

It’s been a strain, said Andrea Densham, senior director of conservation policy and advocacy at the Shedd, which, in addition to its aquarium operations, has also maintained its conservation programs related to preserving aquatic habitat in the Midwest and Caribbean reefs.

“We can’t stop our mission-driven work. All of that work needs to continue,” Densham said. But at the same time, “70% of our budget is guests coming through the door. We lost $36 million. We need Congress to act, and we need that action to happen now. We love doing this work, but we need help.”

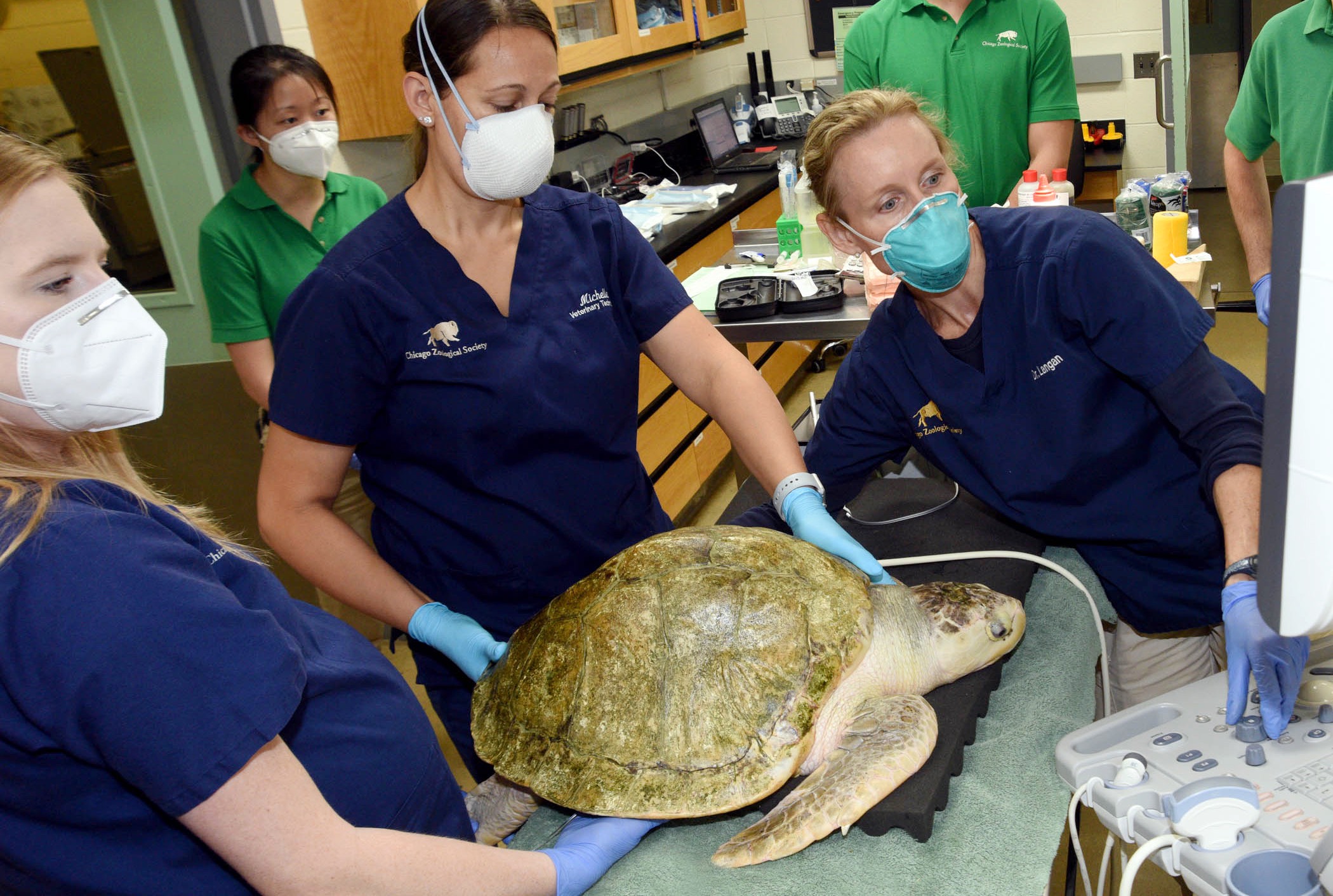

Pistachio, a 13-year-old Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, received a wellness exam by veterinary staff when he arrived at Brookfield Zoo in September. (Jim Schulz / Chicago Zoological Society)

