(Photo by Andrew Ebrahim on Unsplash)

(Photo by Andrew Ebrahim on Unsplash)

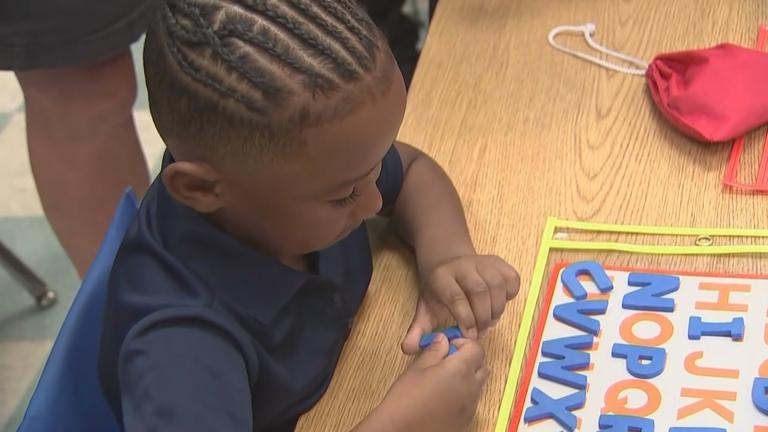

Despite a cultural tradition of using family members, friends or neighbors for early childhood care, many Latino parents want to enroll their preschool-aged children in formal child care centers, but are stymied by shortages of child care centers in majority Latino communities, among other factors, a new study finds.

After interviewing Latino parents in two Latino-majority neighborhoods, the study by the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration and Chapin Hall recommends ways for community members, policymakers, child care providers and others to increase Latino families’ access to formal early childhood care.

The study, which was completed before the coronavirus pandemic, notes that differences in the use of formal childhood care by race or ethnicity are narrowing, perhaps because of recent investments in public preschool in some predominantly Latino communities.

In addition, the city of Chicago has made increasing enrollment in high-quality child care and early childhood education a priority, which is one reason why researchers said it’s important to better understand how Latino parents make child care decisions.

Even though the city has recently expanded early learning and care opportunities, investments in formal child care, such as licensed center-based programs and licensed family child care homes, remain uneven geographically and across racial and ethnic groups, researchers said.