Pistachio, a 13-year-old Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, received a wellness exam by veterinary staff when he arrived at Brookfield Zoo in September. (Jim Schulz / Chicago Zoological Society)

Though Densham is quick to draw a distinction between museums’ essential workers and the nation’s doctors, nurses and health care personnel — “Medical providers are doing heroes’ work,” she said — the fact remains that those involved in animal care, be it directly or indirectly, can’t perform their jobs remotely or press pause on their duties.

Approximately 100 people — animal care, facilities and security staff members — have been clocking in at the Shedd since the beginning of the pandemic. Dan Lorbeske, supervisor of fishes operations and leader of the galleries team, is one of them.

From a mental health standpoint, being able to maintain some semblance of his pre-pandemic routine has been helpful, Lorbeske said.

“For sure, it’s one of those things, to have some normalcy. I’m still going to work,” he said. “You still run into people and say, ‘Hi.’”

All of the Shedd’s safety precautions — including the installation of infrared thermometer stations — have made him feel comfortable about being in the building, Lorbeske said, and there’s even been an effort to inject a little humor into protocols like social distancing.

“We have signs that say things like, ‘Stay two penguin lengths apart,’” he said.

But there’s no getting around the changes COVID-19 has wrought.

Wearing masks all the time took some getting used to, particularly in trying to read people’s expressions with fewer visual cues, Lorbeske said. Once a bustling hub of activity and noise, the Shedd has become a cavernous echo chamber. “We only have people who need to be here. It’s a little (lonelier) for sure,” Lorbeske said.

Interaction is largely discouraged, and to promote social distancing, staff schedules have been staggered, including breaks. Meetings among colleagues are all but non-existent, either taking place virtually or confined to two or three people gathering in large conference areas meant to hold dozens. Even animal exams that might previously have drawn an audience of curious keepers keen to learn more about a species are now limited to those whose presence is absolutely necessary.

But it’s the lack of volunteers, who’ve been cut back to a minimum, that’s perhaps been most noticeable, said Lorbeske.

His team relied on volunteers to pitch in with food prep and four daily dives involving feeding and cleaning. Aquarium tank windows constantly need scrubbing to control algae, Lorbeske explained.

It’s been challenging to accomplish the same amount of work with fewer people but his team eventually got into a groove, he said. (And they turned down the lights in the aquarium, which has stunted algal growth.) Not having to tick off a laundry list of tasks before the Shedd opens for guests has helped, giving staff greater flexibility at least with the timing of certain responsibilities.

Still Lorbeske would rather be racing around like mad in the morning, prepping for crowds.

“One of the things I’ve missed the most is to go out into the public area and see the little kids stand in front of the fish and lose their minds,” he said.

Chow time. Animals need to eat, whether Lincoln Park Zoo is welcoming visitors or not. (Courtesy of Lincoln Park Zoo)

Chow time. Animals need to eat, whether Lincoln Park Zoo is welcoming visitors or not. (Courtesy of Lincoln Park Zoo)

Lorbeske’s experience was echoed by his counterparts at Brookfield and Lincoln Park zoos, where 125 and 75 employees, respectively, have remained engaged in various components of animal care throughout the pandemic.

Both zoos reconfigured staffing, particularly in the spring, to avoid overlap as much as possible and have relied on Zoom meetings when possible.

“That has created some feelings of disconnect. Our animal care staff, they’re by themselves. There’s some feelings of isolation,” said Ziegler, of Brookfield Zoo. “It’s just quiet out there.”

Dave Bernier, general curator at Lincoln Park Zoo, shared that sentiment.

“I love it when the zoo is full. It comes to life and that just didn’t happen this year,” Bernier said.

Given their vast outdoor acreage, the zoos were eventually able to welcome back guests on a limited basis in mid-summer, implementing timed ticketed reservations.

“We’ve actually seen good numbers,” said Ziegler. “People were tired of being cooped up. When we first reopened July 1, most of the comments were ‘Oh my god, it’s so good to get outside.’ I have yet to see a day, regardless of the weather, that people have not come to the zoo.”