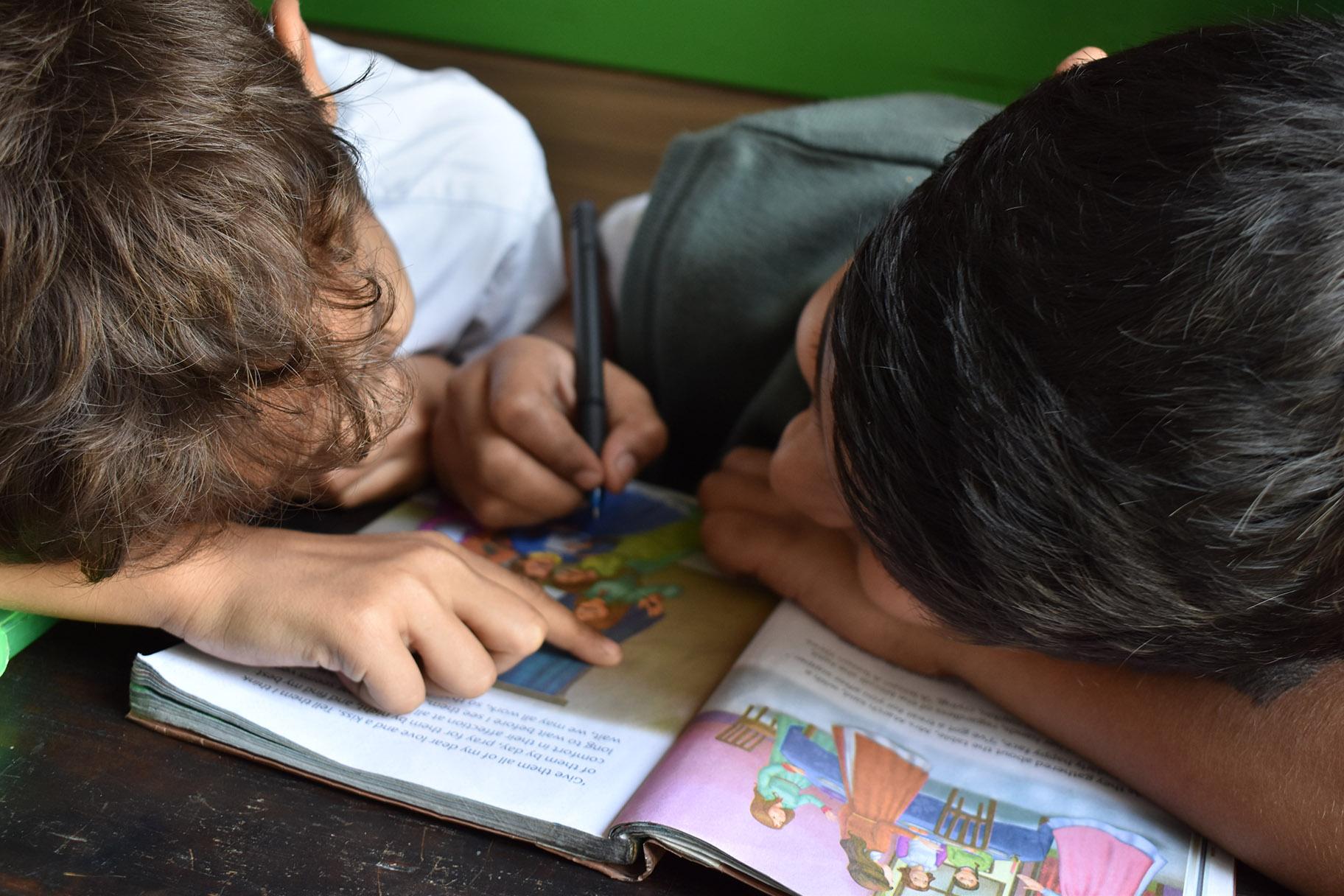

The study focuses on two primarily Latino neighborhoods in Chicago: Belmont Cragin on the Northwest Side, and Little Village on the Southwest Side.

Researchers interviewed eight directors of child care centers about such topics as the availability of care in the neighborhoods and the opportunities and challenges that parents face in accessing child care.

They also conducted in-depth interviews with 32 Latina mothers who have at least one child under age 5.

While Belmont Cragin has more childhood care centers, both neighborhoods qualify as child care deserts—defined as a zip code with at least 30 children under the age of 5 and either no child care centers or so few that there are more than three times as many children under age 5 as there are spaces in the center.

Mothers in the sample had a total of 42 children that were 5 years and under, with 22 living in Little Village and 20 living in Belmont Cragin.

Mothers in both communities perceived a limited supply of child care options. Although Belmont Cragin has many more licensed child care centers and homes, the study found that families in both communities appeared to lack information to help them understand the different types of child care arrangements available.

Mothers in both neighborhoods cited similar barriers to enrolling their children in child care programs including programs being at capacity and having long waitlists, hourly work requirements to qualify for subsidies, and administrative burdens such as paperwork.

Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood is described as a child care desert in a new University of Chicago study. (WTTW News)

Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood is described as a child care desert in a new University of Chicago study. (WTTW News)

Mothers said they needed more access to information about child care options.

“Especially with the Spanish-speaking community because they think that they don’t have it and with the government whole thing, they’re scared and that makes it hard. So, if anything, what we lack is communication,” said one mother in the study.

Participants said their child care decisions were based on multiple factors including convenience, proximity, affordability, family schedules, the child’s well-being, safety and feeling trust for the child care provider, being able to have multiple children at one site, and having a provider that would support a child’s development or other needs.

While acknowledging that increasing access to childhood care is a complex problem, researchers came up with recommendations for increasing Latinos’ access to childhood care.

Some of the recommendations are:

—Revise Illinois Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) subsidy income eligibility threshold for two-parent households. Both center directors and parents expressed the belief that many two-parent families are not eligible for child care subsidies because of income rules for two-parent households. Families with two working parents sometimes earned too much money to be eligible, but the high cost of care made child care inaccessible. Increasing the income eligibility threshold for two-parent households may also lead to greater use of child care programs.

—Encourage child care providers to increase the number of slots for infants and toddlers and increase public support for this care. Child care center directors reported having difficulty filling available slots because of competition from Chicago Pubic Schools pre-K programs. They didn’t have this difficulty with infant and toddler slots because CPS pre-K does not offer care for these age groups. Despite clear demand, caring for infants and toddlers is more expensive because of stricter requirements for child-teacher ratios. Researchers said increasing public support for infant/toddler child care is critical and could be achieved through such mechanisms as enhanced payment rates, bonuses, and infrastructure grants to incentivize expansion of dedicated slots for infants and toddlers.

—Relax identification requirements to access care. Some participants mentioned that paperwork and identification requirements posed barriers to enrollment in formal child care arrangements. Considering policies that would soften these requirements may alleviate some of the administrative burdens for parents, reducing barriers to formal child care enrollment.

—Increase supply of formal child care and early education options in communities. Although researchers did not observe differences in knowledge, access, or use of child care options between Belmont Cragin and Little Village participants, they said there is an urgent need for more options in both communities that are tailored to families’ needs and preferences. Participants identified a high need for programs that serve multiple children of diverse ages, more options for infant care, and low-cost arrangements at unique and diverse sites such as ESL locations.

Some of the study’s other recommendations include maintaining bilingual directories outlining child care options within communities, promoting the hiring of child care workers within neighborhoods to alleviate some concerns about safety, disseminating information about subsidies that help offset the cost of care, and encouraging child care providers to hold open houses to build trust, get to know families and identify safety features such as video cameras.

Annemarie Mannion is a freelance contributor to WTTW News.