But opening up the gates brought with it concerns about the added risk of coronavirus exposure, both to and from the public.

Lincoln Park Zoo bumped up its use of personal protective equipment more than it already had, mandating mask usage at all times among staff. After a tiger at the Bronx Zoo contracted COVID-19, staff began wearing masks even when alone with animals. (Masks, gloves and face shields have always been required among those working with apes, Bernier said. Since humans and primates can share diseases, staff at both zoos are required to wear PPE around primates.)

“All of us were worried about visitors,” said Bernier. “We waited for the shoe to drop and it never did. Nothing bad happened.”

Though institutions can take all the precautions in the world within their walls — PPE, hand washing, sanitizing surfaces and social distancing — they can’t control what happens off-site. Credit goes to staff at the zoos and aquarium for putting the animals first, administrators said.

“What we were worried about the most was what people do at home. ‘Where did you go for Thanksgiving?’ Every one of us paid attention to the scientists. They knew if one person gets sick, who’s going to take care of the animals?” Ziegler said. “These people are so dedicated.”

Bernier similarly tipped his hat to the conscientiousness of Lincoln Park’s staff off duty.

“People are clearly taking this seriously when they leave,” he said. “We’ve had no spread at the zoo.”

Andy Ferris, a senior animal care specialist, during a husbandry session with one of Brookfield Zoo’s bottlenose dolphins. (Jim Schulz / Chicago Zoological Society)

Andy Ferris, a senior animal care specialist, during a husbandry session with one of Brookfield Zoo’s bottlenose dolphins. (Jim Schulz / Chicago Zoological Society)

Staff have missed the opportunity to interact with guests in person and to talk about animals and conservation programs, but institutions quickly ramped up virtual programming to fill the void.

“One of the interesting things about this moment is that it allowed us to pull back the curtain and show what we do in a different way. With our success on social media, we’ve been able to share some of these stories about recent research and our habitat work,” said the Shedd’s Densham.

The Shedd’s penguins, sent around town on field trips, have been become viral sensations, doubling the aquarium’s Twitter and Instagram audience and growing its Facebook following by 30%, according to spokesman Johnny Ford.

“The penguins are very entertaining and fun, but to grow our audience means that for our urgent messages, our action items, we now have a larger number of advocates,” he said.

Brookfield’s “Zoo to You” videos have been so well received, and they’re likely to continue even when things return to normal, Ziegler said.

“It’s been a forced learning, but we’ve learned how to do it better,” he said.

Among the benefits of online programming, Ziegler said, has been the zoo’s ability to connect with people in the community for whom admission fees or transportation access have been a barrier.

But there’s no substitute for personal interactions, everyone emphasized. Now, as vaccines are being rolled out in Illinois, institutions can at least begin thinking about what post-pandemic operations will look like, though exactly when that moment will come remains a huge question.

“I’m going to be optimistic and say before the end of 2021,” said Ziegler.

And if that’s not the case? “You adjust,” he said, in what’s become the mantra of 2020. “You have to adjust.”

THE SOUND OF SILENCE

(Courtesy of Lincoln Park Zoo)

So how did the animals respond to the lack of visitors? Sorry folks, but they didn’t really miss us.

(Courtesy of Lincoln Park Zoo)

So how did the animals respond to the lack of visitors? Sorry folks, but they didn’t really miss us.

While shut down, Dave Bernier said the macaques would maybe look his way as he strolled through Lincoln Park Zoo, otherwise his presence was largely ignored.

The zoo’s pygmy hippos may even have benefited from the added privacy. Staff hadn’t previously seen much interest between its male and female pair in terms of breeding potential, but something sparked between the two over the summer, Bernier said.

“We’ve done a few ‘introductions,’” he said.

At the Shedd Aquarium, Dan Lorbeske said he noticed that some of the small schooling fish grew more skittish around humans as the shutdown lengthened. He surmised that the previously steady flow of people had become a sort of “white noise” for the fish, and then in the sudden absence of crowds, the occasional appearance of a passing staff person was more startling.

One exception to the “I want to be left alone” rule was the Shedd’s giant Pacific octopus, said Lorbeske.

The creature became more withdrawn and less active, prompting the creation of a timed schedule for staff to swing by and stand in front of the octopus, just to give him something to look at, Lorbeske said.

Who knew? Man, the octopus’ best friend.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]